Pesky flying insects around horse properties are just that … pesky. However, insects can be much more than simple annoyances; they can also spread serious and even fatal pathogens, causing diseases in horses as well as their humans. Horses can become hosts for arthropod-borne diseases such as West Nile virus, equine infectious anemia, Lyme disease, and pigeon fever. Filth flies can transport viruses and bacteria such as Salmonella, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus (commonly called staph), and Escherichia coli.

“Actually, insects and other arthropods don’t transmit diseases,” in the classic sense by becoming infected with the pathogen (disease-causing agent) itself and then shedding it and infecting others, explains Dr. Erika Machtinger, a veterinary entomologist with Pennsylvania State University Extension and a lifetime horse owner. “They carry pathogens that cause disease.”

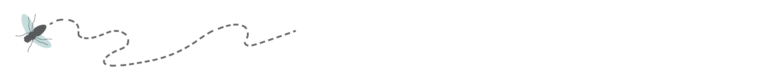

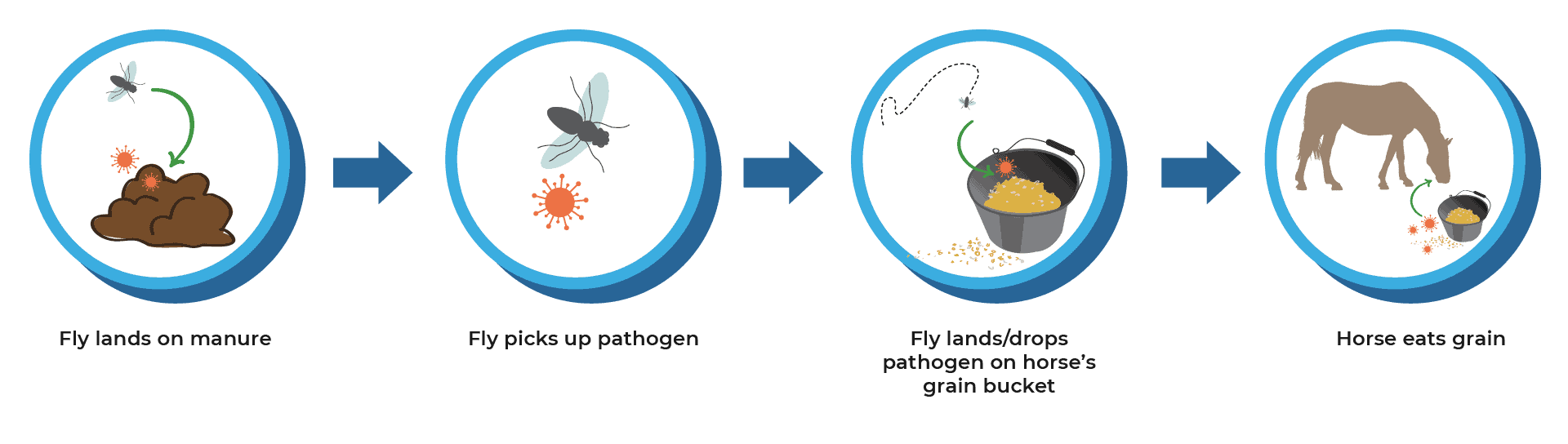

There are two primary ways arthropods can spread pathogens: mechanically and biologically. “Mechanically is like when a fly lands on manure, picks up E. coli, and then drops it on your turkey sandwich,” she says. “The fly doesn’t have a biological relationship with that pathogen, but it is moving it from one place to another. Biologically transmitted pathogens are those that have an intimate relationship with the arthropod. For example, when the malaria pathogen is picked up by blood-feeding mosquitoes, it develops through some portion of its life cycle within the mosquito. In other words, often biologically transmitted pathogens require a certain vector to complete their movement from one host to another.”

Erika Machtinger,

MS, PhD, CWB

Machtinger is a veterinary entomologist with Pennsylvania State University Extension, in State College, where she deals with nonhuman pests and invertebrates, working with stakeholders and as a team lead for the vector board. She is the author of several books, including Pests and Parasites in Horses, a 400-page publication for horse owners that includes information on how to identify insects so you can choose the optimal control method(s) and even how to properly fit a fly sheet—using her home-bred dressage mare as her demo guinea pig.

Example of Mechanical Transmission

Example of Biological Transmission

Insects can bother horses and livestock to the extent that they develop leg or hoof injuries from stomping or lose weight from stress. In extreme infestations animals might seek shelter in ponds or by rolling in mud. (In fact, many horses roll in mud even with lower fly burdens, and ponds and mud can cause fly populations to thrive and multiply—more on this in a moment.) Continued exposure to insects can cause a horse to develop insect bite hypersensitivity, usually attributed to a combination of genetics and allergic triggers. Some itchy horses rub, scratch, or bite themselves to the point their skin is damaged, inflamed, and infected and they experience hair loss around the mane, tail, and across the body.

PHOTO: Getty Images

Eliminating Flies, Mosquitoes, Midges

A successful insect control program is multitiered, targeting different life cycle stages, and combines various methods, beginning with the least toxic tools and moving on to the bigger hammers as situations become more challenging. To launch an insect control program, you must first understand the pests on your property and their life cycles and habitat needs. Take, for example, the ubiquitous fly.

“Start by identifying the specific fly or other pests on your premises,” says Machtinger. For fly control, she suggests trapping flies and sending them to your state extension office for identification. Or you can take photos and describe their behavior and share that information with your extension entomologist.

“There are primarily four species of flies that are horse pests that horse owners may see regularly,” she says, all considered filth flies. “Houseflies and stable flies develop in any (kind of) manure or decomposing organic material. If there are many flies in the barn, they are houseflies. Stable flies do not like to venture into barns.”

Stable flies are the biting flies that “prefer to feed from the legs, which is why they cause stomping, but they will land on other areas, too (like the belly or chest),” Machtinger adds. The other two most common filth flies are horn flies and face flies, which only develop in cattle manure and are pasture pests. Face flies congregate around eyes and noses, sometimes nearly covering a horse’s face.

Housefly

Stable Fly

Horn Fly

Face Fly

Mosquito

Biting Midge

Other flying insects—namely mosquitoes and midges (often called no-see-ums)—can be quite fierce in some parts of the country.

“We especially worry about mosquitoes and midges because they transmit a number of viral pathogens,” says Dr. Cassandra Olds, a veterinary entomologist and an assistant professor at Kansas State University, where she is researching and teaching animal health entomology. She is also a horse owner, getting firsthand experience with pest control, and notes that five-way equine vaccines protect against most pathogens these insects transmit.

She encourages horse owners to vaccinate at the right time of year, in spring before mosquitoes come out. “We have to do this every year because it’s expensive (energywise) for the body to make antibodies, so the body eventually quits making them without regular boosting,” Olds says. “We can lose horses to these viruses pretty easily (if we don’t vaccinate).”

Biting midges are blood feeders that can be problematic for horses. “They are very small, which is part of the problem,” she says. “You can’t see the larvae, they are microscopic. Adults look like tiny mosquitoes, but much smaller. They bite horses on the muzzle or other areas where the skin is thin. They are often dawn and dusk feeders. Typical location habitats for midges are along edges of ponds, leaking water troughs, and puddles of water, especially in areas contaminated with animal waste.”

Cassandra Olds,

MS, PhD

Olds is a veterinary entomologist at Kansas State University, in Manhattan. Her research focuses on understanding the relationships between animals, insect pests, and the pathogens they transmit. Ongoing research in her lab focuses on reducing fly worry in horses and communicating best practices to horse owners. She owns an 18-year-old buckskin mixed-breed gelding named Tell.

Insect control for any of these species falls into four categories:

CULTURAL METHODS

(cleaning up manure, performing mud

and drainage management)

MECHANICAL METHODS

(fly swatters, fly masks,

fly sheets, fly tape, fans)

BIOLOGICAL CONTROLS

(employing organisms that are

natural enemies of the pest)

CHEMICAL CONTROLS

(fly repellent,

insecticides, feedthroughs)

PHOTO: Getty Images

Cultural Insect Control Methods

All filth flies are very manageable when you can reduce habitats where they develop and, thus, the number of hatching adults. “Routine manure management is the best way to do this,” says Machtinger. “Flies develop in four to six days, based on available nutrients and temperature, which is a really quick time.” This can stretch out to a couple of weeks in cooler climates.

Olds recommends implementing as many cultural controls as possible to reduce mosquito and midge populations. In particular, keep water tanks clean. “Even in small automatic waterers, if it’s clean water, the mosquitoes struggle to find food to eat. If there’s organic particulate matter, then they can eat and thrive.”

Another cultural control Olds recommends for midges—which can also help with stable and houseflies—is mud management. “Stable flies really like mud and decaying organic matter like hay,” she says. “Over the winter horse owners (often) feed from big round bales. In the (hay) waste around it we find pupae and larvae of stable flies.”

Keeping horse confinement areas clean and well-drained and picking up manure are paramount. “It’s when manure is wet that it becomes a problem and habitat for (the development) of more insects,” says Olds. “They need it wet. You can have piles of dry manure and it’s not a problem, because it’s not a habitat for flies.” If horses are standing in mud from playing in a stock tank, for instance, “it is an insect’s happy place. Anywhere there’s substrate they like, (insects) will live.” Even hoofprints holding water can become mosquito habitats. (See sidebar on mud management.)

Reduce horses’ midge exposure by keeping them inside the barn during the times of day when insects are present, she adds.

“This will also help for reducing exposure to mosquitoes,” says Olds, although some types of mosquitoes can change their behavior based on the host’s behavior, such as traveling into a building to seek out a meal.

Mud Management Tips to Reduce Insect Habitats

Mud is a breeding ground for insects, especially biting midges and filth flies. It’s also inconvenient, unpleasant, and can pose health risks. To minimize areas that can become natural pest habitats, follow these steps for addressing mud problems on your horse property:

- Create a confinement or heavy-use area to be used regularly to keep pastures from becoming overgrazed and muddy, particularly during winter.

- Remove manure from confinement and high-traffic areas every one to three days.

- Tarp the manure pile.

- Improve drainage.

- Fix leaks in water lines and stock watering tanks and mend or eliminate leaky hoses.

- Install rain gutters and roof runoff systems on all barns, sheds, and outbuildings to divert clean rainwater away from high-traffic areas.

- Dump, scrub, and refill all stock tanks at least once each week.

- Check for containers and other places where water can collect.

- Plant and maintain native trees and shrubs.

Eliminating standing water and reducing mud on your horse farm will substantially decrease the noxious insect population. As a bonus, it will make your property more chore-efficient and attractive.

PHOTO: Courtesy Weatherbeeta

Mechanical Controls for Flies on Horse Farms

If you board your horse or have neighbors that don’t practice good manure management, you must resort to other control methods, such as fly bags, traps, and wearable gear.

“Fly bags have a purpose, but they aren’t a (total) control,” Machtinger says. “Fly bags only trap houseflies and might also trap beneficial insects. Plus, people often don’t use them correctly; they hang them out until they are so full that they are creating an opportunity where flies can breed.”

Replace fly bags at least weekly. “Placement is also important,” she adds. “Have fly bags in a warm area where they intercept (flies coming from other) livestock properties or in locations lacking manure management.”

There are no effective traps for horn and face flies, because they only rest on the animal. “(These flies) are going for mucosal secretions on the eyes, mouth, and nose of a horse,” says Machtinger. The only way to manage them is with on-horse management—mechanical barriers such as masks, sheets, and fly boots—or repellents.

“Masks, sheets, and fly boots (are) physical exclusion devices used to create a layer between horse and fly that are also useful for many other types of pests (such as mosquitoes or midges), so there’s more bang for the buck,” she says. Machtinger’s personal recommendation is to use zebra-striped fly sheets and masks, because scientists are learning a zebra’s stripes might confuse and repel flies. “(This) gives extra protection against horseflies and stable flies—and pretty much all flies.”

She cautions, however, that other horses might spook at pasturemates wearing zebra-striped fly sheets when you first introduce them.

When fitting a fly sheet (see sidebar for tips), you can choose from many varieties and fits. “You want a fly sheet with good airflow,” says Machtinger. Fly sheets designed to protect from biting midges, which can cause the reaction referred to as sweet itch, are more snug and protect the horse better from these pests.

Olds says fly wraps also work well for controlling stable flies. These cover lower legs, which is the fly’s preferred area for feeding. “During fly season farriers will notice a lot of cracked hooves from stomping,” she says. “Horse caregivers often underestimate the problem; flies feed once and go off to rest, so every fly that you see is a new one. When I talk with horse owners, I explain how a lot of studies show that (any kind of) constant chronic stress makes your immune system stressed, leaving an individual susceptible to other stress factors. Eventually something has to give.”

Manufacturers are also developing gear treated with insect repellent. The pyrethrin binds to fibers in the cloth, making it safe even around cats (pyrethrins are toxic to cats), and it doesn’t wash off. “You cannot treat horse gear yourself,” says Machtinger. “But if you have a fly sheet that you love and you want to have it treated, there are companies that do this.” Bonus: Treated fly sheets also repel mosquitoes, and they might even work to repel ticks, she adds.

Lastly, fans can serve as additional mechanical control options, particularly against midges, which are weak flyers.

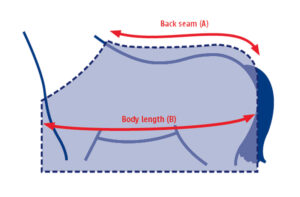

Fly Sheet Buying and Fitting Tips

Fly sheets come in many designs and materials. Whether you want a soft, clothlike sheet, one that also offers UV protection from the sun, or one that will survive pasture playtime, use these tips to aid in your fly sheet selection and fitting process:

- Measure your horse to determine his size. Using a weight or measuring tape with inches, place one end mid-chest, at the base of the neck, and measure around the body to the center of the tail. The number of inches is his sheet size.

- Most protective equipment is designed to deter a specific insect pest, so identify which insects are problematic for your horse and shop for a sheet that will protect against them.

- Consider choosing a zebra-striped sheet for protection against horse- and deerflies.

- Consider fly sheets with extended necks, detachable hoods, or belly bands for extra coverage.

- Ensure all protective equipment fits your horse comfortably and does not rub or chafe—nylon linings can help prevent this.

- Fly sheets can come with darts, pleats, or gussets, each of which allows for better movement.

- Boots and masks are usually sized by horse type (e.g., pony, cob, warmblood).

- Durability is one of the most important qualities to consider with boots and masks.

- Breathability is another important consideration, particularly for humid climates. The smaller the mesh, the less airflow it has. Polyester materials might offer more breathability.

- Breathability for fly boots is important to reduce heat stress on leg soft tissues.

- While horses can wear protective gear all day, observe them on hot days to ensure they’re not overheating.

Check your horse’s fly sheet regularly to ensure it still fits well, and remember that one manufacturer’s design might fit a horse’s build and body type better than another company’s model.

PHOTO: Getty Images

Biological Controls for Flies

Biological approaches—fighting nature with nature–might be gentler on the ecosystem, easier to use, and more cost-effective than chemical and other options.

Birds

Encourage insect-eating birds, such as violet-green swallows, tree swallows, barn swallows, bluebirds, purple martins, and cliff swallows, to move into your yard and barn area. Members of the swallow family can be tremendous assets to a horse facility as they dive and dart through the neighborhood collecting bugs.

Bats

These creatures play an important part in every healthy environment, eating thousands of mosquitoes and other agricultural pests per night, says Olds.

Encourage a bat family to move onto your property by hanging a bat box built specifically for the types of bats in your region. Place bat houses on the southern exposure of a barn, pole, tree, or house. The best habitat is within a half mile of a stream, lake, or wetland. Install bat houses by early April and be patient because it might take up to two years for a colony to find them.

A word of caution: Because bats can carry rabies, make sure your horses are up to date on their core vaccinations. And always leave bats alone. They are not aggressive but, like any wild animal, they might bite to defend themselves if handled.

Did You Know?

SOME BATS CAN EAT UP TO 1,000 MOSQUITOES PER HOUR.

1 ADULT BARN SWALLOW CAN CONSUME THOUSANDS OF INSECTS PER DAY, A NUMBER COMPARABLE TO A BUG ZAPPER.

Good Bugs

One example of a beneficial insect horse owners can put to work is a fly parasitoid—a gnat-sized nocturnal wasp that lays its eggs in developing fly pupae, thereby reducing the fly population. They do not harm humans or animals and are rarely even noticeable because they are tiny and only active at night.

“There are a couple of different naturally occurring species that vary by region,” says Machtinger, noting it’s important to release a product containing a mix of species so you end up with parasitoids suitable for equine facilities as well as for cattle. The key point to keep in mind is the life cycle for parasitoids is three weeks.

“If you only release monthly, they are not going to keep up with the fly’s short reproductive life cycle,” she says. For effective fly control, release parasitoids early in the fly season and again every two weeks in and near the barn.

PHOTO: Getty Images

Chemical Insect Controls

Last on the list of tools for fly control are the big hammers: chemicals. With any pesticide or chemical insecticide, Machtinger emphasizes “the label is the law,” meaning the EPA has deemed a product has a low risk of toxicity only when used according to the directions on the label.

Direct application fly sprays—nearly all of which contain a pyrethroid (a synthetic insecticide)—are popular among horse owners.

“People use fly sprays a lot and have been using them for a long time, so we are getting resistance in insect species,” says Olds. In one study she found most fly sprays wear off in a matter of hours, after which the horse gets recolonized with more flies. Her concern with using fly sprays is “the fly is only sitting on the horse for two minutes, and (by doing so) it gets a microdose of chemicals, which then increases resistance.”

For this reason natural fly repellents that contain ingredients such as oils or fatty acids are gaining in popularity.

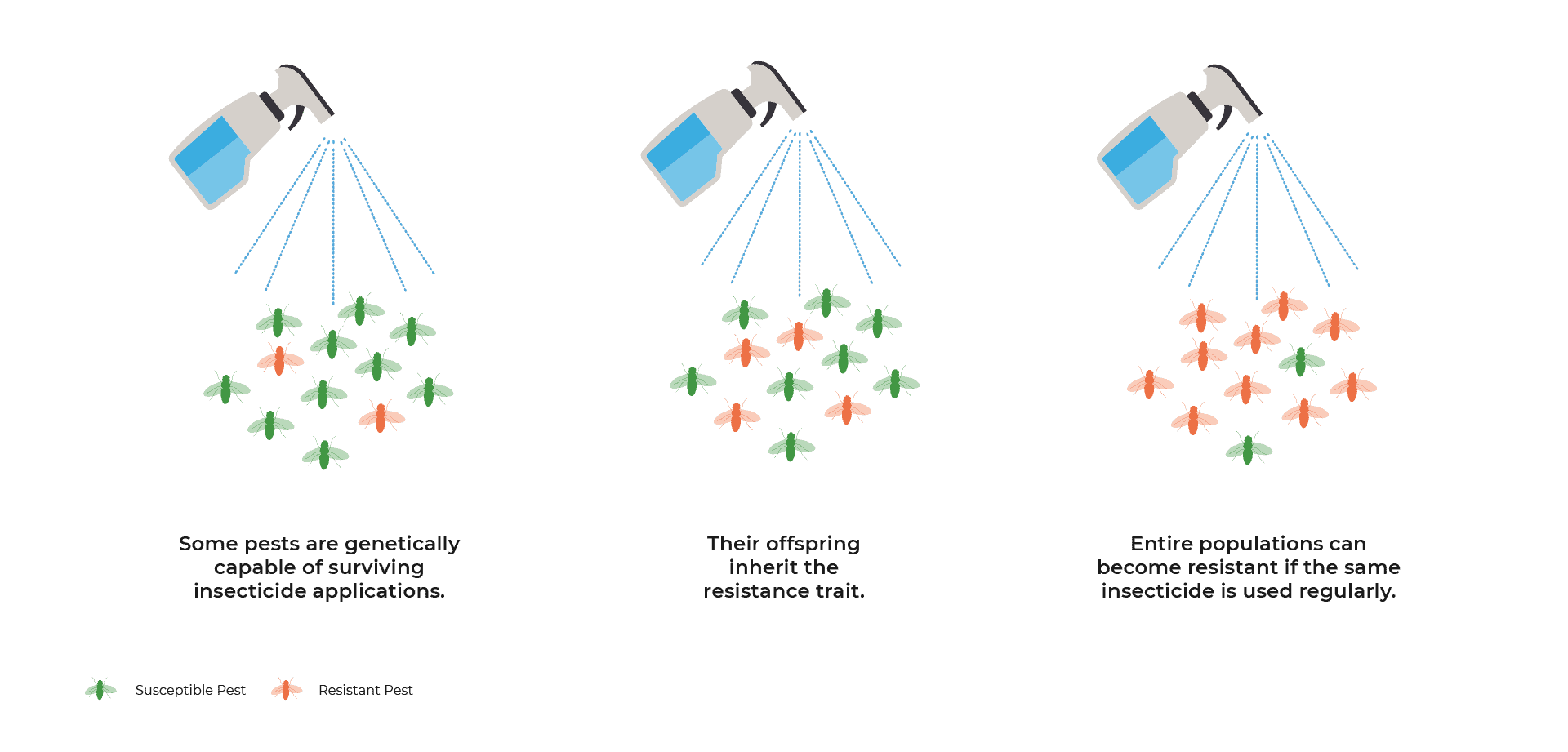

Some pests are genetically capable of surviving insecticide applications. Their offspring inherit the resistance trait. Entire populations can become resistant if the same insecticide is used regularly.

Fly baits, which combine an attractant and a food source (usually sugar) with a pesticide, only work against houseflies, says Machtinger. Again, follow the label so you are deploying them safely.

Feedthroughs are chemical compound controls that act on fly development. “The fly (both stable and house) in the manure digests it,” she says. Every single horse on a property must be on this product for it to work, but “you don’t need to feed it when flies aren’t a problem—or if you are composting manure (not stockpiling it).”

“(Feedthroughs) are safe to use,” says Machtinger, “because the growth regulator for flies won’t affect anything else. It is very specific to the order of flies that is a pest for us.” However, because of the fly’s short life cycle, it can quickly develop resistance to the chemical in a feedthrough product. “If you are implementing this protocol, you need to rotate every month between the three different products on the market,” says Machtinger. “This approach fails if you use the same thing over and over.”

Residuals are insecticides that work well when applied to areas where flies routinely land—such as on a sunny wall—and can pick up the pesticides. “Historically,” says Machtinger, “residual pesticide spray application to stable or barn surfaces has been one of the more popular fly control strategies. As a result, high levels of pesticide resistance to active ingredients in these products are now common. Residual pesticide application should be used sparingly and only as a last resort to control fly outbreaks that cannot be managed with other control tools. If residual pesticide spray use does not reduce the fly population after application, either the pest species has been misidentified or the fly population is resistant to the active ingredient being used, and it should not be reapplied.”

Additionally, Machtinger says residual insecticide might impact nontargeted beneficial arthropods that encounter it.

She also discourages the use of automatic spray systems. “When sprays go off, auto systems are only knocking down adults, which creates resistance (in the flies). Plus, all the humans and animals in the barn are breathing this in, and that’s a concern.”

PHOTO: Getty Images

Take-Home Message

To sum things up, control insect pests on horse properties by identifying the species and knowing their behavior and habitat. Then launch an array of management techniques that target different stages of the insects’ life cycle. Begin with the least-toxic cultural, mechanical, and biological controls, and save chemical controls for serious infestations. “I always recommend an integrated approach” says Machtinger. “Sanitation and composting or manure management are key. Then (use fly) traps depending on the species, and use biological controls, the parasitoids.”

Put insect-eating birds and bats to work on your property, and use mechanical controls such as fly masks and sheets, as well as fans.

With these items in your toolbox, you’ll have more options available for dominating the bugs in the coming insect season. You and your horse don’t have to put up with all the pesky pests, and you’ll be safer with less chemical use on your horse property.

Sponsor’s Message

For over 40 years WeatherBeeta has embarked on a brand mission to create high-quality, comfortable, innovative, and durable protection for horses.

This summer you can protect your horse with a WeatherBeeta Fly Sheet that is designed with Comfort and Fit in mind. The WeatherBeeta Fly Sheet range offers protection for your horses from flies and insects as well as UV rays. With a variety of different fabrics and features, you are sure to find the perfect style to suit you and your horse’s needs.

The WeatherBeeta ComFiTec Ripshield Plus With Belly Wrap is a popular choice for the blanket wrecker, made from a strong and durable fine mesh with a 1,200-denier polyester cross hatch, which helps limit tears.

A classic style at a great price with a soft and durable mesh that offers over 65% UV protection, the WeatherBeeta ComFiTec Essential Mesh II is a great choice, with the option to spice up your horse’s wardrobe being available this season in the Seahorse Print and Diamond Navajo Print/Black.

The sensitive horse that suffers from irritation and skin allergies from biting insects or UV rays would be more suited to the WeatherBeeta ComFiTec Sweet Itch Shield Combo Neck. This style offers head-to-tail protection featuring a stretch panel that extends over the ears from the poll and a full wrap tail flap and belly wrap, as well as over 90% UV block.

Summer sheets are super alternatives to the traditional mesh style fly sheet. Designed to be worn in the paddock when the weather is warm, a summer sheet will protect your horse from the sun and prevent their coat from being bleached by harmful UV rays, while still remaining lightweight and highly breathable. The WeatherBeeta Breeze With Surcingle IV Combo Neck is a perfect choice.

Protect your horse’s face and eyes from the sun and insects with a WeatherBeeta Fly Mask. The range of masks has been designed with comfort and fit in mind and offers the ultimate in protection without impacting vision.

The WeatherBeeta brand has a reputation around the world for design in comfort, fit, and quality, making it an ideal choice for anyone who wants to protect their horse from insects this summer.

Credits

Alayne Blickle, a lifelong equestrian and ranch riding competitor, is the creator/director of Horses for Clean Water, an award-winning, internationally acclaimed environmental education program for horse owners. Well-known for her enthusiastic, down-to-earth approach, Blickle is an educator and photojournalist who has worked with horse and livestock owners since 1990 teaching manure composting, pasture management, mud and dust control, water conservation, chemical use reduction, firewise, and wildlife enhancement. She teaches and travels North America and writes for horse publications. Blickle and her husband raise and train their mustangs and Quarter Horses at their eco-sensitive guest property, Sweet Pepper Ranch, in sunny Nampa, Idaho.

Alayne Blickle, a lifelong equestrian and ranch riding competitor, is the creator/director of Horses for Clean Water, an award-winning, internationally acclaimed environmental education program for horse owners. Well-known for her enthusiastic, down-to-earth approach, Blickle is an educator and photojournalist who has worked with horse and livestock owners since 1990 teaching manure composting, pasture management, mud and dust control, water conservation, chemical use reduction, firewise, and wildlife enhancement. She teaches and travels North America and writes for horse publications. Blickle and her husband raise and train their mustangs and Quarter Horses at their eco-sensitive guest property, Sweet Pepper Ranch, in sunny Nampa, Idaho. Editorial Director: Stephanie L. Church

Managing Editor: Alexandra Beckstett

Digital Editor: Haylie Kerstetter

Art Director: Claudia Summers

Web Producer: Jennifer Whittle

Publisher: Marla Bickel