The Frustrations of White Line Disease

Learn how to detect and manage this insidious hoof infection

An infection has been simmering in your horse’s foot. It gave little indication it was there until it had invaded extensively into the hoof’s deep tissues. Now it’s causing the hoof wall to crumble and your horse to be foot-sore. To add insult to injury, it’s proving incredibly frustrating and difficult to treat. Such is often the case with white line disease (WLD).

It All Begins With a Gap

The term white line disease is actually a misnomer; the white line (the soft, fibrous inner layer of the hoof wall) itself is not affected. Rather, the infection takes hold in the area just in front of the epidermal laminae (the sensitive tissues that attach to the hoof wall and help suspend the coffin bone within the hoof capsule).

“White line disease always occurs secondary to some separation of the hoof wall,” says Steve O’Grady, DVM, MRCVS, a farrier and veterinarian with Northern Virginia Equine, in The Plains. “The separation occurs at the inner part of the stratum medium, which happens to be the nonpigmented, softest part of the hoof wall. Organisms can enter this separated area and proliferate deeper into the hoof wall.”

The organisms involved include opportunistic fungi and bacteria found in a horse’s environment. Studies have shown that, initially, bacteria can be cultured from an active case, but then fungi proliferate and take over. This is why the infection is often attributed to just fungus rather than the more likely mix of fungi and bacteria.

“We don’t even know if what we are calling white line disease is truly a ‘disease’ with a single specific cause or if it is a syndrome related to several causes that happen to have a common endpoint,” says Andrew Parks, MA, Vet MB, MRCVS, professor of surgery at the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine, in Athens, who has a special interest in the equine foot.

What Conditions are Conducive to WLD?

Currently, veterinarians don’t completely understand why hoof wall separation occurs, says O’Grady, but any hoof distortion or change in the foot’s loading pattern can put the hoof wall at risk for it. Examples of hoof distortions include long toe-low heels, club foot, sheared heels, and overgrown hooves. Any structural change alters the forces on the hoof capsule, causing bending or shearing forces within internal structures that might ultimately lead to the hoof wall separating near the white line.

The condition might occur in all four feet, only one foot, or only the front and/or rear feet.

“While it seems to be more commonly seen in more humid parts of the country, the correlation between local moisture and incidence of disease hasn’t been definitively established,” Parks says. There are occasional instances where drought conditions might elicit cracks or an opening along the white line, allowing organisms to access the inner hoof wall. But while white line disease can develop in any climate, it’s more prevalent in wet conditions.

“Wet ground tends to soften the hoof capsule much like what happens to a wooden board that is immersed in water over time,” O’Grady adds. “The softened hoof then is more susceptible to hoof wall separation.”

What are the Signs of WLD?

It is rare to see pain or lameness associated with WLD until the tissue damage becomes more extensive and/or until it has affected sensitive tissues. “Usually the problem is identified by the farrier or as an incidental finding on radiographs,” O’Grady notes.

He describes what you might see if looking at the hooves for a more advanced problem: “It is possible to notice that the hoof capsule shifts to one side with asymmetric dishing or bulging representative of distortion forces on the hoof.”

Parks adds, “In a well-advanced case, the wall becomes hollow and you might hear a difference between areas of healthy and diseased hoof horn if you tap the hoof with a hammer with the foot on the ground. But, unless a person suspects a problem, this isn’t a common practice.”

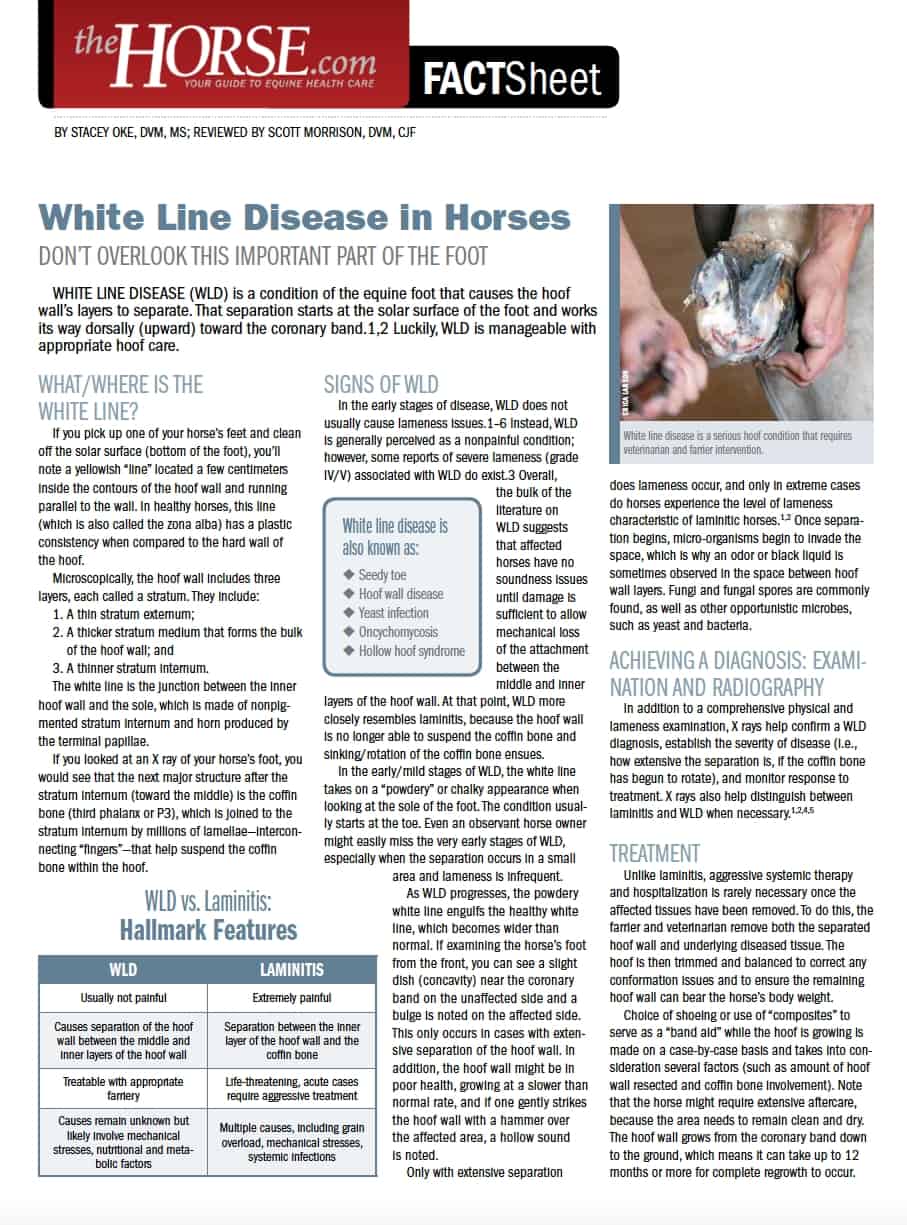

Both of our sources stress that farrier care is central to recognizing an active WLD case. “In shod horses, WLD is almost always identified by a farrier when trimming before resetting a shoe,” says Parks.

The farrier can use nippers or a hoof knife to open the hoof wall-sole junction and better examine the affected area. In a hoof with WLD, a cavity forms within the stratum medium, the depth of which you can measure with an object such as a wire or a nail.

“Other than visual inspection, a (metal or plastic) probe helps delineate the extent of the disease,” says Parks. With diligent hoof care, you can catch and treat a case early; if ignored, the infection can dissect deeper and upward to become more extensive. “There tends not to be as much separation in a barefoot horse as what is seen in shod horses,” O’Grady notes.

If the horse is lame and/or shows hoof tester sensitivity, then have your veterinarian take foot radiographs (X rays) from different angles (referred to as “views”) to determine the infection’s location, the degree and depth of separation, and whether there is concurrent laminitis, says Parks. In the latter circumstance, radiographic images might reveal coffin bone rotation, thickening of the hoof capsule, and/or a gas pocket due to laminar separation within the hoof capsule.

How Can I Manage WLD?

“Because moist environments are conducive to growth of organisms that can create WLD, the best way to manage these horses is to keep their feet dry,” O’Grady advises.

This means employing strategies that prevent an affected horse from standing in puddles that form in unlevel paddocks, by the water tank, or beneath gutter runoff. “Remove the horse from turnout areas that include creeks, wet or deep grass, or mud,” O’Grady says. “It’s best to confine the horse to a small, dry paddock when the pasture experiences wet conditions and also to wait until the dew burns off in the morning before turning out to grass.”

Treatment involves completely removing any detached hoof wall as far upward as necessary to reach healthy hoof horn, O’Grady explains. “Nail infection in dogs and humans begins at the nail bed and grows outward, whereas in horses the infection starts at the ground surface and moves upward. It is important to establish a connection of solid tissue around the perimeter of the resection because that is the area that will be growing down to build new hoof.”

“If enough of the wall is left and the horse has a good healthy sole, I can manage them barefoot,” says Parks. “But, when the distal phalanx (coffin bone) has lost enough support from the laminae— as seen with laminitis—that it begins to cause the sole to drop and sole pressure makes the horse lame, then I would go with a shoe, although the loss of wall can make this more complicated than routine shoeing.”

In cases where the disease has become more extensive, reaching higher toward the coronary band, veterinarians and farriers might take a more aggressive approach. “In order to grow healthy horn, the hoof wall needs continuity of pressure,” says O’Grady. “This can be accomplished by placing a shoe to provide a bridge beneath the missing pieces that have been resected. Then the horse is able to load the foot with an even distribution of weight. Without a shoe, the horse would continue to place pressure and abnormal forces on the diseased area.”

He stresses the importance of your farrier’s planning and preparation before resecting the diseased hoof wall. Putting a shoe on the foot before removing affected dead tissue, for instance, could reserve the farrier enough hoof wall for securing the shoe.

Dr. Steve O'Grady

Following debridement, O’Grady recommends that the farrier avoid filling the hoof defect with composite material, such as plastic acrylic, resin, or urethane; as the composite cures, it heats up and potentially drives organisms deeper into the hoof. He also recommends placing the hoof’s breakover (where the toes pivot forward the moment the heels lift off the ground) behind where you would normally set it (i.e., shoeing further back behind the toe). This relieves stress on the tissues, especially when WLD occurs in the toe.

After hoof resection, clean the foot and keep it clean, O’Grady says. This might entail simply using a wire brush to clean the resected area daily. While many reach for a bottle of some concoction purported to treat white line disease, O’Grady says, “there is little value in putting medication on the resected area that is dry and clean. Despite claims that topical medications are useful in managing WLD, there is no scientific proof that any commercial medication is efficacious.” He does suggest applying iodine, methylene blue, or Thrushbuster (composed of formalin, iodine, and gentian violet) every two weeks as a dye marker to outline disease tracts that need further debridement.

O’Grady describes a study of 25 horses with bilateral (in both feet of a forelimb or hindlimb pair) WLD in which he treated one foot with a commercial preparation and the other foot only with a wire brush cleaning daily. The wire brush-treated feet healed better than the medicated ones. He explains that the wire brushing serves to stimulate the area, keeps it clean, and also keeps the owner’s attention focused on that section of hoof. “A farrier can come at two-week intervals and clean the perimeter with a hoof knife to make sure the hoof tissue is solid and has good integrity and, if not, then diseased tissue is removed as necessary,” says O’Grady.

How Long Until Resolution?

When to return the horse to work depends on how much hoof wall and, thus, coffin bone support has been lost. Parks says, “If a horse needs to go back to work for a specific event, he could do so if the wall is patched; however, just as there can be complications of applying a composite patch after the initial debridement, there is also danger in using it later because if the disease progresses under the patch and the adjacent horn, it eventually becomes worse than before.”

Hoof wall composite patches can still be quite helpful for repairing damaged hooves. If your horse needs one, be sure ot give the diseased hoof sufficient time to heal after debridement before applying it.

In general, resolution takes as long as the hoof wall takes to grow down and fill in the void. If you consider a full hoof wall at the toe requires nine to 10 months to grow, then resection halfway up the hoof means it’ll take four to five months to recover. This requires some patience.

“If the resection extends less than halfway up the hoof wall and the horse is not experiencing any pain or lameness, then he can be put back into work, provided he is fit with an appropriate horseshoe—that is, one that effectively distributes the load with breakover on the shoe rather than on the diseased area of the foot,” O’Grady says.

After WLD resolves, a farrier should carefully examine any future separation because these horses tend to be susceptible to relapse.

Take-Home Message

The primary objectives for preventing and treating white line disease are to increase hoof and hoof capsule strength and minimize moist living conditions for pathogens that might elicit separation at the stratum medium. While hoof strength depends largely on genetics, you can enhance it through the horse’s diet, exercise, environment, and farrier work.

Written by:

Nancy S. Loving, DVM

Related Articles

Stay on top of the most recent Horse Health news with