Introduction

The Many Pieces of the Horse-Buying Puzzle

The purpose behind creating this guide is to give buyers at public auction a short, usable summary of what is important to them regarding the “vetting” process prior to purchasing a prospective racehorse. This information should streamline the buying process; improve communication between the buyer, agent, and veterinarian; and allow the buyer to purchase horses that match his or her individual level of risk tolerance. It is an effort to demystify the process of horse selection at public auction and allow the buyer to avoid obvious problems without unnecessarily missing out on suitable candidates for their program.

Approximately 10 years ago, the Consignors and Commercial Breeders Association produced its first set of educational booklets designed for those involved in the Thoroughbred industry (buyers, sellers, owners, agents, etc.). This latest edition is a compilation of the information presented in the original booklets, updated and simplified with the intent of providing the latest and most important points relative to selecting Thoroughbreds at public auction.

Purchasing a horse at public auction is like taking a jigsaw puzzle out of the box and throwing all the pieces on the table. As you can see from the first image, there are many pieces to the puzzle. Traditionally, the pieces representing radiographic (bone) and endoscopic (throat) findings have been poorly understood and, therefore, magnified in importance compared to some of the other pieces. (Translation: There has been a disproportionate amount of significance given to certain veterinary findings.) The second graphic represents a more balanced approach to buying, with each piece carrying significant weight. Factors such as pedigree, conformation, way of moving, previous sales history, farm of origin, previous surgery, and physical examination can be equally as important as scoping and X-ray findings and can actually help you interpret those findings.

The Sales Setting

Types of Sales

Buying a horse at public auction for the first time is a rite of passage for prospective horse owners. It’s a strange world with its own language and protocol, but with good advisers and, of course, this guide, you should be able to navigate your way through a sale with a certain degree of confidence. Understanding the different types of sales at which you can purchase horses is an important step, but, first, you need to determine at what financial level you can enter horse racing and how quickly you wish to see your purchase on the racetrack, if at all. For example, if you want to race your acquisition immediately, you’re not going to find what you need at a yearling sale. The same is true if you’re looking for a mare to breed the following season.

Once you’ve decided how much you want to spend and how quickly you want to race, breed, or resell, you’re ready to find a sale. And to help you choose, we’ve included some descriptions of the different types of sales and the estimated time frame in which you can expect your purchase to make it to the track — if racing is your goal.

Yearlings are horses that are 1 year old. All Thoroughbreds age one year on January 1, regardless of the month the horse was born. Newly turned yearlings can be sold starting in January, but most yearlings are not sent to auction until at least mid-July.

Key yearling sales include the Fasig-Tipton Saratoga sale, held each August; the Fasig-Tipton Kentucky July select sale and its fall sale in October; the Ocala Breeders’ Sales’ (OBS) August select sale; and the Keeneland September yearling sale. (Select sales offer horses that meet certain pedigree and conformation criteria as determined by a sales company’s selection committee, which examines yearlings for an auction. An open sale is just that — open to any horse.) Most states that support Thoroughbred racing have a sale that offers yearlings, so you should be able to find a sale near you. Or, you could travel to one of the larger sales, if that fits your budget.

Many buyers prefer to purchase later in the year after yearlings have had time to mature and grow. If a yearling is purchased in the fall, the owner can begin breaking/training lessons to prepare it for a racing career, which usually begins in the spring or summer of the horse’s 2-year-old year. Yearlings geared toward quick resale in the 2-year-olds in training sales also are broken in the late fall/early winter so they can showcase their racing potential for prospective buyers.

Two-year-olds in training sales consist of horses that turned 2 on January 1 and are in training — i.e., learning how to breeze and break from the gate, with the hope that they will start racing later in the year. This type of sale offers a quicker rate of return for buyers who don’t want to wait a year or two to see their investment hit the track.

Many of the 2-year-olds entered in these sales are “pinhooks,” meaning they were sold as weanlings or yearlings and are now being resold in expectation of a better price. The hope is that the 2-year-old has improved in looks (“filled out”) over the winter and shows some speed and talent for running.

Two-year-olds in training sales are held mainly from late winter through the spring and early summer, beginning in late February with the Fasig-Tipton Florida select sale. Other major 2-year-olds in training sales include the Barretts select sale in March and Mayand the OBS sales in March, April, and June. A few days before a 2-year-olds in training sale, the horses will sprint a furlong (eighth of a mile) or two furlongs (a quarter-mile) as fast as they can in “training previews” (might also be referred to as breeze shows) to showcase their precocity and speed.

Breeding stock/mixed sales primarily offer broodmares but can include horses of racing age, yearlings, weanlings, broodmare prospects, and stallions. Mixed sales that include weanlings are limited to the fall. Weanlings are horses that have been separated or weaned from their mothers between four and six months of age but haven’t turned 1 yet. A broodmare and her weanling colt or filly often will go through the same sale. For persons wanting to invest in the breeding side of the horse business, buying a broodmare is a way to begin. Buyers usually purchase weanlings with the intention of reselling them as yearlings. As with buying yearlings, purchasing weanlings requires some ability to see into the future and predict how the horse will develop. This can be tricky, so if you decide to purchase weanlings, be sure to enlist the aid of a horseman who has a proven “eye” for picking young horses.

Prospective buyers can find mixed sales throughout the year in all regions of the country, held by state breeders organizations and various sales companies. Key broodmare and weanling sales include the Keeneland January horses of all ages sale and November breeding stock sale; the OBS mixed sales in January and October; the Barretts mixed sale in January; and the Fasig-Tipton November sale. The first two days of these sales, although not called the “select” portion, generally have the highest quality of stock scheduled to pass through the ring.

Horses of racing age sales differ from 2-year-olds in training sales, even though 2-year-olds are technically “horses of racing age.” A few auctions include older racehorses (ages 3 and up) in their catalogs. If, as a prospective buyer, you want instant gratification, this is the type of sale to attend. It is the equivalent of buying a racehorse privately or claiming a horse from a race, but in a more formalized setting. Some of the horses in a horses of racing age sale may not have raced yet, as is the case with many 2-year-olds, even in the fall. These horses might be unraced because of minor injuries sustained in training, or their owners might not have deemed the horses mature enough physically and/or mentally to race. You should have a trainer, preferably one familiar with the horses in the sale and their training and/or racing efforts, to help you evaluate them. Main horses of racing age sales include Keeneland’s January horses of all ages sale; the OBS June sale and winter mixed sale; the Fasig-Tipton July selected horses of racing age sale; and Barretts May sale and paddock sale in July.

Catalog Information

You can get a catalog for any sale by contacting the sales company offices and requesting one by phone or email. Also, you might ask to be put on a list to receive catalogs for any upcoming auctions. Most sales companies have their catalogs online at their websites, making it possible to simply download the information you need.

How to Read a Catalog Page

A catalog page can seem confusing and intimidating at first glance. What do all those names and terms mean and how do you use them? Don’t worry. Use the pointers below to familiarize yourself with a horse’s catalog page, and you will quickly learn to interpret the information to help you decide which horse you want.

Yearling Catalog Page

- The number identifying the horse, appearing on its hip.

- The horse’s pedigree, traced three generations. At each generation the sire appears on the top and the dam on the bottom.

- The horse’s birth date.

- A synopsis of the sire’s racing record and notable progeny.

- A synopsis of the first dam’s racing record and progeny.

- The maternal grandmother.

- A synopsis of the racing record of the second dam’s most prominent offspring. Each indentation represents one generation.

- The maternal great-grandmother.

- Bold capital letters for a horse’s name indicate the horse is a stakes winner. If its name appears in bold lowercase letters, the horse is stakes-placed.

- Indicates the stakes race is graded and which grade.

- Many states have special racing opportunities restricted to horses bred in their state. This will indicate if the horse is eligible for such a program.

- A listing of upcoming stakes races to which the horse has been nominated.

- The horse’s name. If unnamed, the horse is described by sex and color.

- The name of the consignor (the farm or individual selling the horse).

- The barn number where the consignor is located.

Conditions of Sale

When your catalog arrives, you’ll want to jump right in to the pages of horses being offered. But take a moment to read those pages you skipped at the beginning of the book. The conditions of sale are not as much fun as the pedigrees, but you should be familiar with them before you bid.

Buying a Thoroughbred at auction is a commercial transaction, not a consumer transaction. In the Thoroughbred business, the buyer, seller, and sales company are bound by the conditions of sale printed in the front of the catalog. These are the rules and regulations that cover business, ranging from extension of credit to resolution of bidding disputes and other particulars. They also spell out any limited warranties that might apply to horses’ physical defects, including when a buyer can return a horse that turned out to have a specific defect. Conditions of sale vary in comprehensiveness among companies, so review each company’s conditions before attending one of its sales.

Although the particulars regarding limited warranties might vary slightly, horses are generally sold “as is” at a public auction, but certain physical conditions must either be announced when the horse goes into the ring or disclosed by veterinary certificate in the repository. Failure to disclose pertinent information—such as whether the horse is a cribber, wobbler (has a neurologic condition resulting from spinal cord compression), a ridgling (one or both testicles have not descended), or a twin; has an eye defect; or has had invasive joint surgery, upper respiratory tract surgery, or abdominal surgery—can be grounds for rescinding a purchase, provided the purchaser notifies the sales company in writing within the prescribed right-to-return time frame set forth in the conditions of sale.

The time frame for returning a horse and the method used to resolve disputes related to physical condition vary according to the horse’s physical condition and the sales company.

How to Approach a Sale

Owning and racing Thoroughbreds can be one of the most enjoyable experiences in life. Just like with all other endeavors, a sensible approach and the insight of competent advisers will provide the best opportunity for success.

How Sales Work

How to Navigate a Sale

Buying at auction requires more than just showing up, finding a horse you like, and making a bid. New buyers need to do their homework, which ranges from introducing yourself to auction company officials to understanding the conditions under which horses are sold. New buyers also need to learn the protocols of participating in an auction. The following section covers some of the key areas of the auction process as well as how to develop your business plan.

Credit Application

The sales company collects payment on behalf of consignors. A variety of payment methods are accepted, from cold cash to credit cards, including personal check, company check, cashier’s check, traveler’s check, or wire transfer. But even if you bring a valise packed with greenbacks, it’s best to register with the sales office and notify them of how you intend to pay before you bid. A credit application form, or a buyer registration form, can be found at the front of the sales catalog or on sales companies’ websites. Provide your billing address, name and address of your bank, account number, the name of a bank officer the sales company can contact, and the amount of money you expect to bid, so the sales company can run a credit check.

Credit approval can take anywhere from a half-hour to a couple of days, depending on the information you supply and your bank’s cooperation. The right way to obtain approval is to send in a credit application a couple of weeks in advance. If you show up to the sale without approved credit, you’ll have to fill out a lot of detailed credit information first and then wait.

When you register as a buyer, notify your bank that the sales company will be contacting it to check your credit standing. When you arrive at the sales grounds, check in with the sales office before you bid to be sure you have been approved.

Sales companies will allow you a 15-day grace period to settle up on your purchases.

Developing a Business Plan

Don’t count on good luck to stay in business. Instead, plan thoughtfully and specifically so you can still succeed with less-than-average luck and can prosper if good fortune embraces you beyond expectation. As in any other business, start with a sound business plan.

Creating a smart business plan for buying yearlings, especially as an end-user, involves a projection of at least five years. At least two or three years are required to establish and grow the basic operation, and another three or more may be required to produce meaningful results. If you are buying yearling fillies to race with the intention of building a broodmare band, you may be wise to create a seven to 10-year plan, as it typically takes longer and is more expensive to get established in a four-step (buying, racing, breeding, and then selling or racing) scenario.

Also similar to establishing any other business, the single most important prerequisite for success is making sure you are sufficiently capitalized for your objectives and are not risking money you cannot afford to lose. Construct conservative cash flow charts that include all keep and interest charges, and be sure to have sufficient capital for the first four or five years while you wait for returns. Unless you are sufficiently wealthy, be prudent when borrowing or avoid leveraging altogether, building instead on cash reserves as your operation goes forward. As the New Thoroughbred Owners Handbook, published and available from the Thoroughbred Owners and Breeders Association (TOBA), based in Lexington, Kentucky, points out: “Horse ownership is a gamble and you must determine how much you are prepared to gamble for the thrill of owning your own sports franchise.” In this high-risk enterprise, possessing enough restraint to stay within your means defines the difference between gambling and investing.

Once you have developed your systematic business plan, stick to it. Of course, you need to evaluate it each year and fine-tune certain features as you go along. But develop the discipline to maintain a steady course long enough for the program to mature and produce cash flow. Whenever you tweak your program, be sure your revised short-term objectives clearly fit your long-term plan.

Finally, don’t rely only on yourself. At all levels put in place the very best people who are experienced, competent, sensible, reliable, and honest.

Buyer Responsibilities

As part of the sound business plan, you are responsible for selecting your advisers, including bloodstock agents and veterinarians. Just as in hiring key employees for any other business, you should check out candidates’ references and track record and personally interview prospective advisers to make sure they are a fit for your specific program. Taking care to assemble a team of competent and trustworthy professionals is not only good business, but it also increases your probability of success and minimizes any problems that might arise after the fall of the hammer.

Should you need help identifying candidates or assessing a candidate’s credentials, you can contact the major sales companies, as well as TOBA. They are there to serve you:

If you will not be evaluating the sales yearlings and bidding and signing tickets yourself, you will need to obtain the services of an agent. In addition to interviewing prospective agents and checking their documented history of selecting successful racehorses, acquaint yourself with the work of the Sales Integrity Task Force (salesintegrity.org), under the aegis of TOBA.

While on the sales grounds and prior to bidding and purchase, you also have the responsibility to ask questions of consignors about issues that are important to you. If you encounter puzzling situations, feel free to speak to sales company representatives.

Sellers, in turn, have the ethical and legal obligation to answer any questions you ask, factually and honestly. All CBA members have taken a Code of Conduct pledge to disclose pertinent facts when asked and to avoid misrepresentations.

Building Your Team

The insight of competent advisers will provide you with the best opportunity for success. No one has expertise in all areas of a business, and the Thoroughbred business is no different. It is essential to evaluate critically not only the individual horses you might be interested in buying, but also the way those horses fit into an overall plan suited to your unique goals and level of risk tolerance. Your role as an owner is to understand and communicate clearly your goals to your advisers. You might want to purchase to race, breed, resell, or all of the above. Many owners like to learn from their advisers so they can be more involved in the selection process; others prefer to hire the best and let them do their jobs.

The experts who can help the most generally fall into four categories: advisers/consultants, bloodstock agents, veterinarians, and trainers. You don’t necessarily need to hire one of each. It depends on what you want to do with the horses you intend to buy. If you are considering pinhooking, for instance, then you might never need a trainer. If you want to buy horses to race, then your trainer will probably want some say in what winds up in his or her barn. There is some crossover among the four categories. For example, an adviser might also be a bloodstock agent or a trainer. If an expert is wearing several hats, however, then a new owner needs to understand clearly how that expert is primarily making a living to avoid or recognize bias in the advice given.

Regardless of the category, the experts you choose should be intelligent, honest, experienced, and eager to communicate. Equally important is compatibility. You will be spending a lot of time with these people, so you had better enjoy their company.

Advisers/Consultants

One of the most important people you will find is an adviser or mentor. You must have someone who is looking out for your interests first, a trait that is not always the case for experts in the other three categories.

A good first step toward finding that trusted adviser, or any expert, would be to call TOBA, which has readily available a slew of information for new investors. TOBA can also provide you with phone numbers and contacts for every major state Thoroughbred association.

Your next step is to work the phones. Call the president or executive vice president of your state association and get the names of five more people that individual would recommend as advisers. If no one with the association can make recommendations, at least get the names of people who can offer credible referrals. Then call the major sales company or companies in your region and get five more names from each. If you live near a racetrack, call a couple of the leading trainers (racing secretaries can help you find them) and get five more names from them. Take time and get references from the best people available.

Advisers may be farm owners or simply individuals who are knowledgeable about conformation, pedigrees, and market trends and whose sole job is to find good horses for their clients.

Some advisers work for a flat fee, some will get a percentage of a horse’s purchase price, and some might become partners or agree to a percentage of any profits made when horses are sold. Know up front and have clearly defined what is expected and how the expert will be compensated.

Bloodstock Agents

This job can encompass a variety of roles. Critically evaluating the pedigree, conformation, and athleticism of an individual sales horse is typically done by the agent, leading to the decision as to whether the horse has all the ingredients to allow it to stay on the “short list.” The agent also has the ability to facilitate the transition of the horse, once purchased, to the next level, whether it is into training or preparation for resale. Agents have pre-existing relationships with competent trainers and consignors that allow them to act on owners’ behalf in making decisions regarding the horse’s future.

Bloodstock agents can make good advisers, but their primary business is to buy and sell horses. As buyers, bloodstock agents will discuss what type of horse you want to buy and what you can expect to pay. They will look through the horses offered and help create that short list. Then they’ll bid on the horses you are interested in. As buyers, bloodstock agents typically charge about 5 percent of a horse’s purchase price for their commission. As sellers, agents also get an average commission of 5 percent on a horse’s purchase price.

Be wary of agents who claim they can do it all. Most bloodstock agents say it is nearly impossible to buy and sell horses at the same time and do a good job at either.

Veterinarians

The veterinarian’s job is to examine the horses the buyer is interested in; generate a list of findings based on physical examination, endoscopic examination of the upper airway, and review of radiographs; and interpret the findings with regard to potential risk relative to racing and/or resale. The examination process, although thorough, is limited in scope and must be performed within a small window of time prior to the horse going through the ring.

Do not expect your veterinarian to say, “Buy this one,” or, “Don’t buy that one.” Most veterinarians see themselves as educators and facilitators between buyers and sellers, not as providers of a pass/fail judgment. They gather all the information requested on a horse, evaluate the data, and then present their findings to you so you can make the final decision.

Trainers

The closer a sale prospect is to getting to the racetrack, the more likely a trainer will attend a sale to look at it. Trainers are a common sight at 2-year-olds in training sales. Several trainers will also attend the top yearling sales around the country. Trainers usually have their own scouts that sort through the yearlings being offered in a sale and compile a short list to be reviewed when they get into town. A trainer who already has this arrangement is a big plus for you.

If you are interested in racing, know that a trainer’s eye for horses can be invaluable in identifying the ones that might not have fashionable pedigrees but possess the right physical traits to be runners. After all, standing in the winner’s circle is much more fun than buying the most expensive horse in a sale.

The Team

Once you’ve assembled your team, some experts say it is a good idea to spend time at the sales and “trade on paper” first. This way you can refine your goals and criteria before spending any real money. Once you decide to start buying, remind yourself periodically why you’ve assembled a team. You might see your key adviser stop bidding on a horse you love because it has become too expensive or pass on another because of a physical problem. Don’t get frustrated or impatient. Remember to pay attention to your experts’ advice.

The Importance of Vet Work

It’s worth expanding on the veterinarian’s critical role as a member of your team, the reason pre-sale veterinary inspections are so important, and their procedure — starting with your selection of the appropriate vet for your situation.

Selecting a Veterinarian

Agents have pre-existing relationships with one or more veterinarians, and typically the veterinarian selection is based upon that relationship. This is important because timely communication of critical information must occur between the agent and the veterinarian prior to the horse’s going through the sales ring. The selection of an appropriate veterinarian for the team of advisers requires two essential elements: integrity and experience.

If you’re working off a short list of potential veterinarians, interview them. You need to know a few things about what you want to do beforehand, such as what kind of horses you want to buy, their purpose, and the amount of risk you’re willing to assume with your purchases. If you want to buy yearlings, for instance, then you need a veterinarian with a lot of experience looking at young horses. A racetrack practitioner who has experience with both young horses and racehorses is ideal.

A few interview questions that might be informative and useful in your selection of a veterinarian include:

- How much experience do you have with sales, racetrack, reproduction, surgery, radiology, or research?

- How many years have you been doing evaluations at the sales?

- Are most of your clients focused on early racing and resale or are they more oriented toward later or two-turn racing?

- How much experience do you have at the racetrack managing training issues and seeing what actually makes a difference in a horse’s soundness and performance?

- Will you explain your grading system for scopes and X-rays to me before and throughout the sale, and will you indicate what each rating means in terms of research-related racing success?

- What percentage of horses do you “pass” on the scope? What percentage on radiographs? Do you keep track of your sales opinions and how those horses do later on as racehorses?

- At the sales last year, how many yearlings did you “vet” for prospective purchase?

- What percentage of the sales work (scoping, reading and evaluating X-rays, etc.) do you perform versus that by assistants or interns?

- What are your fees for each service you provide?

- Are you available for post-purchase sales work such as preparation for shipping or for representation in any dispute?

- Do you ever have ownership interests in the horses at sales where you work? If you do, do you provide a list of your interests to the sales companies and your clients?

- Will you at some point give me a written report on all of the horses I am paying you to review, detailing your findings and reasons for your opinions?

Veterinarians frequently encounter potential conflicts of interest, so it is incumbent upon all vets to be transparent in their dealings with clients. If, in the process of vetting a group of horses for an agent or owner, a veterinarian sees that he or she has been involved with the horse on behalf of the seller, it is important for the vet to reveal this to the agent so he or she has the option of getting another unbiased opinion. Also, there are times when a veterinarian might be the actual owner of a sales horse, and it is never appropriate for the vet to represent or render an opinion on his or her own horse to a potential buyer.

Amount and type of experience are also important when selecting a veterinarian. It goes without saying that a veterinarian working at the sales should have extensive experience with sales horses, but because these horses need to go on to become racehorses, the veterinarian must also be well-acquainted with any issues likely (or just as important, unlikely) to affect racing performance. It’s not unusual, in the course of performing veterinary examinations, to have findings that are either variations of normal or are not significant to the horses’ future athletic potential.

Veterinarians walk a fine line: On the one hand, they don’t want to miss an important finding, but on the other hand they don’t want to penalize a horse for findings unlikely to affect its racing career. This requires ample, consistent communication among the veterinarian, agent, and owner. There is no doubt risk inherent in buying horses at public auction, but you can reduce that risk significantly by maintaining good communication with and among your team of advisers. Ultimately, it is the agent and the veterinarian’s responsibility to understand the risk tolerance of their buying clients, and it is the client’s responsibility to communicate his or her level of risk tolerance to the team of advisers.

Steps of a Pre-Sale Veterinary Inspection

Once the buyer has assembled a short list of horses, it goes to the veterinarian. He or she will perform a pre-sale veterinary inspection that includes:

- A thorough physical examination of the horse’s eyes, heart, and limbs.

- With colts, a manual palpation to verify the presence of two normal testicles.

- An assessment of the horse’s body condition and way of moving outside the stall.

- Palpation of the abdomen for the presence of a scar indicative of previous colic surgery as well as for the possible presence of an umbilical hernia.

- An examination of the upper airway using a fiber-optic endoscope, an instrument designed to view the structure and function of the larynx.

- An evaluation of the integrity of the joints in all four limbs (front and hind fetlocks, knees, hocks, and stifles) from the X-rays contained in the sales ground’s repository.

There is no particular order for the different phases of the veterinary inspection process. Due to the short window of time for the inspection, sometimes it is more expedient to examine and scope the horses first; at other times it is better to review the radiographs first and perform the exam and scoping afterward. If time permits, the buyer can request specifically that either the scoping or the radiographic exam be done first.

Taking a Risk Assessment Approach

This is a crucial concept for buyers to understand: A veterinarian is never able to predict whether a particular finding will negatively affect an individual horse’s athletic career. Rather, he or she establishes a level of risk (low, medium, or high) with regard to any given veterinary finding based upon published scientific research, veterinary experience, and consultation. The veterinarian can only say, “This finding has (low, medium, or high) risk with regard to future racing performance when compared to horses without this finding.” Many factors influence a horse’s athletic potential, and rarely does one factor render a prospect unsuitable for consideration.

When the veterinarian categorizes risk and adds together all the factors based upon airway, bone, and physical exam, then he or she can communicate an overall level of risk to the client. This is important for helping the client make the purchase decision and determine value. Often, a buyer might not want to buy a horse at a certain price due to the presence of some risky findings but is willing to buy at a lower figure. Determination of value can be as important to a buyer as the decision of whether to buy. Some buyers have a higher tolerance for risk than others, and, again, it is important for every member of the team of advisers to understand the client’s risk tolerance.

Timetables

A veterinarian’s complete assessment of a sales horse depends to some degree on how far in advance he or she received the short list. Because only a few days exist between when the horses ship to the sale and when they walk to the sales ring, there is only a small window for the veterinarian to examine, scope, and review radiographs. The shorter the interval between receiving the short list and the horse being auctioned, the more difficult it is for the veterinarian to complete a thorough inspection. It takes a significant amount of time to perform a detailed physical examination, endoscopic exam of the upper airway, review a set of 38 radiographs, and then effectively communicate those findings and their risk levels to the buying client. Multiply that by many horses in different barns, and it becomes evident that the sooner the short list is presented to the veterinarian, the better it is for the buying client.

This limited time period and sometimes lack of medical history translate to a limited ability to perform more procedures to find underlying conditions. This “limited scope of examination” is generally considered to be acceptable by industry standards because most horses presented at public auction have not been subjected to the rigors of racing.

The Significance of X-Rays

The Repository

Under the conditions of the major sales, it is the purchaser’s responsibility to inspect a horse before it sells and to review any veterinary certificates on file. As a service to buyers, the major sales companies have set up repositories, or information centers, on their grounds. There, your veterinarian can review radiographs and other veterinary records that consignors submit for the horses they are selling. This allows buyers to conduct thorough prepurchase inspections without running up a large bill obtaining numerous sets of radiographs, and it saves the buying team a bundle of time when a busy sale gets in full swing.

The Importance of X-Rays

As noted previously, sales companies require that any radiographs voluntarily submitted be taken within a certain time frame prior to the horse’s sale date, generally within three weeks at yearling and weanling sales and post-breeze at a 2-year-old in training sale. These images include the knee, hock, stifle, and fetlock joints.

The repository might also contain endoscopic certificates or video endoscope imagery of horses’ upper respiratory tracts, as well as veterinary statements pertaining to physical conditions that warrant disclosure.

Veterinarians representing buyers will, for a fee, review the information in the repository in order to report on any significant abnormalities that might make a horse unsuitable for their client(s).

Common X-Ray Findings

Findings veterinarians commonly see in the joints of sales horses can be developmental and/or traumatic (acquired) in origin. These categories are comparably significant. Factors such as the size and location of the X-ray finding — also known as a lesion — and age of the horse will affect how the veterinarian interprets the lesion’s significance. The chronicity (how long-lasting it is) of the lesion and affected underlying bone might also play a part in a veterinarian’s interpretation. Scientific studies are crucial in the veterinarian’s understanding of lesion importance, and although there are some good studies available, much more needs to be done to improve our understanding of the risks these lesions pose.

For example, veterinarians commonly find fetlock bone chips, in sets of repository radiographs. In yearlings these are typically developmental in origin, whereas in horses of racing age they’re more often traumatic. The fragment’s location dictates the level of risk in purchasing the horse as well as proper management of the horse going forward. A fragment in the back of a hind fetlock might not need to be removed and has minimal chances of causing unsoundness. A fragment in the front of a fore fetlock might cause soundness issues and likely requires surgical removal.

Most of the time, these horses have a good prognosis for future racing soundness after a surgeon removes the fragment. The procedure does, however, require post-surgical time off, which might affect the buyer’s decision. Discuss with your veterinarian factors such as the lesion’s location, size, prognosis, and management.

Similarly, the significance of bone chips in the knee varies depending on their size, location, and chronicity. A small, fresh chip in the upper knee joint carries a far more positive prognosis than a large, chronic chip in a lower knee joint, which poses a poor prognosis.

Veterinarians also frequently evaluate osteochondritis dissecans (OCD, a cartilage disorder characterized by the presence of flaps of cartilage and bone or loose bone fragments within a joint) lesions on repository radiographs. An OCD lesion’s size and location will dictate its significance to the horse and the buyer. The mere presence of one or more OCD findings in a horse is not necessarily bad — again, it depends on many factors. A shallow OCD in a one area of a stifle joint does not usually pose a significant risk for unsoundness, whereas a deep OCD in a different area of the same stifle would put the horse at moderate risk for developing lameness.

Also take into account the horse’s age. An OCD finding in a weanling or a yearling might progress and become clinically significant, whereas that same finding in a 2-year-old that is training sound might be insignificant. The veterinarian’s job is to communicate accurately and succinctly a summary of the radiographic findings and put their meaning and risk level into an understandable form for the buyer and/or agent.

The Radiographic Report

After a veterinarian takes radiographs of a sales horse for the repository, he or she generates a list of findings called a radiographic report. This report is intended for the seller of the horse and is a written way of communicating to the client what bone abnormalities might be present and their significance. It does not take into account the prospective buyer’s intended use or level of risk tolerance.

Problems arise when this report leaves the hands of the person for whom it was generated and circulates among interested buyers that have no relationship to either the veterinarian or the seller. These reports are by nature subjective and, as such, only have meaning in the context of a vet-client relationship where both parties clearly communicate and understand the level of risk and intended use. Passing these reports around not only does a disservice to the buyer by creating a potentially false sense of confidence in the information, but it also creates significant legal exposure for the consignor, veterinarian, and sales company.

Furthermore, to date there has been no standard established for which findings are reportable and which aren’t. The notations “no significant findings” and “no significant abnormalities” on these reports are problematic because their significance is in the mind of the individual reviewing the radiographs. Different veterinarians might interpret the same finding differently. In a strict legal sense, the true importance of a finding lies in whether it’s significant only in the mind of the buyer.

Take-Home Point

Most horses have one or more radiographic findings. Some of these are significant, and some are not. The significance of these findings is based on many factors (e.g., location, size, horse’s age, etc.) and it is the veterinary adviser’s job to interpret that information and communicate any level of risk to his or her buying client. A radiographic report at the sale is not like a CARFAX.

Stakes Winners With X-Ray Issues

Carina Mia

Grade I and multiple graded stakes winner

- Right front fetlock (ankle): Irregular lateral condyle (the outer part of the end of the cannon bone that fits into the fetlock joint) due to well-healed fragment

- Left front fetlock: Arthroscopic surgery

Conquest Enforcer

Multiple stakes winner

- Left front fetlock: Bone remodeling

- Right front fetlock: Sesamoiditis (bone inflammation at the back of the fetlock)

- Left tarsus (hock): Tarsometatarsal (TMT, lower hock) tarsitis (inflammation)

Exaggerator

2016 Preakness Stakes winner and multiple graded stakes winner

- Scope: IIA

- Left tarsus: Slight spurring on the TMT joint

- Right tarsus: Old trauma to the third tarsal bone

Farda Amiga

2002 Kentucky Oaks winner and multiple graded stakes winner

- Left and right stifles: Cystic lesions

Nemoralia

Multiple Grade 1 placed and stakes winner in Europe

- Left front and hind fetlocks: Mild sesamoiditis

- Right hind fetlock: Elongated left sesamoid

Suddenbreakingnews

Graded stakes winner

- Bilateral cryptorchid (neither testicle has descended)

- Left hind fetlock: Mild sesamoiditis

Uptown Twirl

Multiple stakes winner

- Right hind fetlock: Remodeling of the midsagittal ridge (a prominence of bone within the fetlock joint)

- Right tarsus: Mild remodeling of the TMT

The Scoping Process

“Scoping” is the term used to describe an endoscopic examination of a horse’s upper airway. The veterinarian passes a fiber-optic endoscope (a long, flexible tube with a light source at one end and a viewing scope at the other) through one of the horse’s nostrils and up the nasal passage to evaluate upper airway (larynx and pharynx) health, structure, and function. A number of conditions can potentially affect a horse’s upper airway and subsequently reduce the amount of oxygen available for maximal athletic activity. These abnormalities are covered in the Conditions of Sale found in the beginning of each sales catalog. It is every buyer’s right to have his or her purchased horse scoped post-sale to ensure its upper airway meets Conditions of Sale. If not, the horse is subject to return. Many buyers elect to have the horses on their short list scoped at the same time their veterinarians perform physical examinations prior to bidding.

Grading System

The upper airway evaluation is based on an internationally accepted and standardized grading scale (called the Cornell scale) of the arytenoid cartilages. These cartilage flaps are responsible for opening the throat during inspiration of air and closing the throat during expiration and swallowing. The scale is as follows:

- Grade 1: The arytenoid cartilages are able to open (abduct) maximally, and they do so symmetrically.

- Grade 2: The cartilages are able to abduct maximally, but they are not symmetric in doing so. Grade 2 airways are divided into two categories: 2A for mild asymmetry and 2B for moderate asymmetry. Grade 1, 2A, and 2B airways are all within the realm of normal. There is a common misconception that a Grade 1 airway is superior to a Grade 2A or 2B airway, but retrospective studies following the racing performance of thousands of Thoroughbreds show that horses with these airways perform equally well.

- Grade 3: One of the arytenoid cartilages is not able to abduct fully. This is considered to be abnormal function and is covered in the Conditions of Sale.

- Grade 4: One of the arytenoid cartilages (more often the left than right) is paralyzed completely.

Veterinarians also evaluate the structure and function of the epiglottis, which covers the opening of the larynx during swallowing, as abnormalities can contribute to a condition called dorsal displacement of the soft palate. The epiglottis can appear normal to mildly flaccid, moderately flaccid, or severely flaccid. Its length can be described as normal or short. Horses that “displace” during racing or training tend to make an airway noise during expiration, which can indicate reduced airway function and, thus, performance. An epiglottis of appropriate length might appear normal, mildly flaccid, or even moderately flaccid and still be completely normal in function.

Veterinarians also evaluate the pharynx for abnormalities. Pharyngitis is an inflammatory condition of the upper airway that is common at sales due to horses’ exposure to many other horses in close conditions. It is usually selflimiting, meaning it heals on its own, and unlikely to be a factor in horse selection.

Veterinarians have historically performed endoscopic examinations of the upper airway in the standing, or resting, horse. This does not, however, closely approximate how the airway functions during maximal activity such as training and racing. The resting exam is designed to screen for obvious abnormalities, and some upper airway conditions can only be diagnosed using dynamic endoscopy during training over ground or on a treadmill.

Videoendoscopy

Scoping at the Sales

This veterinary procedure has been gaining popularity as a way of evaluating a horse’s airway function on a pre-sale basis. The veterinarian performs and records the examination in a stall several days prior to the horse’s selling session, making the video available for subsequent buyers’ veterinarians to review. The obvious advantage to this tool is that it reduces the number of scopings popular sale horses must undergo, therefore reducing the risk to them and their handlers. The perceived disadvantage is the question of whether the video represents the airway accurately and to the satisfaction of the buyer and his or her veterinarian. The use of videoendoscopy as a pre-sale tool for evaluating sales horses is a work in progress. The American Association of Equine Practitioners has adopted a standard protocol for videoendoscopy at sales as a guide for veterinarians to perform the procedure with maximal quality and integrity.

Success Stories

As you’ve no doubt learned by now, no horse is a perfect physical specimen. And many sales horses with flaws that might cause buyers to balk go on to have extremely successful racing careers. The following are a few examples of less-than-perfect horses that outperformed their questionable radiographic or endoscopic findings.

Normandy Invasion was purchased as a colt for $145,000 at the 2011 Keeneland September Yearling Sale. He was put into training and then resold at the 2012 Keeneland April 2-Year-Olds in Training Sale for $230,000.

On his repository radiographs, Normandy Invasion showed evidence of sesamoiditis (inflammation of the sesamoid bones at the back of the fetlock) that exceeded some buyers’ risk tolerance. As a racehorse, however, he performed at the highest level, finishing second in the Grade 1 Wood Memorial and fourth in the Kentucky Derby Presented by Yum! Brands in 2013. He ultimately earned more than $550,000 in graded stakes company.

Awesome Gem was purchased as a colt at the 2004 Fasig-Tipton Saratoga Select Yearling Sale for $150,000. On endoscopic examination of his upper airway, he exhibited Grade 2B function. In other words, his throat function was moderately asymmetric. Although some buyers express concern when upper airway asymmetry is more than mild, the fact that this horse’s airway was normal was born out in the fact that he was a Grade 1 stakes winner earning almost $2.9 million over the course of seven years and 52 starts.

Executiveprivilege was purchased for $23,000 at the 2011 Keeneland September Yearling Sale. Her repository radiographs revealed that she had an OCD lesion in her right stifle. A finding of that depth and in that location carries a moderate level of risk regarding the development of lameness, and the veterinarian communicated this information to the buying client prior to purchase.

If it weren’t for the OCD finding, Executiveprivilege likely have brought more money at the sale, but a reduced purchase price is the usual trade-off for taking such a gamble. The client was willing to take on the risk at that price point. If that particular radiographic finding is going to lead to unsoundness, it usually happens early in the training process. This filly did not develop any lameness related to the stifle finding and presented well at the 2012 Ocala Breeders Sales Company’s April 2-Year-Olds in Training Sale where she brought $650,000. She went on to become a multiple Grade 1 stakes winner earning just shy of $1 million.

The “OK to Race, Not OK to Pinhook” Conundrum

The phrase “OK to race, not OK to pinhook” frustrates many people in the Thoroughbred industry. In a perfect world, a horse that is suitable for racing ought to have the same level of suitability for purchasing to resell. It seems intrinsically unfair that a horse with no issues preventing it from being a good racehorse should be penalized in the context of a sale.

There is another way of stating this unfortunate truth that makes it more understandable and acceptable, and it is couched in terms of risk. Once a veterinarian evaluates a horse at a sale (via a physical examination, endoscopic exam of the upper airway, and radiographic exam of the joints), he or she generates a list of findings. These findings can carry a low or mild level of potential risk to future racing soundness. However, buyers with less experience or lower levels of risk tolerance might interpret these same findings as more significant, thereby raising the level of risk for resale to medium or moderate. So, the difference between suitability for purchase for racing versus purchase for resale has everything to do with how risk-averse the buyer is. If everyone had the same posture on risk posed by veterinary findings, then “OK to race” would be the same thing as “OK to pinhook.”

Conformation and Anatomy

Near perfect individuals such as Secretariat don’t come around very often. Virtually every horse has some fault, especially if it is an observer’s nature to find fault. However, a preoccupation with fault-finding is frequently unproductive, as most graded stakes performers have conformational flaws and come in all shapes and sizes.

Evaluating a Horse’s Physical

Given this reality, your most important sales assessment task is to try to figure out whether a particular fault is likely to compromise future racing success. Therefore, learning to evaluate a horse’s conformation and movement as an athlete properly is an essential skill to acquire.

Desirable characteristics in any horse include balance and good proportion, musculature, and bone mass. When initially assessing a horse, knowledgeable buyers also consider whether the horse has “presence” and intelligence.

Although a horse should be judged as a whole rather than a collection of individual parts, it’s important to scrutinize the components and learn to observe, describe, and evaluate the degree of a fault.

It is common to hear a yearling’s faults described in very general ways: “He’s offset,” or “he toes in.” Simplistically saying that a horse is “offset” or “toes in” or “toes out,” however, has very little meaning unless the degree is also mentioned. Experienced and competent professionals use various methods of note-taking and descriptions to record the degree of a fault. A common one is the 1-2-3 method: 1 = slight, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe. You can refine the assessment further by using pluses and minuses, as in 1, 1+, 1++, 2-, 2, 2+, 3.

Whatever your evaluation or recording method, training yourself to think in terms of the degree of a conformational flaw helps you define how difficult it might be for a horse to manage himself so the fault does not significantly impact soundness or performance. Plain and simple, making decisions based on an accurate assessment of the severity of the fault will help your long-term success, because most horses handle minor to moderate degrees of deviation successfully, if they move in a fluid and athletic way.

Regarding movement, experienced buyers always watch a horse walk, looking at it from the side and front. Many conformation defects manifest as a horse moves. It requires looking at hundreds, even thousands, of horses to develop an eye for conformation. Take the time to watch as many horses as you can, whether at the sales or in the paddock of a racetrack.

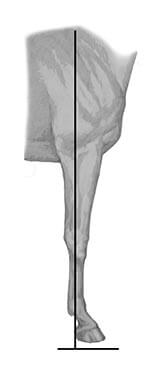

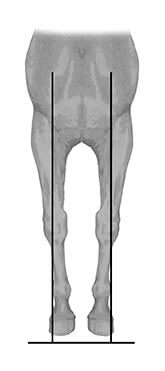

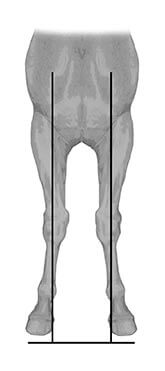

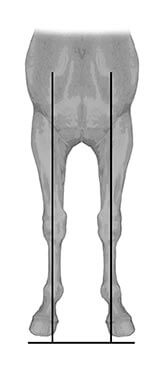

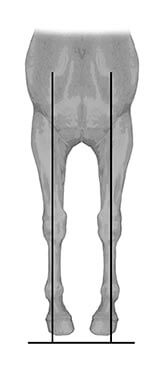

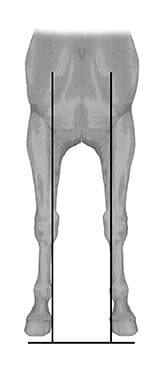

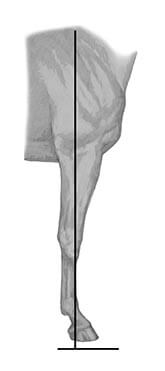

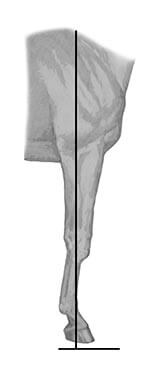

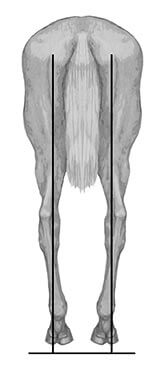

Normal Limb Conformation

Limb Conformation Faults

Glossary of Veterinary Terms

Below is a list of common terms you might hear from the veterinarian about sales horses.

- Abaxial

- Away from the central axis of the organism or extremity.

- Arytenoid cartilage

- Cartilage structures that work like flaps to open the airway and tense the vocal cords when the horse breathes in air. They close the airway when the horse swallows to protect the windpipe (trachea) from feed contamination.

- Avulsion

- A small fragment pulled loose from the bone.

- Chip

- 3-10 mm in size.

- Flake

- 2 mm or less in size

- Fragment

- This term can be used alone or be accompanied with adjectives (small, large, etc.). Usually more important when within a joint; typically of less concern when outside a joint.

- Axial

- Nearer to midline or central axis.

- Bone spurs (osteophytes)

- Sharp bony projection visible on X-rays at joint margins where the articular cartilage (which lies at the ends of adjoining bones in joints) blends into the underlying bone.

- Bony eminence

- Raised calcification on bone not normally present. Can be pointed or smooth, single or multiple.

- Capsulitis

- Inflammation of the joint’s synovial membrane and fibrous capsule with no apparent radiographic involvement of bone or other structures.

- Cartilage

- Firm but elastic connective tissue, especially important in the joints, as cartilage provides both a basis for bone growth and the surface that allows bones to move without producing undue wear.

- Clinical

- An expression of a veterinary condition by a clinical sign or symptom, such as lameness or swelling.

- Coronal plane

- Divides the body into dorsal and ventral.

- Cyst

- A rounded demineralized area in bone. May or may not have a halo or dense bone surrounding it.

- Developmental orthopedic disease (DOD)

- A general term that encompasses all bone-related disturbances of growing horses, including osteochondritis dissecans, some angular limb deformities, physitis, and other conditions.

- DIT

- Distal intertarsal joint (lower hock joint).

- Distal tarsitis

- Inflammation of the lower rows of hock joints.

- Dorsal

- The side of the body normally oriented upward, away from the pull of gravity (think dorsal fins of dolphins or sharks).

- Dorsal displacement

- Backward displacement of the soft palate over the epiglottis. In swallowing, the soft palate normally and momentarily displaces over the epiglottis but returns to its normal position underneath the epiglottis. The term displacement indicates the soft palate has moved on top of the epiglottis and stays there.

- Elongated sesamoid

- Signifies that the height of one or both sesamoids (the bones that sit at the base of the cannon bone in back of the fetlock joint) is taller than normal. Fractured sesamoids that have healed may have an elongated appearance. Not all elongated sesamoids are healed fractures, although most are.

- Endoscopic examination (scoping)

- Use of an endoscope to examine a horse’s upper respiratory tract to determine general health and airway functioning and prospect for racing.

- Enlarged sesamoid

- Can indicate a relative or absolute difference in the size of sesamoids.

- Enlarged vascular channels

- A radiographic appearance of linear or circumscribed loss of bone density in the sesamoid. Could be single or multiple, but always a response to a previous insult that may have healed, or might be pathologic, depending on its appearance.

- Epiglottis

- Muscle tissue that covers the windpipe when a horse swallows. It fits through a hole at the rear of the soft palate.

- Erosion

- A rough, irregular appearance to the surface of bone in question. Usually accompanied by some bone calcium loss.

- Exostosis

- Formation of new bone on the surface of a bone.

- Flattening

- Loss of normal contour to a described area.

- Growth plates

- The physes at the ends of long bones of animals allow the bones to grow in length by adding new cartilage as existing cartilage hardens to bone.

- IC

- Intermediate carpal bone (knee)

- Irregular border

- A loss of regular anatomy to an area. Can be in or outside a joint space.

- Joint collapse

- Indicates narrowing of the joint space due to loss of normal articular cartilage. Could be accompanied by bone fracture, bone fusion, and spurring. These changes might occur singly or in combination.

- Lateral

- Structures near the sides.

- Laryngeal hemiplegia (roaring)

- A condition in which the arytenoid flap becomes completely paralyzed. As a result, the arytenoid and the attached vocal cord obstruct airflow when the horse breathes and produce a “roaring” sound. Most commonly affects the left arytenoid and is often associated with trauma to the recurrent laryngeal nerve that runs down the horse’s neck, around its heart, and back up the neck.

- Lesion

- In relation to an OCD, this is a site of pathology (damage or disease) relative to the cartilage that might or might not involve the underlying bone.

- Lucency

- Area of decreased bone density represented by a dark area in a radiograph; it might be pathologic.

- Deep

- Refers to a lucency that is more invasive in the bone.

- Shallow

- Refers to a lucency that’s more superficial.

- No shed

- No fragments are visible.

- Shedding

- Small or large fragments are displaced from the bone.

- Medial

- Structures near the midline.

- MSR

- Midsagittal ridge, or the middle of the central ridge of the cannon bone.

- Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD)

- A cartilage disorder characterized by the presence of large flaps of cartilage and bone or loose fragments within a joint.

- OCD flap

- A fragment of bone or cartilage that has separated from its parent bone, but it still partially attached.

- Ossification

- Hardening of cartilage into bone.

- Osteoarthritis

- A progressive series of changes that occur in joints and their cartilage surfaces that typically lead to painful loss of joint function. In horses, osteoarthritis is most often secondary to debris created by the presence of fragments (OCDs or chip fractures) within the joint.

- Physes

- The growth plates at the end of the long bones of a horse.

- RC

- Radiocarpal bone (knee)

- Roughening

- Appears as an irregular margin in the radiograph. This can be in the joint or appear outside the joint.

- Rough joint surface

- Indicates a loss of normal smoothness to an articular surface. Can occur due to trauma or could be developmental in young horses.

- Remodeling

- Radiographic description indicating change in the normal bone shape or density.

- Sclerosis

- Appears as lighter (or whiter) in a radiograph, due to greater calcium content than normal and increased radiographic density. This could mean the bone is stronger or weaker than normal.

- Sesamoiditis

- Describes some degrees of inflammation of the ligamentous attachments to the sesamoid bones at the back of the fetlock joint (the sesamoid bones act as fulcrums for the suspensory ligament as it passes over the back of the fetlock joint).

- Sesamoid fracture

- Sesamoid bones act as fulcrums for the suspensory ligament as it passes over the back of the fetlock joint. A fracture of the sesamoid often involves an injury to the suspensory ligament insertion—where it attaches to the sesamoid bones. Depending on the severity of the injury, surgery can be performed to treat the fracture. Sesamoid bones are wider at the base and taper to a narrower top. Veterinarians often refer to sesamoid fractures as “apical” (at the top), “mid-body” (in the middle), or “basilar” (at the bottom). Basilar fractures might occur when a foal is young, his sesamoids are soft, and he runs on hard ground to keep up with his mother. Fortunately, young foals’ bones are very resilient, and fractures often heal sufficiently well to result in racing soundness.

- Spavin

- Osteoarthritis, or a phase of degenerative joint disease (DJD). It usually affects the two lowest joints of the hock (the tarsometatarsal and the distal intertarsal joints).

- Synovial effusion

- Filling in a joint.

- Tarsitis

- Inflammation in the hocks and a precursor of the condition that eventually results in spavin. Almost always indicated in distal intertarsal and tarsometatarsal joints. Refers to some type of reactive change. This may be an acceptable finding in some cases.

- Transverse

- Divides the body into cranial and caudal.

- Upper respiratory tract

- The arytenoid cartilage, epiglottis, and soft palate are the principal structures described in an exam of the upper respiratory tract.

- Ventral

- Side of the body closest to the ground.

Published 2016 by the

Consignors & Commercial Breeders Association

P.O. Box 23359 • Lexington, Kentucky 40524 859.243.0033 • 859.272.1323 (fax)

info@consignorsandbreeders.com • consignorsandbreeders.com

Mission Statement

The CBA works democratically on behalf of every consignor and commercial breeder, large and small, to provide representation and a constructive, unifid voice related to sales issues, policies, and procedures. The association’s initiatives are designed to encourage a fair and expanding marketplace for all who breed, buy, or sell thoroughbreds.

Code of Conduct

Members of the Consignors and Commercial Breeders Association (CBA) are expected to uphold the following professional standards and Code of Conduct:

A CBA Member Will:

- Strive at all times to serve the best interests of his or her client.

- Conduct business with honesty, integrity, and fairness toward clients, other CBA members, and the buying public.

- Answer truthfully and avoid intentionally misleading statements when responding to inquiries from prospective buyers.

- Refuse to pay or accept commissions that are not disclosed to the member’s principal and refuse to participate in any undisclosed dual agency or other fraud.

- Comply with all applicable sales company rules of sale and with all applicable state and federal laws.

CBA Board of Directors

- Joe Seitz Brookdale Sales

President - Jody Huckaby Elm Tree Farm

Vice President - Matt Lyons Woodford Thoroughbreds

Secretary - Kitty Taylor Warrendale Sales

Treasurer

- Jody Alexander Mt. Brilliant Farm

- Terry Arnold Dixiana Farm

- Marty Buckner Clarkland Farm

- Andrew Cary Select Sales

- Pat Costello Paramount Sales

- Jamie Hill McMahon & Hill Bloodstock

- Meg Levy Bluewater Sales

- Frank Mitchell

- Martha Jane Mulholland Mulholland Springs Farm

- Allaire Ryan Lane’s End Farm

- Mark Taylor Taylor Made Sales Agency