As the sun sets on another day in a village rife with poverty, a scrawny donkey begins his evening forage for scraps of grass, weeds, straw, or anything else he can find.

After working alongside his owner all day, taking goods to and from the local market, the donkey has been turned loose—as is custom in the region—to eat, find a puddle to drink from, and fend for himself while his owner uses what little money he’s made to feed his family. The next morning the owner will fetch the donkey for another day of work under an African sun.

Meanwhile, in a lush pasture in the heart of a horse community in the developed world, a Thelwell-esque donkey eats. And eats. And eats. This pasture pet suffers from pulsing pain in his feet caused by laminitis, resulting from continual access to a buffet of rich grass. His owner only accentuates the donkey’s problem, lavishing him with grain, treats, and the same delicious alfalfa hay she uses to feed her horses each night in their stalls.

Though they have long ears and an unmistakable bray in common, these two very similar donkeys face two very different problems.

From hauling goods and people in developing nations to keeping horses company and protecting livestock from predators in developed countries, donkeys play important roles in millions of people’s lives each day. These hard-working creatures also face a number of welfare issues, regardless of whether they toil in the heart of a penurious developing city or eat their fill in an affluent equestrian community.

But people and organizations worldwide are working to improve donkey welfare, from helping owners design and produce donkey-friendly harnesses to educating people about properly feeding their long-eared charges. And, while there’s still much work to be done to improve donkey’s lives, these groups and individuals make progress every day.

Working Donkeys: Dealing with Daily Struggles

“There are an estimated 50 million donkeys and mules in the world,” says Dr. Kevin Brown, international program development manager for The Donkey Sanctuary, in Sidmouth, U.K. However, he notes, donkeys are “often forgotten to be reported or recorded in livestock census surveys, so this figure may be significantly underestimated.”

Kevin Brown, BSc, BVMS, PhD, MRCVS, is the international program development manager for The Donkey Sanctuary, in Sidmouth, U.K.

A great majority of those donkeys, he adds, live and work in low-income areas: An estimated 7 million donkeys reside in Ethiopia, 6.36 million in China, 4.9 million in Pakistan, 3.35 million in Egypt, and 3.28 million in Mexico.

Donkeys Around the World

The top 5 countries for donkey populations, and their most common uses within those countries:

Ethiopia

Ethiopia China

China Pakistan

Pakistan  Egypt

Egypt Mexico

Mexico

Ethiopia

7 million donkeys

Most common use: Rural transportation (carrying water and/or produce and agricultural work)

China

6.36 million donkeys

Most common uses: Transportation in rural areas and trade (on products such as donkey meat, milk, and skin)

Pakistan

4.9 million donkeys

Most common uses: Rural transportation and pulling carts for families who search rubbish dumps for recyclable materials to sell

Egypt

3.35 million donkeys

Most common use: Bringing bricks to and from kilns for firing

Mexico

3.28 million donkeys

Most common uses: Transportation, agricultural tasks, and brick kiln work

The age of these working donkeys varies greatly based on factors including the country in which they reside, their workload, local traditions and culture, how old the animal was when he first started working, and availability of affordable veterinary services.

“It would not be unusual for a 5-year-old donkey to have reached its life expectancy,” Brown says. “However, some working donkeys that are well-looked-after can live to 15 or more years of age.”

The donkey makes an ideal work animal for many people in low-income countries because, on the whole, they’re less expensive to purchase and maintain than horses, he says. But that’s far from the only reason.

Why Do People Choose Donkeys as Working Animals?

“They’re incredibly hard workers,” Brown adds. “They can be trained to do the work. They’re less flighty than horses. They’re incredibly hardy. For their size, they’re incredibly strong—in relation to their size they can often do a disproportionate amount of work. And they’re a desert species.”

This means they can survive on lower-quality fodder than horses and ponies, making their care less costly.

“Donkeys are a vital source of valuable income for the family and the household,” Brown explains. “It’s a symbiotic relationship: The donkey depends on the owner to provide food and basic needs, but so is the owner dependent on the donkey to provide power, to deliver his produce to and from the market, work in construction sites and brick kilns. It’s a very strong relationship.”

Still, these donkeys often go to work bearing wounds and injuries on a daily basis. Brown says The Donkey Sanctuary classifies common issues working donkeys around the world face into five categories:

Behavior problems

These stem from the relationship between the donkey and his handler and, like many other issues, from tradition. “If a donkey needs to go from Point A to Point B, the traditional thing is to give it a good beating; that’s all they know,” Brown says. “Or, it could be the person who’s working with the donkey is actually a child. And their job is to get the donkey from A to B. And if they don’t, they’re beaten themselves, or they don’t get paid.”

Body condition

The second group of problems, Brown says, is related to nutritional status, or how thin or fat the animal is. This can indicate dental conditions, the quality of what they’re eating, and how they’re eating.

Wounds

Another major issue for working donkeys is wounds, which are exacerbated by ill-fitting harnesses.

Lameness

Brown says unsoundness, especially hoof-related lameness, is a prevalent problem in working donkeys.

Everything else

“So those four cover probably about 60% of problems found in a working equine,” Brown says. “And then we have all other signs of injury or disease,” such as infectious, exotic disease and zoonotic disease (which can transfer from animals to humans).

Dr. Eric Davis, founder of the nonprofit Rural Veterinary Experience, Teaching, and Service, based in Dixon, California, says another key challenge working donkeys face is proper access to two things that many owners in developed countries take for granted: food and water.

Eric Davis, DVM, MS, Dipl. ACVS, ACVIM, is the founder of the nonprofit Rural Veterinary Experience, Teaching, and Service, based in Dixon, California, and travels to low-income communities regularly to care for the residents’ donkeys.

“It’s pretty extraordinary what donkeys have evolved to survive on,” he says. “My wife and I are packing to go work on donkeys in the mountainous part of Mexico. And the donkeys that we’ll see down there, they carry a pack up a hill that you couldn’t climb without a rope; they’re like little mountain goats. Their entire caloric intake is basically dried weeds and dried cornstalks. And maybe on a good day they get a bit of mesquite off a prickly mesquite tree. If you tried to feed a horse that way, it’d die.”

Even more important than calories for short-term survival, however, is hydration. And finding any water, not to mention a clean source of it, can be a feat.

“Donkeys evolved to live in extremely arid conditions, so they’ll get by on an amount of water comparable to what a camel drinks,” Davis says—when they’re water-starved, they tend to drink only enough to replace lost body fluids. “So there’s a tendency, then, to figure, ‘Well, they don’t need any water at all,” underestimating their need for rehydration.

“We find in Mexico that the water sources are far apart, and because there are few of them, many animals use them,” he continues. “And there’s a little green rim of grass around that water hole. Well, that’s full of parasites. So it’s not only hard to get water, but the whole process of getting water tends to be a parasite-concentrating mechanism, which is good for the parasites, but not so good for the donkeys. That’s an important problem throughout the world.”

Another contributor to the working donkey plight is the lack of resources for local veterinarians—if practitioners are even available—in poverty-stricken communities.

“A lot of the practicing vets in, say, Ethiopia or remote areas of Kenya won’t even have electricity,” Brown says. “They probably have three drugs. They’d even be lucky if they have fresh water.

“In the ideal world you’ll have a community of very healthy donkeys, and they’ll get ill at some stage,” he notes. “And those animals will then be taken to a well-trained equine vet or animal health worker who provides a service to that community of people. And that happens in some areas, but in many areas that’s not available.”

As a result, many donkey owners handle injuries and illnesses as best they can: “A lot of treatment would be based on traditional remedies (such as turmeric and mustard oil) or traditional healers or no treatment at all,” Brown says.

Suzi Cretney, The Donkey Sanctuary’s senior public relations officer, adds, “There are also quite a lot of rooted cultural beliefs that donkeys don’t respond to treatments and don’t feel pain. So if you believe genuinely that it doesn’t feel pain and wouldn’t respond even if you did treat it, why would you bother? It’s very complicated. Sometimes it’s generations of people who’ve taught (the owners) these wrong ways.”

Suzi Cretney is The Donkey Sanctuary’s senior public relations officer.

Dawn Vincent is The Donkey Sanctuary’s communications director.

Fortunately, organizations around the world are striving to improve the working donkeys’ welfare. And most, such as The Donkey Sanctuary, have learned that community-based approaches appear to be most effective in getting important information to owners.

“These people have great community spirit,” says Dawn Vincent, communications director for The Donkey Sanctuary, “so it’s important for us to get our foot in the door and be respected enough that they’re going to believe what we say.”

Brown says The Donkey Sanctuary staff not only provides education but also works with community residents to understand what they perceive their animals’ problems to be. The staff members compare this information to their own assessment of the animals’ current health needs. “Together we may come up with some solutions to particular problems that are perceived,” Brown says.

He used wounds as an example: “So it could be that in a particular community the donkeys simply aren’t working as well as they used to. And it might be the reason the owners perceive the donkeys aren’t working well is because they have nasty feet. But you might look at a donkey and see it’s got huge festering wounds on its back. It’s not working because it’s in severe pain from trauma.

“(We have to) work together to identify issues, to deliver welfare messages in a participatory way, and to identify solutions for particular problems that may arise, like wounds,” Brown says. “It’s about working with harness makers who are likely doing what their parents did or what’s usual in the area (and based on tradition rather than welfare) by bringing in harness specialists who will tweak the harnesses to reduce wounds by a significant amount.”

The organization’s hard work is paying off.

>

> “I’ve just recently been to India … to look at a community that The Donkey Sanctuary has been engaged in for some time,” Brown says. “We spent the day with them while they were doing really hard work from 4 or 5 in the morning, and finishing at 11 (at night)—the whole family, even the children. It’s a tough life.

“And yet, as a consequence of the work that we’re doing in that particular project, the donkeys are in absolutely fantastic condition, despite the number of hours that they’re working,” he continues. “The owners have decided on a maximum load of bricks per donkey, which is related to the weight of the donkey, so they’re carrying 20 bricks. They’ve learned how to move their donkeys from Point A to Point B without (unnecessary) physical contact.

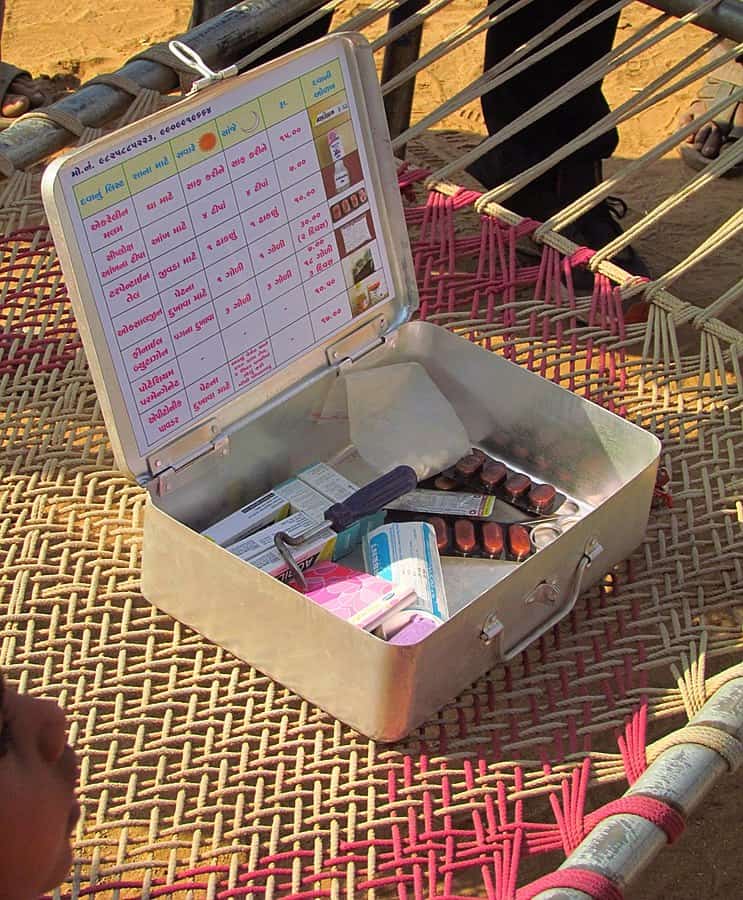

“They have a system where they’ve incorporated developments in harnesses and their backpacks and padding to protect the spine. They even have community animal health workers who take responsibility for a first-aid box (that includes things such as pain relievers, eye medication, antibiotics, and dewormers). They recognize their animals are valuable.”

The lives of donkeys halfway around the world are also improving. Dr. Jay Merriam, who leads relief teams of American Association of Equine Practitioners-member veterinarians for the organization’s Equitarian Initiative, recalls a visit to a village north of Pueblo, Mexico. His team was on Day 3 of a weeklong workshop, and a local resident brought in a small donkey in serious condition.

Jay Merriam, DVM, MS, has worked in private sport horse practice since 1975 and is co-founder of the American Association of Equine Practitioners' Equitarian Initiative.

“(The donkey) was, as one of my old professors had described, a malnourished cow—a rack of bones, held together by hide and hair,” he recalls. The owner—an elderly woman—reported that the donkey had been losing weight over the last months, wasn’t eating, and, worst of all, couldn’t work.

“That was the critical thing,” Merriam says, explaining that this donkey was the sole financial support for this woman and her husband. “They needed her to carry firewood and harvest in preparation for winter, and she could no longer do it. They couldn’t afford a new one, and they couldn’t continue feeding her.”

One of Merriam’s colleagues identified a large hernia protruding from the donkey’s right groin. “The hernia was round, smooth, and irreducible (it couldn’t be squeezed back into position or reduced), a bad sign in any case,” he recalls. “But in hers, it meant that a loop of intestine was trapped in (the hernia), and it was slowly strangling her food supply.”

The team explained the options to the owner, including euthanasia.

“The euthanasia option is rarely accepted in the developing world,” Merriam explains. “In most cultures, death is seen as the choice of whatever almighty force they hold dear, and animals like this are often turned out, abandoned and forced to starve to death, or suffer until death—from whatever disease they have—takes them.”

The owner asked Merriam and his team to try to fix the donkey’s hernia. “She and her husband had actually been feeding and caring for the donkey, (who) had been in the family over 20 years. She even had a name, which meant ‘flower’” in the local dialect.

“That’s something very rare in any culture, that a working equid is named,” Merriam says.

Surgeons attempted to repair the donkey’s hernia, but they found additional complications and the owner finally agreed to euthanasia.

Merriam knew it would cost roughly $400 to buy a new donkey, which the couple didn’t have. He began raising funds among his colleagues to assist, but before he could collect the money, program co-chair Dr. Mariano Hernández Gil of the University of Mexico (UNAM) found a UNAM research donkey to donate to the couple at no charge.

“What a joyful face the owner put on as Mariano explained that a new donkey was on its way,” Merriam says. “There was no false pride, no refusal to take this gift, as I might have anticipated, only genuine sighs of relief, one for the ending of the suffering of their long-time helper, but also for the realization that life would continue in their village, (they’d be) able to care for themselves and contribute. And this was the gift that we were able to give. Life for the new donkey won’t be easy, but he’ll be cared for and so will they.”

Donkeys in Developed Countries: Killing Them with Kindness

Turning our attention back to the donkey down the lane that’s ear-deep in lush grass, we recognize that working donkeys aren’t the only ones facing dire welfare challenges. Donkeys in developed countries are subject to a set of issues centering around one fact: Owners, veterinarians, farriers, and anyone involved with caring for a donkey don’t always realize that these animals are not horses.

“Donkeys look a lot like horses, but are different in key areas,” says Dr. Nora Matthews, professor emeritus of anesthesia at Texas A&M University. “They are a different species and are physiologically desert-adapted, which leads to differences in how they handle drugs. There are multiple subtle anatomical differences, including hoof shape and angles, lack of chestnuts, and different placement of nasolacrimal (tear) ducts.”

Nora Matthews, DVM, Dipl. ACVA, is a professor emeritus of anesthesia at Texas A&M University and an authority on donkey health.

But one of the most important differences between these animals and their horse cousins is the amount and type of food they need.

“Donkeys require about 75% of the calories of a pony of equal size,” Matthews explains. “Obesity is a killer for them.”

Davis agrees about the danger: “It’s pretty extraordinary what donkeys have evolved to survive on,” he says. “The biggest problem in developed countries is that it’s really difficult to find feed that’s fibrous enough, and it has to be less digestible than the stuff that we feed horses. Because otherwise, donkeys just get too many calories.

“We like to say donkeys are not small horses with big ears,” he adds. “But I think it’s safe to say that donkeys are small horses with big ears with metabolic syndrome. Their system is geared just like a horse with metabolic syndrome. They’re relatively insulin-resistant, and they’re just super easy keepers.”

Add to donkeys’ metabolic efficiency their indulgent, well-meaning owners, and you have a recipe for essentially killing them with kindness. “People absolutely love their donkeys,” says Cretney, “We’ve had people come in and say, ‘They have a pizza every Tuesday…’ and you have to explain to them that that’s very bad.”

Both Davis and Matthews cite The Donkey Sanctuary’s recommendation of straw as a good feed for donkeys.

“Oat and barley straw are preferable,” Davis says. “You can also use wheat straw, but it’s important to make sure that the straw is combined enough that there’s not a lot of grain left in it. Or various types of grasses, but they have to be grasses that are mature and lower in nonstructural carbohydrates (including sugars and starches). That’s the hard part.”

Matthews says most of the health problems donkeys in developed countries face are rooted in obesity, especially hyperlipemia. Hyperlipemia is a potentially deadly condition characterized by elevated fat concentrations in the bloodstream during times of stress and sudden weight loss/food deprivation. And because of this condition, the weight loss process for an obese donkey is actually a more complex and potentially dangerous process than weight gain in a malnourished one.

Underweight donkeys tend to “perk up and gain condition fairly quickly,” Cretney says, if approached in a stepwise, thoughtful fashion to avoid causing metabolic illness. But getting an obese donkey to trim down is another story.

“It’s incredibly difficult because of the hyperlipemia—you can’t just change their diet,” she explains. “It takes a really long time to get a donkey to lose weight—years to get it down to the right level.”

Cretney says that at The Donkey Sanctuary, overweight donkeys have extremely limited strip grazing (using movable fencing to limit a grazing area), and the donkeys’ grooms monitor the animals closely to ensure they don’t develop obesity-associated health conditions.

“If they’re young and healthy but just happen to be obese, we’d encourage them to exercise more—strip grazing doesn’t have to be just one line in a paddock, it can be more of a maze so they’re having to travel to get in and out,” she adds. “It takes such careful monitoring—you can’t go too aggressive on it. You’ve got to be very patient.”

Another obesity-related health issue donkeys develop is laminitis, Matthews says. Laminitis is a devastating hoof disease caused by an inflammation of the horse’s laminae—interlocking leaflike tissues attaching the hoof to the coffin bone—and a condition that can be difficult to recognize in our long-eared friends.

“Donkeys have sort of a different foot structure than horses have; quite often it isn’t recognized until you have really severe laminitis,” Davis says. “And then remembering that they have a metabolic makeup that’s similar to a horse with equine metabolic syndrome, given certain kinds of food, they’re prone to laminitis.”

Vincent and Cretney agree.

“One of the problems in this country (and in other developed nations) is that it’s just such rich pickings for them,” Vincent says. “Laminitis is a big issue. Strip grazing and controlled diets are really important.

“We get a lot of donkeys coming in as a condition score 4 or 5 (on a 5-point scale often used in the U.K.), which is very high for a donkey. They should be 3s. Obesity is an issue because people just overfeed them. Owners love to give them treats like Polo mints (Americans, think Wint-O-Green Life Saver for a rough equivalent) and ginger biscuits and carrots, but they don’t actually need it!”

Matters of the Mind: Stubborn or Simply Stumped?

The way donkeys behave and learn leads to another important welfare issue in developed countries, Davis says.

“Most people who deal with donkeys in this country got their start with horses, and donkeys have a very different psychology,” he explains.

They show pain and anxiety differently than horses, Davis says, and they have different responses to handling and training techniques. “And, as a result, they tend to get a reputation for stubbornness.”

Matthews agrees: “They are not stubborn, but their flight response is opposite of a horse. When presented with something new or scary, they will tend to freeze up while assessing it. There is a lot going on in their little brain, but it is less obvious to us.”

In other words, donkeys might be a little like a person who listens, processes, and then responds, rather than one who acts without hesitation.

Davis adds, “They’re such easy animals to work with, but they’re not horses.”

He believes the lack of understanding of donkey psychology and behavior is partially to blame for the growing number of unwanted donkeys in the United States.

Why Are Donkeys Being Abandoned?

“Peaceful Valley Donkey Rescue, in San Angelo, Texas, has something like 3,000 donkeys that they’ve rescued and they’re trying to find homes for,” Davis says. “And this happens all the time, because people get donkeys, and they expect them to be horses; they don’t understand and relate to the donkeys, they lose interest in them or they have a health problem, and they become unwanted.

“Donkeys are very, very hardy animals, and they live a long time,” he adds. “So they’re going to be around for a while. And, as a result, you end up with all these unwanted donkeys.”

This isn’t solely a U.S. problem. The U.K. and Ireland are also dealing with large numbers of unwanted donkeys. The donkeys’ dropping—or nonexistent—financial worth is a major cause of abandonments across the pond, Vincent says. And whereas U.S. owners can easily list their donkeys for sale, things in the U.K. are a bit more complicated.

“Their value has dropped to nothing,” Vincent says. “To sell a donkey in the U.K. or Ireland, you have to have a passport for each animal. Donkeys often don’t have them, and the passport costs more than the donkey’s worth. (In the meantime) owners aren’t bothering with hoof care because that’s £20 (around $31) a visit, and donkeys are not even worth £20 at the moment.”

Lingering post-recession challenges have caused people to lose jobs and homes and the land on which to keep donkeys. “Or, their marriage has split up, and the donkey is one of the things people don’t keep,” says Cretney.

Vincent recalls a recent case in which an owner sent their donkeys to the abattoir (slaughterhouse) because they didn’t want them anymore. “The abattoir rang us and said, ‘Do you think you could take them? They’re so young and healthy … there’s nothing wrong with them.’ And we did.”

Aside from processing for human consumption in some parts of the world, and with no legal options for selling donkeys without passports in the U.K. and Ireland and a limited market for them in other locations, some owners simply abandon or surrender their donkeys when they become unwanted. Other donkeys find themselves neglected, like Laurel and Hardy, two of The Donkey Sanctuary’s recent rescue cases.

“We found them shut in a stable in their own feces with no food, no water … they were in really horrendous conditions,” Vincent says. “We think they’d been shut in for about six months.

“Laurel, the gray one, had clumps of hair just falling off with red, raw skin underneath. They were covered in lice, their feet were long, they were both stallions, and they were really fed-up donkeys—really miserable.”

After arriving at the Sidmouth farm, the two were gelded and began their rehabilitation process. A farrier began addressing the pair’s hoof problems; they slowly gained back the weight they’d lost, and their coats grew in sleek and thick.

“It was just brilliant,” Vincent says with a smile. “Literally day by day you’d see a difference. And now, they’re just unrecognizable. You would not know that they came in such a state.”

Laurel and Hardy still reside at The Donkey Sanctuary, where they greet visitors on a daily basis and serve as continual reminders of the organization’s mission.

The Light at Tunnel’s End

By acknowledging and addressing the rampant welfare issues, the truth is our two donkeys’ lives can look a whole lot different: As the sun sets on another day in that small village, the owner of the slight, skinny donkey brings the animal in his family’s hut for the first time to share a meal of straw and a small pail of water with the cattle. His wounds will begin to heal, due to the better-fitting, more appropriately padded harness the owner has acquired. After attending a community-wide event, the owner learned that by investing a little more time, money, and consideration into his donkey’s health and welfare, the animal will become more productive. And the next morning the donkey greets his owner with perked ears for the first time.

Meanwhile, in the heart of the horse community, that Thelwell-esque donkey is slowly shedding pounds, thanks to the new drylot his owner created and the strict diet he’s consuming. And his feet, while still sore from time to time, are becoming less painful. After a serious discussion with her veterinarian, the owner realized that she’d inadvertently put her donkey on a dangerous path, and she acted quickly to rectify the situation. When she brings straw to her donkey several times each day, she’s always greeted with an excited bray of a healthy animal that’s no longer at death’s door.

Two very similar donkeys with two very different problems are on the path to better health and welfare.

Slowly but surely, the health and welfare of donkeys around the world are improving as a result of owner education. Despite the advances, there is still work to be done. But as long as there’s a donkey in need of help, individuals and organizations will be ready to provide assistance.

Credits

Erica Larson

Erica Larson is the news editor of The Horse and TheHorse.com. A Massachusetts native, she grew up in the saddle and has dabbled in a variety of disciplines including foxhunting and mounted games. Prior to her job at The Horse, Erica was a groom for a four-star eventer. Currently, Erica competes in three-day eventing with her off-the-track Thoroughbred, Dorado.

- Editor-in-Chief: Stephanie L. Church

- Designer: Kimberly Reeves

- Editorial Team: Michelle Anderson

Alexandra Beckstett - Multimedia Producer: Scott Tracy

- Publisher: Marla Bickel