Intensive Care for Equine Veterinarians

Equine veterinarians face a slew of stresses, ranging from work-life balance struggles and concerns about getting injured to compassion fatigue and moral stress. Find out why the practitioners caring for our horses also need care.

By Stephanie L. Church

Dr. Margo Macpherson

Margo Macpherson, DVM, MS, Dipl. ACT, is a professor in Large Animal Clinical Science at the university’s College of Veterinary Medicine, in Gainesville, and past president of the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP).

Sometimes Dr. Margo Macpherson needs a break from the day’s pressures of teaching, meeting, handling phone calls, responding to emails, troubleshooting tough cases.

The equine reproduction specialist retreats to the University of Florida’s teaching herd, watching them calmly munch grass and meander through their day.

“It makes me feel better,” she says. “That’s what being around horses does for me. That quiet presence, you know? That nuzzling, the look, the kindness in their eye, just feeling their hair under your fingers. All that can really calm me down. Smelling them, it’s a big trigger for me.”

When you see your horse’s veterinarian, it might just be for an hour at a time for a wellness check, lameness exam, or emergency. You review findings and care instructions with him or her and carry on with the day—good, bad, or indifferent, depending on the nature of the case.

Facebook and other social media platforms aside, we might not get a glimpse of the other 166 hours in our vet’s week and how those are filled … whether emotions run high or low or whether there’s time for exercise or an unrushed meal shared with family. But we know horses live their lives 24/7, in sickness and in health, so it’s safe to assume vets’ hours likely reflect those around-the-clock ups and downs.

Every individual manages pressures stemming from work, family, finances, personal interactions, and countless other sources. Veterinarians attest that the stresses they face can make the vocation rewarding yet harrowing. The simple fact they bear witness daily to the powerful bond between human and horse dictates that.

Several equine practitioners and members of the veterinary community have weighed in on these stresses, their causes, and the ways they and the profession are managing them.

How the AAEP Past President Strikes Work-Life Balance

Dr. Margo Macpherson calls herself “a bona fide stress monster,” but has found success in striking a work-life balance by strategically planning out her days. Read about how she does it here: TheHorse.com/159601.

CREDIT: Courtesy Dr. Margo Macpherson

Dr. Amy Grice

Amy Grice, VMD, MBA, is a 25-year veteran of equine practice who now consults with and advises veterinarians, practice owners, and industry partners on a wide variety of projects and challenges from her base in Virginia City, Montana.

Charlotte Hansen

Charlotte Hansen, MS, is an equine economist at the American Veterinary Medical Association, in Schaumburg, Illinois.

Balancing Work & Life

Pressures hit the newly minted veterinarian early, says Dr. Amy Grice, who, after 25 years of equine practice, consults with veterinarians on business from her base in Virginia City, Montana. “I certainly think that student debt load is definitely at the top of the list of stressors, but another stressor for those younger veterinarians is simply learning to balance their desire to be accepted by clients as a new veterinarian, a new associate in the practice, while remaining able to have appropriate boundaries.

“If they’re lucky enough to have landed at a practice that really practices good work-life balance and tries to make time for everyone who is on the practice team to have a life outside of practice … and in their enthusiasm to (build a client base) provide their cell phone number and answer it all times of night … they may find it hard to back up the train,” she adds.

A few years after their clients begin to expect round-the-clock accessibility, Grice says many of these practitioners start families. “All of the sudden they have a lot of clients, they’ve trained them in a certain way … they start feeling the pinch, not having enough time, and it’s harder to go back.”

Lack of work-life balance can inevitably shift to burnout, says Dr. Rob Franklin, a partner at three Texas veterinary practices and managing partner at Full Bucket, a business with a strong charity component, in Dennis. He says there’s stress no matter your station in the profession.

“I guess I have many perspectives: business owner, employee, entrepreneur, clinician, board member, volunteer, and equitarian,” says Franklin, the latter role involving volunteering time to help care for horses in remote areas lacking veterinary resources. “Those ‘hats’ definitely allow me the opportunity to test many of my biases with the different colleagues I interact with.

“Eliminating debt certainly was the key to me developing meaning to my life and career and choosing how I would spend my time. I used to think work-life balance meant ‘work hard, play hard.’ I did lots of that and continue to enjoy work and play. But that’s not balance. Balance is getting to do what is fulfilling to you in your work and personal life. When you are in debt, you don’t have the liberty to follow your dreams. You are literally a slave to it.

“Burnout was the biggest for me 10 years ago after internship and residency and saying yes to everybody and everything in order to grow my business,” he says. “Now, I get stressed about human resource issues. Keeping your team motivated, engaged, and feeling fulfilled is a real challenge.”

Charlotte Hansen is an equine economist at the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), in Schaumburg, Illinois. “Based on AVMA data, burnout scores (using the ProQOL self-score method) measure just one aspect of mental health—how one feels about their work—and does not include the many other dimensions that constitute the full spectrum of mental health,” she says. “While on average, burnout scores were in the low normal range for equine practitioners, there are of course other reasons that affect mental health that are not measured and could play a part in burnout. There is reason to believe that burnout is a cause of equine practitioner attrition, but more research is needed.”

Dr. Rob Franklin

Rob Franklin, DVM, Dipl. ACVIM, is a partner at three Texas veterinary practices (Guardia Equine Sports Medicine, in Houston, Fredericksburg Equine Veterinary Services, and Stephenville Equine Sports Medicine) and managing partner at Full Bucket, a business with a strong charity component, in Dennis, Texas.

CREDIT: Paula da Silva/ arnd.nl

Source: 2016 AVMA/ AAEP Survey

Feeling "Trapped"

Dr. Jeremiah Easley, after completing an internship and a surgical residency, is co-director of the Preclinical Surgical Research Laboratory at Colorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, in Fort Collins. He considers himself fortunate to have trained and worked in equine practices and universities that value work-life balance and foster healthy working relationships. However, he says he knows classmates and colleagues who have been less fortunate.

Easley explains that many individuals in the profession have directed their lives toward becoming veterinarians, “and they have in their mind a particular dream or fantasy about what veterinary medicine’s going to be like.” If a veterinarian joins a new practice and is not able to take part in important change or do something they’re passionate about doing, it can be very stressful.

In such a situation, “I think not only are you trapped in your position, but you’re trapped by debt,” he says. “You’ve been driven to make it to veterinary school, the next goal is to acquire a DVM and then put your knowledge to work. At that point you may land in a position where you feel like your hands are tied and/or you are unable to practice veterinary medicine the way you may want or have been trained. The dilemma becomes, ‘Well, I’d like to leave, but I owe $300,000 to the government, how can this work?’ That can be extremely stressful on veterinarians.”

As notoriously goal-driven people, vets, he says, work persistently and might stay in a position far too long, putting up with difficult working conditions because they have a family to care for and student loan payments to make. They might be fearful about what the next place will hold.

Dr. Jen Brandt is director of wellbeing and diversity initiatives at the AVMA, and interacts with practitioners daily. She says in some cases a veterinarian might feel he or she can’t leave a practice “because there’s a fear they might be blackballed, to some extent, and may not then have the same opportunities. If for whatever reason you’re not satisfied with where you’re working, it’s not like there’s necessarily another practice up the road in most places (as the case might be with small animal medicine). So you’d be looking at … relocating your family and starting a new client base.

“So, some will say that they experience stress from feeling trapped,” she adds.

Dr. Jeremiah Easley

Jeremiah Easley, DVM, Dipl. ACVS, is co-director of the Preclinical Surgical Research Laboratory at Colorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, in Fort Collins.

Dr. Jen Brandt

Jen Brandt, LISW-S, PhD, is director of wellbeing and diversity initiatives at the American Veterinary Medical Association.

CREDIT: iStock

“There is a new paradigm that is coming, one veterinarian at a time, that understands that we can provide really excellent service without sacrificing lives on the altar of veterinary medicine.”

Dr. Amy Grice

Source: 2016 AVMA/ AAEP Survey

Changing Attitudes About Work Ethic

Historically, vets have worked very hard. But overall, the newer arrivals to the profession, as they ponder their futures, want to have more of that work-life balance. This is a stark contrast to what many veteran practitioners experienced early in their careers or expect as supervisors.

“I think it’s difficult sometimes on the equine side,” says Grice. “We have a very strong ethos and identity as the tough equine vet that has no boundaries, works all the time, works till they tip over in their boots, and if you aren’t that person (it can be easy to feel) that you don’t belong, that you’re not worthy of being a part of the club. And I’ve talked to many young women who have felt like they needed to leave equine practice because they were tired of working 60 and 70 hours a week and feeling like they were a slacker and that they weren’t doing a good enough job.

“So, that’s on us to change that, and I feel very optimistic with the young veterinarians I meet in my groups (of young practitioners I mentor) that there is a new paradigm that is coming, one veterinarian at a time, that understands that we can provide really excellent service without sacrificing lives on the altar of veterinary medicine.”

Macpherson says it’s important to consider other generational perspectives, as well. She sees many young equine veterinarians trying hard to achieve work-life balance but also be professionally successful in a world that doesn’t completely understand that concept. The key is taking the time to understand all sides.

“Often we hear the story about the established veterinarian whose expectations are out of alignment with those of their younger associates,” she says. “It’s also the other way around. There often is a set of expectations that our younger veterinarians come in with, as well, that may not take into account what has gone into growing that practice and what the stresses are for that individual.

“I even see it in a training situation where we have residents and students that probably are rightfully irritated when I’m not available to help them with something or do something … not understanding that my workday doesn’t start then, out there in the barn. My workday goes on well beyond that. And, so, it’s also just taking into account that everybody’s life has more dimension to it than we really see.”

Easley reflects on what ideal internship and residency scenarios look like. He considers himself lucky to have trained under Macpherson’s husband, John Peloso, DVM, MS, Dipl. ACVS, and under Franklin, who understand and appreciate good work-life balance. “Their philosophy was very much, ‘You guys work together to get the job done. Your internship doesn’t have to be a nightmare,” he says.

“As long as the team was getting along and helping each other out, that meant that if we worked better together and got it done earlier, we’d go enjoy dinner somewhere as a team. Let’s do that; let’s not stick to ourselves with every man for himself.”

Finding Balance Amid the Day-to-Day Rigors of Vet Practice

Nigel Marsh, TED Talk Alum, shared advice for veterinarians on achieving the often-elusive balance between careers and personal lives at the 2017 American Association of Equine Practitioners’ Annual Convention. Read about his take-homes at TheHorse.com/13711.

CREDIT: Robo Hendrickson

Source: 2016 AVMA/ AAEP Survey

The Possibility of Getting Injured

The patients veterinarians work with day in and day out, some of which might be experiencing pain, compromised soundness, or balance issues, pose real injury risks. Others might simply be resistant to procedures or handling.

Hansen points out that in a joint survey conducted with AVMA and AAEP in 2016, nearly four-fifths of equine practitioners reported that they’d been injured while on the job.

About 40% of AAEP members are solo practitioners, says Grice. “They have to go back to work (if they get injured) because there’s nobody else to make money. Some will lose their clients; they’ll lose everything they worked so hard for, and so that concern about viability of their practice if they get injured is often in the backs of their minds.

“The thing is, while you’re not serving your clients, somebody else is,” she says, noting that she’s found some veterinarians going back to work two weeks after a head injury or directly after an extended hospital stay.

But while there is “tremendous, back-biting competition” in some horse-centric areas of the country, Grice says that’s not typically the case elsewhere. Rather, most surrounding vets “just come on in and take care of their injured colleague’s clients and do their own calls and take good care of them and then hand them back. There is still a lot of collegiality in many places. The more veterinarians competing for a shrinking pool (of horse-owning clients), the worse that collegiality seems to be, but I guess it’s human nature.”

Number of Injuries Incurred Which Caused Missed Work (n=415)

Source: 2016 AVMA/ AAEP Survey

Jen Brandt, LISW-S, PhD, is director of wellbeing and diversity initiatives at the American Veterinary Medical Association.

CREDIT: iStock

Mindfulness Training Could Help Combat ‘Compassion Fatigue’

At the 2015 American Association of Equine Practitioners Convention, Daniel Siegel, MD, clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Medicine, described how improving resiliency can equip veterinarians to combat distress and burnout, and help them lead healthier lives. Read about this at

TheHorse.com/16910.

Compassion Fatigue & Moral Stress

Veterinarians must also manage stress that comes with making sad and/or difficult decisions on a regular basis. Many refer to this as compassion fatigue.

“I think all veterinarians have those times when they just happen to run into a week where they’ve just had some really, really hard cases,” says Grice. “I think about a week that I had one year when we had a particularly awful strain of Potomac (horse fever), and … you would do every single thing you knew how to do, and you had to euthanize them anyway. In one single week I (lost) one of my own horses and two client horses.

“I don’t know if that’s compassion fatigue or it’s simply just way too sad when you do everything you know and it doesn’t work,” she says. “Or you get a string of broken legs. It can’t help but get to you when you’re a witness to such sadness and the breaking of the human-animal bond, which can be very, very strong with horses.”

However, “I don’t sense that veterinarians get tired of being compassionate,” she says. “Especially equine veterinarians, because they’re wired that they love horses and the people that love horses. So, they do this hard, dangerous job because they love it.”

Brandt agrees. Although compassion fatigue has been a common conversation in the industry (in fact, it was the 2015 AAEP Convention keynote subject), when she talks to veterinarians, “it can be more about the moral and ethical stress that they have, where they may be asked to do something by a client that is difficult based on the other options available.”

Whether it’s to administer a drug that might be in violation of competition rules or perform a procedure such as tail blocking—which many associations such as the AAEP condemn and multiple jurisdictions prohibit because it can cause serious complications and injection site infections—such requests put veterinarians in stressful situations. Then there are the cases where the choice is between treatment and euthanasia.

“So, if the decision has to be made by the client because of finances, which we understand,” says Brandt, “for a veterinarian who has to face that day in and day out, having to make decisions about medical care based on the client’s finances can be difficult. More and more clients are facing financial stress, so that transfers to the veterinarian.”

“Having to make decisions about medical care based on the client’s finances can be difficult. More and more clients are facing financial stress, so that transfers to the veterinarian.”

Dr. Jen Brandt

CREDIT: iStock

A Shifting Industry, Demographic

Grice says that in the 1990s and early 2000s, which she calls the go-go years, equine veterinary practices were growing quickly, and it was a matter of whether veterinarians could get all the work done every day. Today, she says, fewer people own horses, and they tend to be a wealthier demographic overall. Veterinarians must determine how to provide a lot of value to a limited number of clients, to provide the best possible care for their horses … without always being on call.

One approach she says vet practices are taking is building loyalty to the practice rather than individual veterinarians within it. “Those are the practices that can have a four-day week,” she says, “because no matter which doctor comes out—and (the client) may prefer a particular doctor—they know that they will receive very good care and … the ideas, the type of care, the treatment will be similar.”

She gives the example of Carol Sabo, DVM, founder and manager of Haymarket Veterinary Service in Virginia. “She has a number of young women working for her,” says Grice. “She set up her veterinary trucks basically identically, and the telephone and the veterinary assistant or technician belongs to the truck, not to the doctor, and then they rotate days.

“The doctors are not interchangeable,” she continues. “Obviously, they are human beings and they have their strengths and their weaknesses, but things are set up so the client has a seamless experience; no matter who comes out, (they know) they’re going to get a good, competent, caring, compassionate veterinarian.

“But clients have to accept that,” she adds, and not demand favorites from among the group.

CREDIT: iStock

Support for Veterinarians Seeking Work-Life Balance

Equine veterinarians in the U.K. have launched an initiative called MumsVet to educate parents—both moms and dads—and employers/practice owners about issues surrounding work-life balance and pregnancy. Read about this at TheHorse.com/159604. | Photo: Courtesy Dr. Vicki Nicholls

Other Stresses

Brandt says in her conversations with vets she’s heard about other important stressors, some specific to women.

“Certainly what females report in the workplace is that they are disproportionately impacted by issues of sexual harassment or other types of harassment in the workplaces, often from fellow colleagues, but also not infrequently from clients. This can impact them, as far as feeling safe in the workplace and having equal access to opportunities,” she says.

“Many will say (being female) even impacts the interview questions that they get—like ‘Are you ever going to plan to have a child, and how would you handle work if you’re pregnant?’ when that’s an illegal interview question,” she adds. Veterinarians who are moms often feel pulled to come back to work sooner than advisable.

Parallel service providers also challenge equine veterinarians, says Hansen. These are “the nonveterinarians that are competing with the veterinarians for services—equine dentistry, integrative therapies, show circuit (services), internet and traveling pharmacies, etc.”

Still other pressures come in the virtual world, where criticism abounds 24/7.

“An increasing stress seems to be related to social media and the impact that a Yelp review may have,” says Brandt, “particularly if the client hasn’t made any attempt to speak with the veterinarian to address the concerns and, instead, takes it to a public forum immediately.”

Word travels fast on Facebook and other platforms, where one negative comment can gain momentum, hurting the reputation and, therefore, the business of a vet or an entire practice. Knowing the potential of these media can cause veterinarians considerable stress.

Brandt also cites isolation, as many veterinarians work in small practices or solo and don’t necessarily have the team support that might be the norm across other medical professions.

Macpherson feels isolation even happens in a team setting. “Veterinarians are made up largely of a group of introverts and, so, that results in either not extending ourselves to people that we think might be in need or not asking for help, and a big part of that is establishing trust and safety (for talking about these issues) in the workplace,” she says. “And … we’re trying to work on that, especially at the AAEP. That’s a marathon, not a sprint.”

Practitioners attending the 2018 AAEP convention, held in December in San Francisco had the opportunity to learn about yet another important issue. “Veterinarians are not insulated from the traps of chemical addiction,” says Franklin. “In fact, having access to many controlled substances can make this problem more of an issue than with other trades or professions.”

Session presenters included top clinicians on addiction, a recovering addict and practice owner, and a Drug Enforcement Administration agent.

Dr. Margo Macpherson has learned to juggle her job as a veterinary professor with family time and personal commitments. | Photo: Courtesy AAEP

CREDIT: iStock

We want to make sure that when we graduate students, they’re well-rounded and not just on the science of medicine but also on the art and practice of the medicine and self-care.

Dr. Jen Brandt

Prioritizing Veterinary Wellness

“There’s been an incredible shift, I think, and awareness of well-being, really in the last decade,” says Brandt, who in her former role served as director of Student Services at The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine. “It feels like all hands on deck.”

She says her team is dedicated to bringing well-being initiatives and awareness to individuals and into practices and organizations, as well as focusing on diversity and inclusion as key elements of well-being.

Some of those initiatives are being woven in even before the white coat ceremony, the ritual marking the beginning of a vet student’s education.

“Veterinary colleges are really committed to addressing well-being, and so I believe the majority now have either an embedded on-site mental health professional that works directly with the program or at least a coordinated effort with a counseling program that may be located on campus where they can quickly refer students,” Brandt says.

“And more and more courses are being offered within the curriculum, whether it’s core or elective, that relate to self-care, such as boundary-setting, and transforming conflict— a lot of the (skills) that impact well-being throughout a career. We want to make sure that when we graduate students, they’re well-rounded and not just on the science of medicine but also on the art and practice of the medicine and self-care. The AAVMC (American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges) is really involved with supporting those efforts.”

A few years ago Brandt helped start a veterinary mental health professionals group made up of counselors and social workers specializing in veterinary medicine. “Many of the individuals in the group have been active in the profession for anywhere from a decade up to two decades,” she says. “I find that remarkable that there’s this specialized expertise out there. At the AVMA specifically, we have an amazing student initiative team who’s going out there with a ‘boots on the ground’ approach, working with the students to hear their concerns and also learn what’s working well.”

And for the veterinarians already in practice, the AVMA offers a variety of services, from counseling to free cyberbullying assistance for members.

Prevention is key, says Brandt, noting that the gap isn’t so much in the programs offered, but in being sure that the veterinarians are accessing the programs before they’re in crisis.

Even beyond AVMA, Franklin says most veterinary organizations are trying to be sensitive to their members’ personal well-being needs, as well as their education or political representation.

The AAEP is weaving a heavy stitch of what we call Healthy Practice into everything we do,” he says. “It’s not really a box to check or a session to attend but, more so, a culture you create when you are extremely intentional about authentically caring for, supporting, and engaging with your colleagues about their well-being.”

Horse Owner Empathy and Our Equine Veterinarians

Issues of mental health, well-being, and suicide among vets are important ones that veterinary organizations worldwide have made a priority. TheHorse.com/160433. | Photo: Anne M. Eberhardt/The Horse

What the Numbers Say

For her job Hansen researches and analyzes the economics of the veterinary profession and, with her colleagues, generates actionable insights through reports, webinars, blogs, articles, presentations, and other avenues.

She has combed through data from a joint survey conducted with AVMA and the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) in 2016. “When we look at the AAEP membership data, the attrition rates for those that were leaving before five years of being a member in the AAEP were used as a proxy for those leaving the equine profession,” she says. “It doesn’t necessarily mean they’re leaving the profession as a whole, just leaving equine veterinary medicine. And what we see is an increasing trend in new veterinarians after graduation not renewing their AAEP memberships after five years.

Distribution of Equine Respondents Leaving the Profession by Time Frame of Departure (n=89)

Distribution of Equine Respondents Who Reported Leaving the Equine Profession Within 5 Years of Graduation, by Graduation Year

“If we take a look at the survey data,” she adds, “67.4% of survey respondents who are currently not working in equine medicine left between zero and five years of practicing equine medicine, and almost three-quarters of the respondents reported graduating on or after 2000.”

She notes that average equine starting salaries are still lower on average than in other areas of veterinary medicine, and that the gender distribution over the past decade or two has shifted to more females entering the veterinary profession than males.

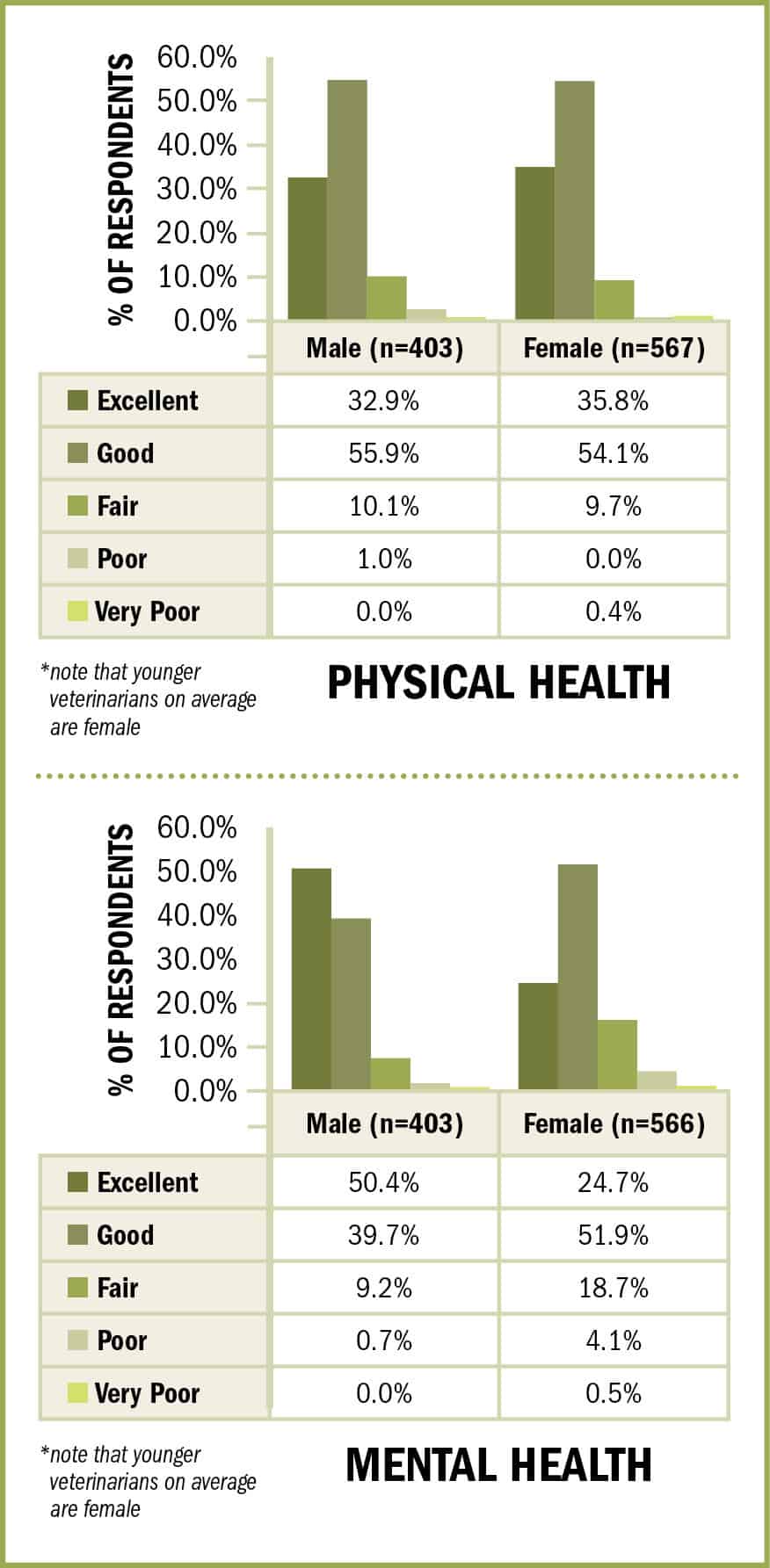

“When we look at the high average student debt that new veterinarians are facing, and we look at the average equine starting salaries for equine practitioners, and they’re on average lower than those in companion animals and also in all private practice, this is a huge realization to be facing right after graduation,” she says. “And if we look at the data, we see that a lot of younger veterinarians who, keep in mind, the majority are female, report having a lower excellent mental health than those that are males .

“Is that mental health related to the high debt, the lower starting salaries, a lot of the other issues that the equine practitioner is facing in the profession?” Hansen poses. An economic analysis on burnout from the AVMA/AAEP survey reveals that on average, dissatisfaction with current employment, not feeling that education prepared the equine vet well, working more hours, and currently owing on educational debt were just a few of the significant factors affecting burnout.

“Now, if we look at physical health conditions, we see that male owners and associates are reporting a less percent of excellent health compared to female owners and associates.”

Other findings:

- The longer the respondent was practicing veterinary medicine, the lower the odds or likelihood he or she left equine medicine within five years.

- The odds of having left the equine profession within five years after graduating were higher for respondents who completed an internship than those who didn’t.

- The odds of having left the equine profession within five years after graduating were higher for those respondents currently in public practice (e.g., industry, academia, consulting, research) than for those in private.

“We have to keep in mind when we look at the survey numbers that the shift in gender across graduation years has changed, with more females entering the profession right now than males,” she says. “In the equine survey the average age for equine (veterinarian) males was 55, and the average years of experience was 29 (more than a quarter of males had more than 40 years of experience, compared to less than 1% of females). For females, the average (age) was 39 years, and the mean years of experience was 12 (median years of experience was nine).”

Changing Gender Distribution in the Equine Profession

Average age of male equine respondents

54.9 years

(median of 58 years)

Mean years of experience for male equine respondents

29 Years

Average age of female equine respondents

39.2 years

(median of 35 years)

Mean years of experience for female equine respondents

12.3 years

Source: 2016 AVMA/ AAEP Survey

The onus is on the professional to intentionally create healthy boundaries in their practice. Sometimes that starts with a conversation with ourselves that says, ‘I can’t be all things, to all people, all the time.’

Dr. Rob Franklin

Walking Forward

Now that we know what our veterinarians are dealing with, how do we respond?

“Ultimately, the horse owner is dealing with their own issues and the issues of their horse,” says Franklin. “If they have an emergency, then they should be able to seek emergency care without feeling like they are being a burden. The onus is on the professional to intentionally create healthy boundaries in their practice. Sometimes that starts with a conversation with ourselves that says, ‘I can’t be all things, to all people, all the time.’ That’s honest and allows us to gain some perspective on where we are spending our time and resources, so that we can find ways to provide care and coverage for our clients without always being the one to do it.”

While we don’t need to take on our vets’ struggles, we can remember them as we interact. “I think it’s important that clients understand that veterinarians are people, too, and they come to veterinary medicine because they love the horse and they want to do their very best,” says Grice. “But they’re human.”

In other words, recognize that while your veterinarian might seem like a super human, he or she experiences stress and goes home to many of the same challenges or concerns that you do.

Macpherson reflects: “I absolutely love what I do, and I feel so proud and so happy and so satisfied to be an equine veterinarian, in all capacities. I’m not going to lie, there are the bumps. But overall, to be able to say that I love my job is a great, great thing, and I would love for many, many people below me, agewise, to have the same opportunity, and the best way to do that is to facilitate it and make some changes.”

“Globally, if we can come back to that mantra—be kind,” says Brandt. “We’re doing the best we can. (It’s important that we have) some tolerance, compassion, empathy, and seeking to understand other perspectives as part of how we routinely interact with those around us.”

CREDIT: Courtesy Robo Hendrickson

How You Can Help

Equine practitioners interviewed for this article were adamant that clients never bear the burdens of their veterinarians’ stresses. However, there’s one way you can help address the challenges at hand: Ensure your horses are well-trained for handling and veterinary procedures. (Find a useful article about this at TheHorse.com/115889.)

“It can be hard to say no to a client,” says Dr. Amy Grice, who consults with veterinarians and practices about running their businesses. “Maybe you have a solo practice and you need them as a client. Maybe their horse is misbehaving and making you feel a little afraid and you really want to sedate it, but they don’t really want you to. Will you put yourself in danger? Some of (the veterinarians) may, and they’ll get lucky a lot of the time. Then there’s going to be that time that they’re not lucky.”

Remember that horses are accustomed to their environments and their vocations, says Grice, but they’re not necessarily used to someone doing something noxious to them or injecting them. “So even the nicest horse that you could let your kid get on bareback with a halter and graze in the yard as chickens run around and cars and ATVs ride by is very different than that same horse having a hind-limb laceration sewed up,” says Grice.

“Keeping your veterinarian safe, so they can go home to their family, continue practicing, and pay their debts—that’s a place where clients could really help their veterinarians, particularly those that are in solo practice, but even in group practice, because every veterinarian is needed to get the work done,” she says.

Credits:

Stephanie L. Church is editor-in-chief of The Horse: Your Guide To Equine Health Care/ TheHorse.com. A 4-H and United States Pony Club (USPC) member, she grew up riding hunters and then eventing. She earned a B.A. in Journalism and Equestrian Studies from Averett University in Danville, Virginia, and joined The Horse team in 1999. She is a past-president of American Horse Publications and volunteers with the Lexington (Kentucky) Mounted Police Unit. Currently she trains her retired racehorse, It Happened Again, in dressage and eventing.

Editor-in-Chief/ Designer: Stephanie L. Church

Digital Producer/Designer: Jennifer Whittle

Digital Managing Editor: Michelle Anderson

Editorial Team: Alexandra Beckstett, Erica Larson

Illustrator: Brian Turner

Web Producer: Jennifer Whittle

Publisher: Marla Bickel