Understanding, Recognizing, and Managing Pain in Horses

Chronic musculoskeletal pain in horses can be managed

By Stacey Oke, DVM, MSc

Sponsored by:

Photo: Adobe Stock

There are times when a horse in pain—rolling, pawing, and sweating—is unmistakable. But signs of pain in a horse are often much more subtle. You might see a horse standing quietly in the stall, slightly shifting weight from one foot to the other, or the horse warming up for work, swishing his tail and pinning his ears back, delicately weighting stiff limbs in a short, choppy gait. These are the looks of horses showing signs of chronic pain, typically secondary to musculoskeletal conditions such as osteoarthritis (OA), long-standing ligament or tendon injuries, navicular syndrome (also called podotrochlosis or caudal heel pain), or even chronic laminitis.

“Many sport horses have chronic low-grade musculoskeletal pain that is often bilateral, affecting either both forelimbs or both hind limbs,” says Dr. Sue Dyson, an independent consultant based in the U.K. “It is therefore not seen as a conventional lameness but, rather, a shortening of step length and reduced suspension of the gaits. This is often insidious in onset and slowly progressive and frequently goes unrecognized. So even in otherwise well-managed horses the failure to recognize pain results in a potential welfare issue.”

While managing a horse with chronic pain typically isn’t as emotionally charged as caring for horses in acute pain, chronic pain is equally important.

Sue Dyson,VetMB, PhD,

graduated from the University of Cambridge in 1980. After an internship at the University of Pennsylvania and a year in private equine practice in Pennsylvania, Dyson returned to Great Britain to the Animal Health Trust, in Newmarket. She ran a clinical referral service for lameness and poor performance for 37 years. Dyson currently works as an independent consultant based in Suffolk, U.K., advising on performance aspects of equestrianism, drawing on her observations of many years as a hands-on horse person and veterinarian.

“In the face of discomfort, horses modify their gaits, reduce the range of motion of the thoracolumbosacral region, with resultant muscle dysfunction and atrophy, development of myofascial tension, and alteration of posture,” says Dyson. “All of these changes can result in the development of secondary sites of pain. Moreover, these horses become less trainable and less comfortable for a rider, which may result in the use of inappropriate training cues.”

What can we do for horses facing chronic musculoskeletal pain? No. 1 is timely recognition.

“As prey animals, horses innately try to hide signs of obvious lameness, but they do display behavioral signs of pain,” says Dyson. “Unfortunately, many of these behaviors have become normalized in the equine world, meaning it’s been accepted that there are grumpy, lazy, unwilling, or ‘stressy’ horses. These behaviors, however, should be recognized as abnormal and a reflection of how horses are trying to communicate with us.”

In this article we’ll have equine experts define and describe the different types of pain horses can experience, followed by a discussion of various management options for chronic pain, focusing on OA. Finally, we’ll provide suggestions for keeping horses being treated for chronic musculoskeletal pain moving comfortably. To combat OA long term we emphasize the importance of a multimodal approach to treating chronic musculoskeletal pain using intra-articular therapies, oral medications, topicals, and systemic drugs.

Photo: Adobe Stock

Understanding Pain in Horses

Merriam-Webster defines pain as “a localized or generalized unpleasant bodily sensation or complex of sensations that causes mild to severe physical discomfort and emotional distress and typically results from bodily disorder such as injury or disease.”

For those of us who have experienced real pain ourselves or witnessed a horse in pain, this definition might seem cold and distant … far from just unpleasant! It simply fails to adequately describe the excruciating nature of pain or the emotional toll it takes on its victims.

Further, this definition doesn’t address the different types of pain horses can experience.

NOCICEPTIVE PAIN

The traditional acute pain many of us think of is called nociceptive pain. This occurs when a noxious stimulus, such as extreme heat or cold, tearing, crushing, penetrating injuries, chemicals/toxins, and inflammation, triggers pain receptors in one part of the body. More specifically, horses can experience nociceptive pain after fracturing a bone; sustaining a penetrating injury or laceration or a tendon or ligament tear; or developing acute laminitis—inflammation in the sensitive layers of the hoof.

These stimulated pain receptors at the site of injury or inflammation in turn activate local (peripheral) sensory nerve fibers. Those sensory nerves start a signal, called an action potential, and transmit it to the spinal cord, then the brain. Different areas of the brain then perceive the details of the pain—where exactly the pain is located and how intense it is.

Some of the pain fibers can transmit the pain signal so quickly that animals withdraw from the painful stimulus before they even register how painful it was (e.g., touching an electric fence with their nose and reflexively leaping backward).

NEUROPATHIC PAIN

In this type of pain, damaged or dysfunctional nerves send abnormal signals to the brain, resulting in the horse perceiving pain.

INFLAMMATORY PAIN

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, e.g., phenylbutazone [Bute] or flunixin meglumine [Banamine]);

- Steroids (e.g., dexamethasone);

- Opiates/narcotics (e.g., morphine, hydromorphone, butorphanol);

- Alpha-2 agonists (α2, g., xylazine);

- Dissociative anesthetics (e.g., ketamine); and

- Local anesthetics such as lidocaine or bupivacaine.

Practitioners can administer these drugs by several systemic routes such as intravenously (IV), intramuscularly (IM), or subcutaneously (SC/SQ); intra-articularly (IA, into a joint); orally (per os, PO); via epidural injection (into the spinal canal but not the spinal cord itself); via regional perfusions; and topically/transdermally (through the skin).

“With improvements in management and veterinary care, we are seeing horses live longer lives and remain in work for more years than ever before,” says Dr. Harold C. McKenzie III of the Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine. “With these changes, the incidence of chronic pain is inevitably going to increase, making it essential that we find more effective ways of mitigating and managing pain in affected individuals. The need for long-term therapy makes it imperative that we identify therapeutic approaches to pain management that do not carry high levels of risk for complications. The multimodal approach is one of the key ways in which we can make progress in achieving this goal.”

Harold C. McKenzie III, DVM, MS, MSc (VetEd), FHEA, Dipl. ACVIM (LAIM),

is a professor of large animal medicine at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine in Blacksburg, Virginia. He received his DVM degree from the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine in 1990, completed an Equine Internal Medicine Residency at the Marion duPont Scott Equine Medical Center in Leesburg, Virgina, and received his MS degree from Virginia Tech in 1998. His research interests include veterinary education and various aspects of equine medicine, including pain management, critical care, and pharmacology. McKenzie has delivered more than 90 presentations at conferences and is the author or co-author of more than 50 refereed journal articles and 20 book chapters.

Photo: Adobe Stock

Pain in the Equine OA Setting

While researchers once thought osteoarthritis to be a disease restricted to the articular cartilage lining the ends of long bones inside joints, they now consider it a whole-joint disease. Specifically, inflammation within any of the joint tissues secondary to trauma (i.e., repeated concussion during exercise) can set off a cascade of molecular events that lead to:

- cartilage degradation

- inflammation, hyperplasia (abnormal increase in cell number), and hypertrophy (in size) of the inner lining of the joint, called the synovium

- joint capsule thickening or fibrosis

- bone changes, such as a hardening of the bone layer lying directly beneath the articular cartilage (i.e., subchondral sclerosis). In addition, bony growths called osteophytes can also form on the edges of bones near the joints.

Clinically, horses with arthritis could experience heat, pain, and swelling localized to one or more joints. However, some horses might not show overt clinical signs.

Osteoarthritis is the leading cause of lameness in horses, responsible for approximately 60% of all lameness cases (as cited by Aragona et al., 2024). The condition drives attrition and early retirement in horses and ultimately leads to welfare issues in severely affected individuals.

Some of the pain from OA is nociceptive, caused by loading the joint that stimulates the sensory pain fibers. As OA further progresses, it often leads to chronic pain that can trigger neuropathic conditions—where nerve damage worsens pain—or maladaptive changes, which are lasting nervous system changes that continue to cause discomfort even after the initial damage has subsided. More specifically, damage to neurons innervating the joint, causing pain independent of the joint pathology’s (disease or damage) severity, might occur (McKenzie et al., 2023; Eitner et al., 2017).

Before delving into how to treat OA-related pain, the first step is recognizing musculoskeletal discomfort in horses.

Photo: Adobe Stock

Spotting Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: Ridden Horse Pain Ethogram

The traditional pain scale veterinarians use in the United States for evaluating lameness in horses is the American Association of Equine Practitioners’ (AAEP) Lameness Scale, which allows them to subjectively grade horses on a scale from 0 (no lameness) to 5 (minimal weight-bearing).

This scale has its limitations. Notably, not all horses with OA show up with a hobbling gait. Instead, signs of pain can be quite subtle and, therefore, missed using this tool.

Therefore, equine veterinarians developed other approaches to more reliably identify musculoskeletal pain—even subtle pain due to mild OA. These include body-mounted inertial sensor systems (BMIS) and force-plate analysis. While useful, these latter techniques require specialized equipment that is not readily available or often too costly for daily use in equine practice. Further, the results with bilateral lameness—mentioned earlier, when the horse is lame in both limbs of a pair—might be misleading.

This is where pain scales could be useful. Practitioners have several available for clinical use, including the horse grimace scale seen below, the Equine Utrecht University scale of facial assessment of pain (EQUUS-FAP), the equine pain scale (EPS), the Equine Brief Pain Inventory (EBPI), the composite orthopedic pain scale, and the horse chronic pain scale.

However, Dyson says these pain scales were designed for use in horses at rest, not during exercise.

“Further, these scales have shown limited efficacy in the identification of chronic musculoskeletal pain so far,” she adds.

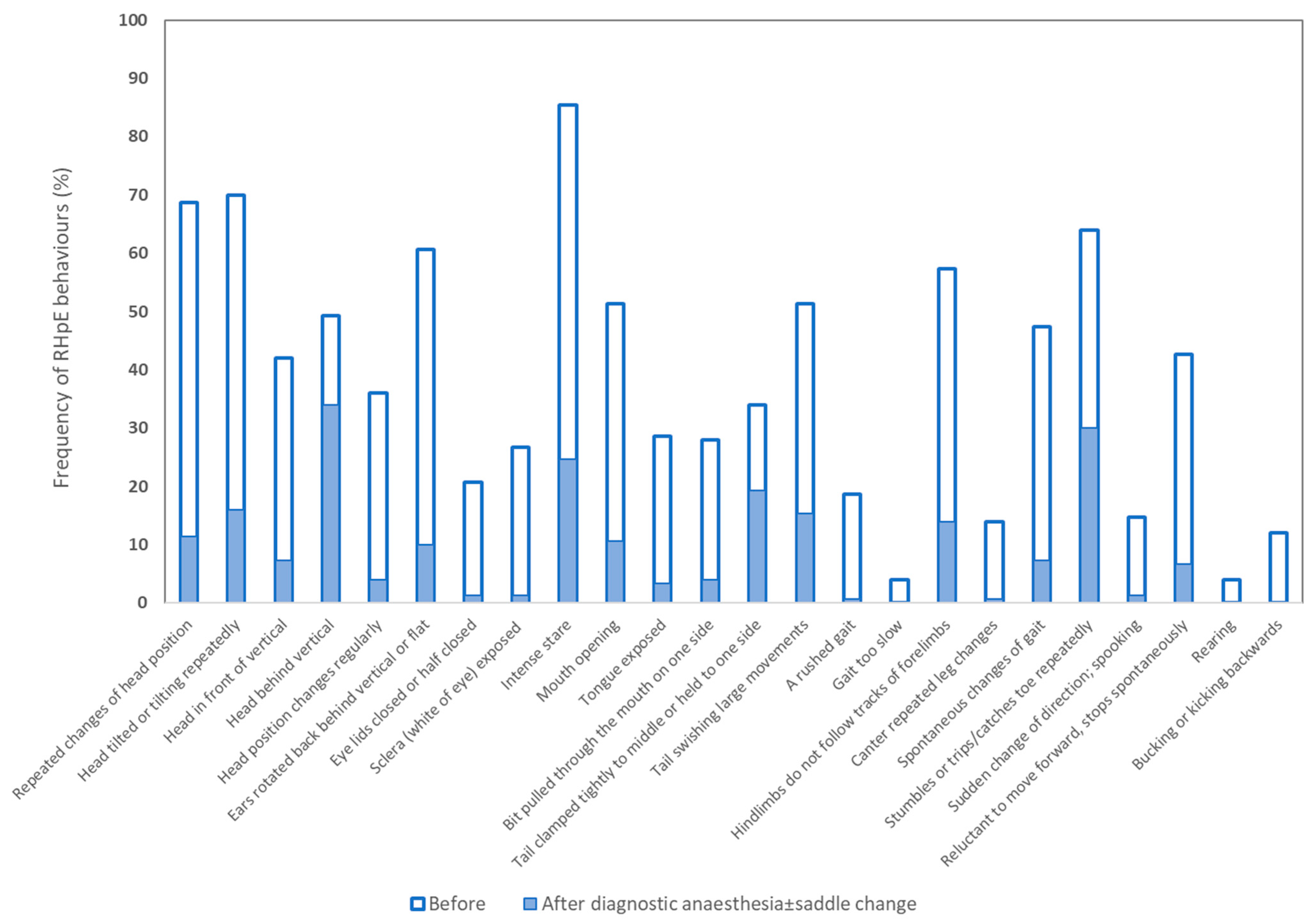

Hoping to fill the need for a tool capable of recognizing musculoskeletal pain in ridden horses, Dyson and colleagues unveiled the ridden horse pain ethogram (RHpE) in 2017. The RHpE is a collection of 24 behaviors, the majority of which are at least 10 times more likely to be seen in a lame horse than a nonlame horse (Dyson, 2022; Dyson and Pollard, 2023; Dyson and Pollard, 2024).

Examples of these behaviors include:

- Repeated change in head position not in rhythm with the trot

- Ears rotated behind vertical or repeatedly lying flat for 5 seconds or more

- Sclera exposed repeatedly

- An intense stare or glazed/zoned-out expression for 5 seconds or more

- The tail clamped tight to middle or held to one side

- A rushed gait or gait too slow

- Hind limbs not following tracks of forelimbs

- Spontaneous changes in gait

- Reluctance to move forward

- Rearing

- Bucking

Dyson explains that the presence of eight or more of these behaviors likely reflects the presence of musculoskeletal pain, although a minority of lame horses have a RHpE score of less than 8 out of 24.

She has validated and applied the RHpE in a variety of settings. In one study she calls particularly valuable, she and Pollard evaluated the RHpE in 150 horses before and after diagnostic anesthesia (nerve and joint blocks using a local anesthetic that helps the veterinarian pinpoint the cause of lameness).

“The rationale for this study is that many riders are frustrated with their horse’s decline in performance, yet a traditional lameness examination in hand or on the longe does not identify any lameness,” says Dyson.

So, 150 horses being evaluated for lameness or poor performance underwent routine examinations, including static and dynamic lameness exams, and crucially including ridden exercise. In addition, Dyson applied the RHpE and performed these tests both before and after any blocking with a local anesthetic.

52 horses exhibited a bilaterally symmetrical short step length and/or restricted hind-limb impulsion and engagement.

53 horses displayed episodic lameness.

45 horses were continuously lame.

Despite a large proportion of horses not appearing conventionally lame, the median RHpE score was 9 out of 24 (with the range being 2-15), which decreased to a median of 2 out of 24 (range 0-12) following blocking.

So, despite the presence of low-grade lameness or only a shortened step length in most horses, the RHpE score clearly demonstrated the presence of pain. The reduction of RHpE scores after nerve blocks clearly showed the behaviors were pain-induced and performance problems were due to pain and not the direct result of a training problem or poor riding.

“Moreover, the riders often unconsciously improved their posture on the horse and commented that the horses were easier to ride and were more responsive to leg and rein cues” after the nerve blocks, says Dyson.

This highlights the importance of riders and trainers recognizing pain-free horses are both more rideable, she says, and enable riders to be in a better position and to experience less discomfort.

“The substantial reduction in RHpE scores after diagnostic anesthesia verifies the value of the RHpE as a tool to determine if most of the pain causing compromises in performance has been resolved,” says Dyson.

Dyson did point out that the spectrum of behaviors does not identify the specific source or sources of the pain. Once a veterinarian suspects musculoskeletal pain, she needs to perform diagnostic analgesia using local nerve and joint blocks to identify the source. Then imaging such as X rays and ultrasound or even advanced imaging including MRI or computed tomography can help her further pinpoint the cause(s) of pain.

Photo: Adobe Stock

Treating Equine Chronic Pain With Joint Injections: What Are Our Options?

Falling under the umbrella of pharmaceutical management of OA, joint injections remain a popular option, particularly for owners of equine athletes that are still competing.

“Intra-articular therapy often provides the most ‘bang for your buck,’ but only when used once an accurate diagnosis of OA has been made while also assessing the affected joint, severity of disease, age and use of the horse, and potential underlying causes or contributing factors,” says Dr. Erin Contino, assistant professor in equine sports medicine at the Colorado State University (CSU) College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Science’s Equine Orthopaedic Research Center.

Products typically used IA include corticosteroids, which, says Contino, remain the “cornerstone for managing joint disease and for a good reason.” These products include betamethasone, methylprednisolone acetate, and perhaps the king of the hill, triamcinolone. Product selection varies depending on your veterinarian’s preference, the amount to be administered, and if it’s a high- or low-motion joint.

Other injectable products include:

- sodium hyaluronate (hyaluronic acid, administered IA or intravenously, depending on the product)

- polysulfated glycosaminoglycan (labeled for IM use)

- pentosan polysulfate sodium (given IM)

- bisphosphonates (only FDA-approved for managing horses diagnosed with navicular disease, available in IM and IV forms)

- polyacrylamide gels (used IA), and IA biological or regenerative therapies such as stem cells, IRAP (interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein), and platelet-rich plasma.

Erin Contino, DVM, Dipl. ACVSMR,

is an assistant professor in equine sports medicine at the Colorado State University (CSU) College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Science’s Equine Orthopaedic Research Center, in Fort Collins. Contino graduated with a veterinary degree from CSU in 2010 and completed a one-year internship at Pioneer Equine Hospital, in California. She then returned to CSU for a three-year sports medicine and rehabilitation residency and became a Diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation in 2014. Before and during her time as a veterinary student, she also completed a master’s degree in equine radiology. Her research interests include equine musculoskeletal imaging, diagnostic analgesia, lameness, and performance issues in equine athletes. In her free time she’s a passionate three-day event rider.

Photo: Getty Images

Treating Chronic Equine Pain With Oral Medications: What Are Our Options?

Back in 2014 researchers published an article about the current knowledge surrounding pain control in horses. “Currently, approaches to pain control in horses lack a robust evidence base,” the authors, Sanchez and Robinson, wrote. “Although research reports of antinociceptive and analgesic (pain-killing) therapy in horses have certainly gained ground over the years, most involve models of healthy horses or retrospective evaluation of clinical cases. Reports of prospective clinical trials are few and far between; thus, most practitioners base analgesic choices upon a combination of the available literature and clinical experience.”

Today the situation remains similar. But here we’ll briefly describe many of the oral pharmaceuticals available for managing chronic pain in horses, addressing the benefits of each while noting some potential drawbacks/adverse effects.

Rachel Hector, DVM, Dipl. ACVAA,

is an assistant professor of veterinary anesthesia and analgesia at CSU. She graduated from Oregon State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine and spent two years in equine practice with Paton and Martin Veterinary Services in Aldergrove, British Columbia, Canada, prior to completing a residency in anesthesia and pain management at CSU and remaining there as faculty. Her clinical focus is in equine practice, with specific expertise in emergency care, pain management, and equine behavior. Her research includes anesthetic management and pharmacologic intervention in the treatment of endotoxemia, positive reinforcement training in a medical setting, behavior-modifying drugs, anesthetic recovery quality, metabolic responses to trauma and acute pain, improving local anesthetic techniques, and chronic pain therapy.

NON-STEROIDAL ANTI-INFLAMMATORY DRUGS (NSAIDS)

These medications are the backbone of most treatment plans for horses with chronic pain, particularly due to OA. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories block enzymes called cyclooxygenase (COX) that produce chemicals called prostaglandins, which are primary mediators of inflammatory pain.

In clinical settings veterinarians most frequently choose Bute as the NSAID for managing chronic musculoskeletal pain.

“Bute is likely the most commonly used NSAID due to the combination of being fairly effective, affordable, readily available, and given orally, as well as only requiring once or twice daily dosing,” McKenzie says. “This has made it popular despite its low therapeutic index, meaning that the difference between a therapeutic dose and a toxic dose is small.”

Veterinarians often choose flunixin meglumine—another common NSAID—to treat visceral pain in colic patients. However, researchers have shown flunixin meglumine is effective for musculoskeletal pain. Alternatively, they might select firocoxib, which is also an NSAID but classified as a highly selective COX-2 inhibitor. This means it blocks only COX-2 enzymes (not COX-1) and therefore causes fewer side effects.

Despite this presumptive improved safety profile, veterinarians rarely prescribe firocoxib compared to Bute. Reasons might include the higher cost, lack of prescriber familiarity with the product, and the perception that COX-2 specific drugs are less effective than the nonselective COX inhibitor phenylbutazone (McKenzie et al., 2023). Head-to-head studies reveal that both selective and nonselective COX inhibitors provide similar pain relief. (Doucet et al., 2008; Orsini et al., 2012).

The main adverse effects associated with NSAIDs include gastric ulcers, right dorsal colitis, and renal (kidney) disease.

“When using NSAIDs the goal should be to provide short- to moderate-term pain relief while identifying other means of lessening the horse’s pain, such as addressing the primary problem with surgery or other interventions,” he adds.

While those are the main pain relievers for horses, additional types available include:

ACETAMINOPHEN

This medication, classified as a nontraditional NSAID, primarily exerts analgesic effects through pathways not involving COX enzymes.

“I am definitely seeing acetaminophen being used more frequently in our region, but that may be because we have worked on communicating its utility to our referring veterinarians,” says McKenzie. “This drug is certainly not the answer to all of our problems, but I do think it has efficacy and true clinical utility, especially when used in combination with other drugs.”

TRAMADOL

This medication inhibits mu opioid receptors (a class involved in neuromodulating different physiological functions), serotonin (a chemical messenger that carries messages between the nerve cells in the brain and the body), and norepinephrine (a neurotransmitter and hormone that helps the body respond to stress).

It also decreases levels of TNF-α (types of cytokines—proteins that act as chemical messengers to regulate immune response—produced during inflammation).

“Tramadol seems to come and go in terms of popularity,” says Dr. Rachel Hector, assistant professor of veterinary anesthesia and analgesia at CSU. “I generally don’t use tramadol as a first-line medication, but I do not dissuade people from trying. My thought is if investing in this treatment doesn’t prevent an owner from spending the money on something else that has more proven efficacy, and the treatment doesn’t produce any negative side effects, then it is worthwhile trying.”

GABAPENTIN

This medication is a human anticonvulsant drug recently found to be effective for chronic or nerve pain in people, cats, and dogs. Veterinarians use gabapentin off-label in horses (meaning it is not approved by the FDA for use in horses for managing pain). Equine researchers have found variable results in terms of how well it works.

“We may never have good studies to prove each and every drug in this species,” Hector says. “If we wait for the perfect study, we may miss helping a horse who is painful now.”

CBD

Perhaps the drug with the greatest enthusiasm behind it of late is CBD (cannabidiol) derived from the hemp plant Cannabis sativa. This interacts with the endocannabinoid system that regulates nociception and inflammation.

In 2024 Interlandi et al. evaluated the efficacy of CBD in 20 horses with mild fetlock OA. They found that horses supplemented with CBD had significantly lower heart rates and respiratory rates, as well as Horse Chronic Pain Scale scores.

“The addition of a cannabidiol-based product to an analgesic protocol was well tolerated and showed positive effects on the treated subjects, improving their quality of life and pain relief,” said the researchers.

AMANTADINE

The neurotransmitter glutamate stimulates N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA, an amino acid derivative) receptors, amplifying pain signals. Amantadine blocks NMDA receptors.

“There are no data on amantadine’s efficacy for pain in horses,” says Hector. “Anecdotally, I think it can be a helpful addition and do prescribe it at 5 mg/kg by mouth once daily, but it is not clear whether this is the right dose or frequency in horses.”

TAPENTADOL

Researchers recently explored this orally administered opioid drug in a preliminary study in horses. Tapentadol acts as a dual mu-receptor agonist like butorphanol and as a norepinephrine/serotonin reuptake inhibitor (NRI/SSRI). It reportedly has double the affinity for mu pain receptors than tramadol.

Costa et al. (2024) reported that tapentadol “may represent a breakthrough in treating chronic pain in veterinary species, serving as an alternative to tramadol.”

Photo: Adobe Stock

Nonpharmacologic Management of OA in Horses: Exercise and Rehabilitation

Dr. Laurie Goodrich, professor of surgery and lameness at CSU’s Johnson Family Equine Hospital, says horses with OA need to keep moving. When horses stop exercising in the face of OA, their joint capsules become fibrotic, and that fibrosis causes more pain, which limits the horse’s ability to exercise.

“It’s a negative feedback loop,” says Goodrich. “We cannot just let the horse sit and rest.”

The type of exercise a horse with OA needs depends on the specific joint and the severity of disease.

“Rehabilitation may include flexion and extension exercises, but truly there is no blanket protocol for these horses,” says Goodrich. “Owners need to work with their veterinarian and a certified rehabilitation specialist.”

She says she believes an underwater treadmill is great for arthritic horses.

“With the water there are a lot less direct mechanical forces on the joints, and ligaments and tendons can get exercised without those forces,” Goodrich explains. “Many rehabilitation programs with treadmills aren’t cheap but worth it, allowing horses to continue exercising.”

When choosing a rehabilitation specialist, Goodrich advises looking for centers operated by a diplomate of the American Association of Veterinary Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation. These types of facilities operate around the country and should be considered before using uncertified individuals.

And not to be overlooked is the effect of obesity on joint health. According to Pratt-Phillips and Munjizun (2023), “Excess body weight has been documented to affect gait quality, cause heat stress and is expected to hasten the incidence of arthritis development.”

Laurie Goodrich, DVM, MS, PhD, Dipl. ACVS,

is a professor of orthopedics in the Department of Clinical Sciences at CSU. She received her DVM from the University of Illinois in 1991 and PhD in cellular and molecular biology in 2004. In her laboratory she and her colleagues study new approaches to bone and joint healing in equine athletes and employ both gene therapy and stem cell therapy. Ongoing studies include using adeno-associated viral vectors to deliver growth factors and anti-inflammatory molecules important in cartilage and bone healing. Goodrich has used mesenchymal stem cells and platelet-rich plasma to improve cartilage repair. Further studies utilizing gene therapy combined with stem cell therapies to improve musculoskeletal repair are currently underway.

Photo: Adobe Stock

Oral Joint Health Supplements for Horses

According to results of a recent survey of U.S. horse owners (Herbst et al., 2023), OA was the most common medical condition affecting senior horses. A total of 41.4% of the 2,374 survey respondents used nutritional supplements for OA, making them the most popular supplement class offered to horses and supporting the findings of other studies (Murray et al., 2018).

One of the main concerns veterinarians express regarding joint supplements is the lack of regulatory oversight and, therefore, the number of poor-quality supplements (Oke et al., 2006). Using products that do not contain the type or amount of ingredients listed might not be effective and could delay the use of potentially effective therapies.

In terms of efficacy, published studies contain conflicting results; however, researchers on multiple studies have shown that joint supplements containing ingredients such as glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and avocado-soybean unsaponifiables (ASU), benefit joint health. Notably, joint supplements offered to healthy horses prior to the onset of trauma and inflammation have a protective effect in joints (van de Water et al., 2016).

Take-Home Message

No one single drug is ever going to be the silver bullet, especially in chronic pain cases,” Hector says. “One drug may give you only 10% of an effect, for example, but combined with two other drugs that give you 10% effect you end up with a 30% reduction in pain, which is a significant improvement.”

Dyson reminds us not to forget the nonpharmacologic aspect of pain management. “I think it’s hugely important to consider the holistic approach to the horse,” she says. “This includes controlling obesity; good-quality farriery performed with adequate frequency; saddle fit for horse and rider; turnout for movement; exercise programs; cross training (i.e., getting out of arenas); rider fitness and balance; groundwork exercise to promote core strength and stability; and managing competition schedules.”

Horse owners need to become better educated on how to identify the more subtle signs of a horse in pain. Then, a committed team of owner and veterinarians with a structured plan and dedication to sticking to it can help a horse in pain live a more comfortable life.

Sponsor Message

Horses are powerful, athletic animals, but they are also remarkably sensitive. Pain, whether from injury, arthritis, or chronic conditions, can significantly impact their performance, mood, and overall well-being. Unfortunately, horses are masters at masking discomfort, making it challenging for owners to detect and address pain early.

Common signs of pain in horses include stiffness, reluctance to move, changes in behavior, and a decline in performance. Subtle shifts, such as an unwillingness to be saddled or an uncharacteristic change in gait, can indicate underlying discomfort. If left untreated, pain can lead to long-term mobility issues, reduced quality of life, and even behavioral problems.

Fortunately, advances in equine care have provided effective solutions for managing pain. Veterinarians can recommend a variety of treatments, including anti-inflammatory medications, joint supplements, physical therapy, and proper hoof care. In some cases, alternative therapies like acupuncture and massage can also provide relief.

By recognizing the signs of pain early and seeking the right treatment, horse owners can ensure their equine partners remain healthy, happy, and sound. Regular check-ups, a balanced diet, and appropriate exercise all play a crucial role in keeping horses comfortable and active.

Don’t let pain hold your horse back—work with your veterinarian to find the best solutions for long-term health and mobility.

Credits

Stacey Oke

Stacey Oke, MS, DVM, is a practicing veterinarian and freelance medical writer and editor. She is interested in both large and small animals, as well as complementary and alternative medicine. Since 2005 she’s worked as a research consultant for nutritional supplement companies, assisted physicians and veterinarians in publishing research articles and textbooks, and written for a number of educational magazines and websites.

Stacey Oke, MS, DVM, is a practicing veterinarian and freelance medical writer and editor. She is interested in both large and small animals, as well as complementary and alternative medicine. Since 2005 she’s worked as a research consultant for nutritional supplement companies, assisted physicians and veterinarians in publishing research articles and textbooks, and written for a number of educational magazines and websites.

Editorial Director: Stephanie L. Church

Managing Editor: Stephanie J. Ruff

Digital Editor: Haylie Kerstetter

Art Director: Claudia Summers

Web Producer: Jennifer Whittle