Equine First-Aid Basics, Part 2

It’s time to hone your equine emergency skills

No one wants to deal with an equine emergency. But being prepared—with both tools and skills—can help make the situation less stressful and result in a more positive outcome.

In part one of this series, we looked at the items you should keep in an easily accessible first-aid kit. Now our sources will describe how to use them and how you can improve your skills for managing an equine emergency until the veterinarian arrives.

The Best Instructor: Your Veterinarian

Nothing beats hands-on training for learning some of the useful skills we’ll address in this article.

Equine emergency management instructional clinics are rare, so your best bet for skills training is going to be with your veterinarian, says Matthew Randolph, DVM, of the Equine Veterinary Hospital of Northern Indiana, in Bremen. If you have a good relationship with your veterinarian, he or she will probably be more than happy to show you these basic skills that will help you both during emergency situations.

“Your horse’s spring or fall vaccination appointment is a great time to get some skill sets from your veterinarian,” says Randolph, who adds that he appreciates having knowledgeable clients that are adept with handling an emergency until he can get there. “Have your kit handy, and ask your vet to show you how to use that stethoscope or those wraps and how to give medications.”

In the meantime, though, help yourself to veterinarian-produced how-to videos, says Meg Hammond, DVM, of Woodside Equine Clinic, in Ashland, Virginia. Woodside, for instance, offers online skills-training demonstrations on its website. “It’s not hands-on, but at least it’s a visual that’s in motion rather than just still pictures,” she says.

You can find how-to and informational videos at TheHorse.com/videos.

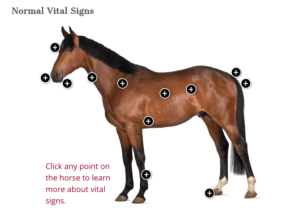

Vital Signs: Knowing What’s Normal

When taking a horse’s vital signs—temperature, heart rate, and respiratory rate—it’s important to have a basis for comparison. None of your readings will mean anything if you don’t know what’s normal for your horse.

For adult horses, normal temperature is 99-101°F (37.2-38.3°C); normal heart rate is 28-44 beats per minute (just about half of what the average human heart rate is); and normal respiratory rate is 10-24 breaths per minute (similar to humans’ respiratory rate). And, no, you can’t guess on these, and—except in the case of the respiratory rate—you can’t tell by just looking.

“It’s amazing how many people answer the fever question by saying, ‘Well, he’s not sweating,’ or ‘he doesn’t look like he has a fever,’ ” says Benjamin Buchanan, DVM, Dipl. ACVIM, ACVECC, of Brazos Valley Equine Hospital, in Navasota, Texas. “The only way to really know that answer is to take his temperature.”

To take a temperature reading accurately, be sure the digital thermometer remains inserted in the rectum for the required duration, which varies based on the thermometer; wait for the beep before you remove it. If you only have access to a glass thermometer, tie a string to it and use a clothespin to attach it to the horse’s tail, leaving it inserted for three to five minutes. Be sure to shake it down before use.

Take your horse’s heart rate by feeling for the cordlike mandibular artery on the inside of your horse’s jawbone. Count the number of beats you feel in 15 seconds, multiplying that by four to determine resting heart rate. You can also use a stethoscope to listen to the heart rate on the horse’s left side, on the ribs just behind the elbow.

“Don’t confuse the ‘lub-dub-lub-dub,’ like in humans, with the ‘lub … dub … lub … dub’ in horses,” warns Randolph. “Owners frequently make the mistake of giving me a heart rate that’s double what it really is because they’re counting both parts of the beat.”

Respiratory rates, though, are relatively easy to calculate: Just count the number of breaths your horse takes in one minute while watching his flank or nostril or by using a stethoscope.

You should also be familiar with normal gut sounds, in the case of a colicky horse. “What we like to hear is something that’s moving,” says Randolph. “It should gurgle and squeeze in one place and then gurgle and squeeze a little farther down the line a little bit later.” You don’t want to hear “washing machine sounds,” he adds. And you definitely don’t want to hear silence.

Using a stethoscope, practice listening to normal gut sounds on both sides, high and low, of the abdomen when your horse is healthy, he says. In an emergency, you might compare your sick horse’s gut sounds to those of a nearby healthy horse—keeping in mind that each horse is different.

And in general, know what’s normal for your horse—his appetite, his usual water intake, his urine and manure output, but also his behavior and activities, says Hammond. Did he not finish his grain this morning? Is he lying down more than normal?

“A lot of emergencies can be caught early, just by recognizing signs that your horse isn’t his usual self,” she says.

Wound Care: Taking it Easy

Got an open wound? Go easy on it. Our sources caution that you can quickly overdo wound care by cleaning too much, wrapping too tightly, and not using enough padding. Equine wounds—particularly on the legs—require special wound care skills.

For one thing, overcleaning can be disastrous, says Randolph. “Don’t get so aggressive with scrubbing that you slow down blood clotting and make things worse,” he says. Just some mild hand soap will suffice until the veterinarian arrives.

For bandaging, learn how to pad and wrap so you’ll be ready for when an injury happens. “It’s very important to have a good handle on the amount of padding and the amount of pressure (not too much, and not too little) that you need in wrapping a wound,” Hammond says. “It’s really easy to cause further injury with an improperly applied bandage.”

Oral Meds: Over and Under the Tongue

Your veterinarian might prescribe medications to help treat a condition or relieve pain. By far the easiest and most practical method of giving a horse medications is orally. “If you can administer a basic dewormer, you can administer an oral medication,” says Hammond.

Banamine oral paste can often relieve pain, including colic pain, she says. It goes over the back of the tongue like a dewormer so the horse can swallow it. Others, however, are “sublingual” medications—meaning they go under the tongue to be absorbed instead of swallowed. Know what type of drug your veterinarian has prescribed so you can administer it properly.

Follow your veterinarian’s recommended oral dose, and make sure the horse doesn’t spit it out or drop it. Holding the horse’s head up until he swallows can be helpful, Hammond adds.

Injections: Best Handled By the Veterinarian

Injections offer the added advantage of working faster than oral medications in some cases, but they require veterinary skill.

Depending on the prescribed medication, injections are given via three routes: intravenous (IV, into the jugular vein in the neck), intramuscular (IM, into the neck or rump), and subcutaneous (sub-q, under the skin and above the muscle).

While some people around the barn might perform their own injections, recognize that the risks with this procedure are significant.

An incorrectly placed injection can be very dangerous. For example, a Banamine injection into a muscle instead of a vein could cause severe, painful, and long-lasting side effects, Buchanan says. And unskilled jugular punctures could cause the jugular vein to “collapse,” meaning it can no longer withstand injections. Worse, if you accidentally hit the carotid artery—which lies just beneath the jugular vein—you could send your horse into a severe seizure or, worse, cause sudden death, Hammond says.

So, our sources agree that it’s best to leave injections in the capable hands of your veterinarian.

Eye Care: Tricky Business

When your horse’s eye hurts, of course you don’t want to make it worse. Yet eye ointment application can be tricky, especially in an animal that can’t understand that you’re trying to help, not hurt. And if you get into a struggle, it’s possible to cause more damage to the eye.

Do not use any eye ointment without specific advice from your veterinarian. Be sure to use a fresh tube of ointment that he or she recommends that would be safe for any condition. And don’t reuse the same ointment on a subsequent horse.

If you can’t get the eye open easily to apply the medication, just wait for the veterinarian.

“If an eye is really painful and held tightly closed, you don’t want to pry it open,” Hammond says. “In the case of a severe ulcer, the cornea can become very thin and fragile. That pressure can cause further damage if the eye is already compromised.”

If you do apply ointment, keep a hand on the horse’s head to better follow his movements. “I always recommend keeping the heel of your ‘medication’ hand on the horse’s face when delivering eye ointments,” Hammond says. Point the tube parallel to the horse’s eye, not toward it, so you don’t risk jabbing it.

“You can alternatively place some of the ointment onto a gloved finger and apply it with that,” she adds. “This decreases the risk that you may cause trauma with the ointment tube.”

Horses are typically less resistant to having ointment applied to the bottom eyelid, says Hammond, and “the medication will disperse across the eye as soon as the horse blinks.”

Finding Reliable Resources

When something’s wrong with your horse, it’s easy to just Google his clinical signs and look for answers. But beware: Our sources say there’s an abundance of unreliable information on the internet.

That doesn’t mean you should avoid seeking out information completely, they say. In fact, veterinarians generally appreciate working with well-informed owners. The trick is knowing how to choose your sources.

“I love educated clients,” says Matthew Randolph, DVM, of the Equine Veterinary Hospital of Northern Indiana, in Bremen. “It’s much easier to talk with someone who’s educated themselves on horse health. But there are a lot of websites out there, and just because it’s online doesn’t mean it’s the gospel.” TheHorse.com is a great resource, he adds. “Those clients (who read The Horse) usually have a good idea of what they’re talking about.”

—Christa Lesté-Lasserre, MA

Calling the Vet

Relaying information to your veterinarian is also a learned skill. Owners should know what to assess in an unwell horse and how to describe what they see, which is a matter of practice and dialogue with the veterinarian.

“Don’t be vague,” Randolph says. “I can’t work with ‘he’s not himself.’ Tell me what’s unusual, and be specific. He can’t put his leg on the ground. Or he can put the leg down but won’t put weight on it. And when was the last time you saw him normal? What have you already tried?” He says he even encourages clients to send him photos or videos in an emergency.

Don’t bother scoring facial grimaces or pain behaviors, because even health care professionals require extensive training on these scales to make accurate assessments. Better to simply judge the perceived pain on a scale of 1 to 10, our sources say. And detail the horse’s actions. “Describe what you’re seeing; that helps more than a scale,” says Hammond.

Knowing When to Get Help

A common mistake among horse owners dealing with emergencies is simply not making the decision to consult their vet. And it’s too bad, because making this call is probably the easiest of all. When the horse isn’t well, call the veterinarian. Period.

“When in doubt, call,” says Hammond. “Early care saves time and money and reduces your horse’s discomfort sooner.”

Calling your veterinarian doesn’t necessarily mean an expensive emergency farm call bill will show up in your mailbox a week later. Rather, this is a good way to get a dialogue started about what’s going on with your horse. It lets the veterinarian know that he or she needs to be ready to come out to the farm, depending on how your horse progresses.

Take-Home Message

Being prepared for your horse’s emergency or health scare requires not only a good medical kit but also a strong skill set. If you take a moment to learn equine first-aid skills from your veterinarian and get used to recognizing what’s normal in your horses, you’ll have a great head start on managing your horse’s health problem. And if you learn useful observation and communication skills, you’ll be well on the road to active, productive teamwork with your horse’s health care professionals to ensure he’s getting the most effective and prompt treatment possible.

Written by:

Christa Lesté-Lasserre, MA

Related Articles

Stay on top of the most recent Horse Health news with