Case Study: 2020 Equine Coronavirus Outbreak in Japan

Only a third of the horses showed signs of equine coronavirus (ECoV) disease—mainly fever, lethargy, and loss of appetite, with a few cases of diarrhea. However, the other two-thirds tested positive for the coronavirus and likely contributed to its spread across the facility, with some horses shedding the virus for more than 50 days, said Manabu Nemoto, DVM, PhD, of the Equine Research Institute at the Japan Racing Association, in Tochigi.

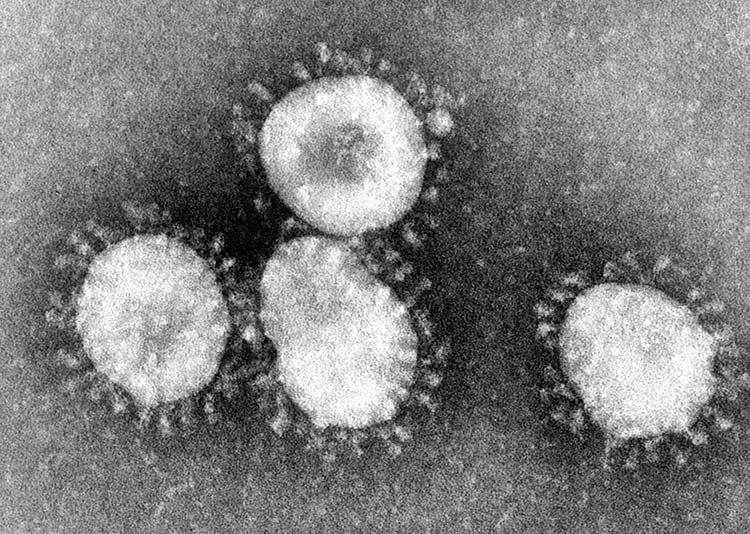

The statistics aren’t surprising for ECoV—which is not to be confused with the COVID-19 coronavirus, said Nemoto. However, they do underline the importance of enacting strict biosecurity when outbreaks occur, as well as recognizing the disease, .

“Usually, ECoV is not a highly pathogenic (disease-causing) virus, but it is a highly contagious one,” he said. “And it’s not a well-known viral disease. So when several horses show a fever, lack of appetite, lethargy, and sometimes diarrhea, I hope horse owners and farm managers add ECoV infection to their checklist.”

Handlers at the Tokyo Racecourse noticed the first cases in mid-March 2020—when Japan was already dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. Three of the stable’s 41 horses, which had just returned from a competition 31 miles away, developed mild fevers. Over the next several weeks, more horses developed fevers, sometimes with lethargy and loss of appetite, and three horses also had diarrhea.

Fifteen horses total became sick. Early in the epidemic, veterinarians suspected a viral disease and tested for equine herpesvirus types 1 and 4 (EHV-1 and EHV-4), equine influenza virus, Getah virus, and equine arteritis virus, but all were negative. It wasn’t until they saw the first case of diarrhea (in the eleventh sick horse) that they decided to perform a real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for ECoV and got a positive result. Virus neutralization testing revealed all 41 horses in the stable were positive for ECoV.

Meanwhile, researchers tested the horses’ feces via RT-PCR every week to see how long they shed the virus—meaning how long they were contagious. They found that shedding times ranged dramatically, from one day to 98 days, Nemoto said.

Interestingly, he added, they found that Thoroughbreds didn’t shed nearly as long as the other breeds. The stable included 16 Thoroughbreds and 25 non-Thoroughbreds, including Andalusians, ponies, Miniature Horses, Friesians, Lusitanos, and Japanese breeds. The Thoroughbreds mainly shed for about a day (although one shed for 19 days). Median shedding time for the other horses was eight days, and four of them went much longer: 98, 88, and 50 days in two horses.

“The difference in shedding periods among horse breeds may indicate that some breeds excrete ECoV longer than other breeds and can contribute to the spread of ECoV,” the researchers stated in their study published in Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases.

While the outbreak occurred during the COVID-19 outbreak in Japan, the research team does not suspect a link. “ECoV is clearly different from SARS-CoV2 (which causes COVID-19),” Nemoto said, adding that they did not test the horses for COVID-19.

Even so, the human pandemic did interfere with their management of the ECoV outbreak. “Our lab struggled to deal with the outbreak because we did not work freely due to lockdown,” he said.

Written by:

Christa Lesté-Lasserre, MA

Related Articles

Stay on top of the most recent Horse Health news with