Navigating Natural Disasters with Horses

Careful preparation and rapid response are crucial for minimizing injury and loss during disasters such as wildfires

No one wants to envision what might happen to their horses if suddenly faced with a flood, hurricane, tornado, wildfire, earthquake, or other disaster, but in certain parts of the country these devastating events can be a part of life, and horse owners must be ready for them. Of course, location makes a difference in what to prepare for: Horse owners in the Rocky Mountains don’t need to worry about hurricanes or tornadoes, for instance, but they might be threatened by raging wildfires.

Regardless of where you and your horse live, you need to establish and record a plan for these types of situations. “There may not be much time to figure things out during an emergency, so you need an exit strategy—how to get out, safely, with your animals and secure your place before you leave,” says Rustin Moore, DVM, PhD, Dipl. ACVS, professor and associate dean for clinical and outreach programs at The Ohio State University’s Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences.

Moore helped coordinate Gulf Coast hurricane relief for horses and owners in 2005 and 2006, seeing the gamut of what can happen to horse owners—prepared and not. He suggests at the very least having first-aid supplies on hand and easy-to-access contact information for veterinarians and people who could help transport your horses in the event of an evacuation—especially if you don’t have a trailer or if you have more horses than you can haul with your rig. He and other veterinarians experienced with disaster response offer ways to be ready if disaster hits.

Watch Closely and Don’t Wait

If you live in a natural disaster-prone area, pay attention to weather forecasts and situation reports. While tornadoes can pop up rapidly, hurricanes, floods, or wildfires usually come with some notice. If there’s an out-of-control fire in your area, however, and the forecast is for high winds, act quickly; a fire can travel dozens of miles in a few minutes.

“Don’t wait until the last minute, thinking the fire won’t get to your place, or that a hurricane will miss you or be less powerful than predicted,” says Moore. “With Hurricane Katrina, people had plenty of time to get out, but ignored the warnings until it was too late. Part of the issue was unpredictable things that happened, like the levees breaking, causing flooding.”

Dennis French, DVM, professor at the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine, was also involved in recovering horses impacted by Katrina. He says it’s important to have trailers functional, serviced, and ready to go at a moment’s notice–whether to relocate your own horses or to rescue others. You can’t just grab an old trailer that’s been sitting unused and expect it to be functional.

Also be able to leave your farm quickly: this means having horses trained to load. If you don’t own a trailer, borrow one so you can teach your horse(s) to load. Like a fire drill for school children, horses need to know what to expect so you won’t waste time trying to load a reluctant horse.

John Madigan, DVM, MS, a professor in the Department of Medicine and Epidemiology at the University of California, Davis (UC Davis), School of Veterinary Medicine, says if there’s a flood, fire, or hurricane warning, evacuating early is crucial, even if you aren’t immediately sure where you will go. If you are in an at-risk area, load up the horses and leave the farm, then use communication resources such as radio, texting, or social networking to find out where you can go with your animals.

“Some people try to get all the information about where they could go, but the first thing to do is get out of harm’s way,” he says.

What if You’re Stranded?

In some situations you might not be able to leave home right away. “Maybe the roads are closed, or a train is derailed and blocking the only exit,” says Rebecca McConnico, DVM, PhD, Dipl. ACVIM, associate professor of veterinary medicine at Louisiana State University. “There might be food drops for people, but animals may not have attention until human needs are met. Do you have enough feed and clean water for X amount of days for your horses?”

She suggests keeping plastic 50-gallon barrels on hand to fill with uncontaminated water for your horses (or your family). Also store some hay up off the ground if there’s a chance of flooding.

“Some people think they need to stockpile grain, but horses don’t need grain if they have hay,” says McConnico. “If there’s no hay available, they could live on a commercial ‘complete diet’ product.”

John Madigan, DVM, MS, professor in the Department of Medicine and Epidemiology at the University of California, Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine, says a small generator could be very important if you have no power and can’t pump well water. Many people are affected secondarily (even if their area was not flooded, burned, or buried in heavy snowfall) because they don’t have power. For instance, “Here in California earthquakes usually cause structural loss, and the secondary problem is loss of power and water,” says Madigan.

—Heather Smith Thomas

Evacuating with Horses

If immediate evacuation is necessary and you only have a few hours to get out, would you be able to exit efficiently? Rebecca McConnico, DVM, PhD, Dipl. ACVIM, associate professor of veterinary medicine at Louisiana State University, notes the importance of fuel reserves, being able to hitch the trailer, and having horses that load well.

Have plenty of halters and lead ropes on hand; store buckets and a hose where they’re handy for packing; make sure all horses have up-to-date health papers; and know where these and other equipment and information you might need are located at a moment’s notice. Always have at least a half tank of gas in your truck. If you head out with horses, pack the hay and equipment and anything you and your horses need to subsist if you land at a facility without these basics available. If you go to an empty fairgrounds, for instance, and there are no hoses or buckets, you’ll need these items to water your horse.

Also know ahead of time where you’re heading. For example, if you live in a region likely to flood, be aware of facilities on high ground. Knowing about these and other horse-friendly places (e.g., fairgrounds, racetracks) in case of emergency evacuation is important.

McConnico says it’s crucial to keep vaccinations up-to-date and Coggins documentation current. “Maybe you are a month overdue with this, and then suddenly have to evacuate your horses and take them to a place that won’t let them onto the property unless you can show they’ve been vaccinated or have a current negative Coggins test,” she says.

Another reason to keep up with vaccinations is that your horses could be exposed to other animals in this scenario. There’s also risk for injury if your horse has to fend for himself, so tetanus vaccines should be ¬current.

All told, every plan will be different, depending on your location and situation. “There could be two adjacent farms with very different situations,” says Moore. “One has a trailer and one doesn’t. One has a dozen horses, the other has one. Evacuation plans must be customized.”

If You Have to Leave Your Horses

If you need to evacuate and have to leave your horses behind, make sure they’ll have water for several days. “Feed is not as important as water,” says Moore. “It helps if they have access to hay or pasture versus locked in a stall, but drinking is the most important.”

French says that even five to 10 gallons of water will help a horse survive longer than if he had none. People also wonder whether it’s better to leave horses indoors or turn them out. “One thing we learned, dealing with hurricanes in Louisiana, regarding whether to leave horses indoors or turn them out in the face of a storm, is that turning them out is probably better. There’s always risk that a tree might fall on them, but they wouldn’t be trapped in the barn. This also applies in a flood,” he says.

Horses also can find high ground if they are not confined. If a wildfire sweeps through your farm, for instance, they might be safer in an open pasture than trapped in a barn or paddock. In most situations (but not all—if you’re horses are located near a major highway, for instance, where their chances of being struck by a vehicle are higher than being injured in the impending disaster), horses are better off outdoors. Some owners might be reluctant to turn them loose, but it could save the animals’ lives.

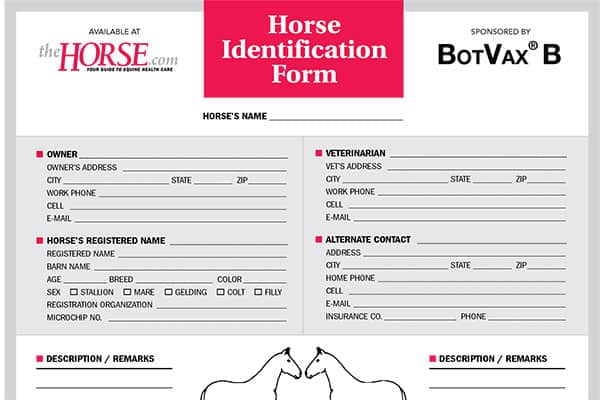

Horse Identification

If you have to leave your animals behind, it’s helpful if they have permanent identification such as a tattoo, registered microchip, brand, or an iris scan on file. “If they don’t, many people use spray paint or livestock markers (such as the “Paintstiks” used to identify animals at an auction) to put temporary ID information on the animals before turning them loose,” says French. Other methods of identification and providing contact information include a band/tag around the horse’s pastern; a phone number body-clipped into the horse’s hair coat; a luggage tag braided into the mane; or a halter with a tag (although the latter two might end up caught on something and/or pulled off).

“It’s great to put a phone number on the horse’s side, but use the number of a friend or relative outside your area,” says French. “When we were working with rescued horses from Katrina, we couldn’t reach owners with home phone or cell phone because there was no phone service (as is the case in many large-scale disasters). Use the number of someone who can be reached,” says French.

He explains that after hurricanes Katrina and Rita, some people stole loose or unattended horses. “A disaster brings out the best in people and the worst in people. There are some who take advantage of the situation,” says French. But if your horse has identification there’s less risk of falling through the cracks. “If someone comes to claim a horse, we want to make sure they have proof of ownership.”

Madigan says it helps to have a photo of the animal, in case you have to drop him off at an evacuation facility or other location and then prove he’s your horse when you return. If there are 2,000 horses at a fairground, for example, it’s good to have a photograph of you with your own horse, even if it’s a digital image.

Wildfire Awareness

Horse owners living in arid regions must be prepared for fires, especially if property is adjacent to forested or ungrazed pastures or public land. It’s crucial to practice diligent preventive measures on your own property and have an evacuation plan (such as that described for other disasters) if wildfire cannot be halted before it reaches you.

Dry vegetation is your greatest fire danger. Mow weedy pastures before the weeds dry out, and remove all debris, dead/dry plants, and dense tree stands within at least a 30-foot radius around any buildings. During a severe drought watering your pastures might be impossible, but try to keep things green around your house and barn area or mowed/grazed so there is not enough dry fuel to carry a fire.

Buildings in arid climates should not be close together; open space between them might prevent fire from jumping from one to another. Construction materials such as metal roofs and fencing might also help prevent fire spread. Roadways should be at least 10 to 18 feet wide to provide adequate access and turnaround areas for fire-fighting equipment.

Have adequate water sources—preferably an irrigation mainline or a pond/stream firefighters can pump from—for fighting fire. The fire department probably can’t save your barn and buildings if all you have are hydrants for watering horses. If fire is approaching but not yet dangerous enough for evacuation, keep your yard and buildings watered down to prevent drifting embers from igniting them.

In case of evacuation, have extra halters and ropes on hand, and ensure they are not nylon, which will melt in high heat and cause injury. Bring with you wire cutters, crowbar, first aid kit, buckets, flashlight and batteries, gloves, boots, and towels (for possible use as blindfolds), and wet down the horses’ manes and tails. If you have to leave quickly without your horses, turn them out into a big pasture; don’t leave any animals in barns or small pens with no escape route.

—Heather Smith Thomas

Resources and Communication

Madigan says it’s important to find reliable information resources in the event of a disaster. There might be a horse evacuation group or community organization that has a Facebook page detailing what facilities and roads are open. Communication via other social networks (i.e., Twitter) can be useful as well. If mobile phone services are down, you might still have texting capabilities, so it helps to have a texting-capable phone and be able to charge it when the battery goes flat.

“In Hurricane Katrina we didn’t have any way to communicate,” says McConnico. “Texting worked a little in our situation, but you can’t always count on it. If the electricity is out and you don’t have a battery, then what do you do? You might use OnStar satellite communication to collect information needed and to get word out that there’s a horse or 50 horses that need assistance, or that there’s someone available who could provide assistance.”

McConnico also suggests identifying your resources for the particular situations that might affect you. “A lot of information will come from communicating with people in your area to find out what your resources are as a family, as a barn, or local group,” she explains. For instance, residents of Southern California and other arid regions usually have a wildfire plan because they’ve been through it before.

“We encourage people to have a partner to work with in case of disaster,” McConnico adds. “A stable owner should have a partner barn; a veterinary practice should have a partner practice in the same town and another one in a different region–in case of a widespread disaster. We try to keep the organized resources within one state, if possible, so we don’t have to worry about interstate agreements or memorandums of understanding, or horse travel between states.”

Organizations such as the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) and universities such as UC Davis offer publications designed to educate horse owners about disaster preparedness. These and other organizations also offer materials for training first responders in emergency and disaster situations, so they are better prepared for horse and other livestock evacuations, emergency animal sheltering, loose livestock management, etc.

Madigan helped write the AAEP’s emergency guidelines and says, “With a little planning and preparation, many things go more smoothly.”

Take-Home Message: Plan for Preparedness

Coordinating area disaster response plans can and should involve the entire equine community. “If you want your town or equine group to prepare for emergencies, plan some meetings with a potluck get-together,” says McConnico. “Get kids and parents involved, utilizing leaders and experts who have been through disaster situations. Put a plan together, building on what you have in place already. Find out who your leaders are and the people you could count on. Make a list of people who have horse trailers. Work what you have and keep improving readiness.”

Some people with experience helping in disaster situations travel around the country on speaking tours, working with groups to help them prepare for emergencies. Someone in your town or region might be interested doing this—you just need to find them.

Also find out where the closest large animal technical rescue group is located. Even in an isolated incident—like a horse falling into a swimming pool or through ice on a pond, or becoming trapped in a trailer—you might need emergency help.

Regardless of where you and your horses call home, be prepared for emergencies well ahead of time and have a plan for when disaster strikes.

Written by:

Heather Smith Thomas

Related Articles

Stay on top of the most recent Horse Health news with