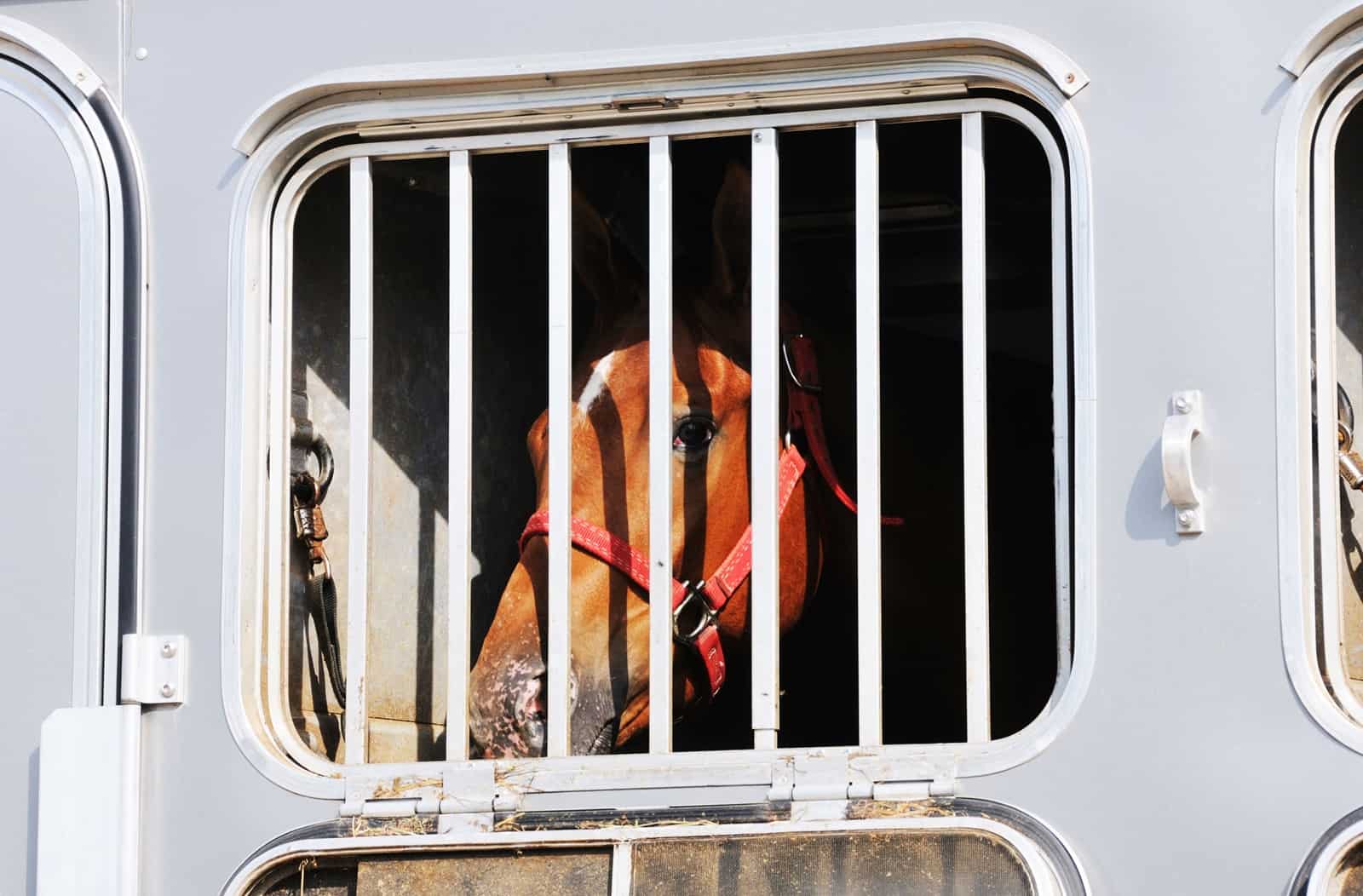

The 411 on Equine Shipping Fever

Researchers have shown that these horses’ stress responses are partly to blame, causing adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), glucose, and white blood cell levels to rise. Higher ACTH levels lead to increased secretion of cortisol, known as the stress hormone. The longer the horse’s transit time, the greater the stress response, potentially resulting in pneumonia and pleuropneumonia.

Other factors associated with shipping fever include the horse’s inability to lower his head during shipment, ambient conditions and air quality, diseases such as strangles, viral disease, and pre-existing airway disease.

Clinical signs of fever and increased respiratory rate usually appear within 24 to 72 hours after shipment. Horses can also exhibit depression, loss of appetite, fever, nasal discharge, and coughing.

Veterinarians can often resolve this by administering non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs). But it’s important to call your veterinarian immediately upon seeing signs, because shipping fever can progress to pleuropneumonia, which can escalate quickly and result in serious complications if not addressed quickly.

If clinical signs worsen despite initial veterinary treatment, diagnostic tools are key. Your veterinarian might first run bloodwork. Having a baseline white blood cell count can help him or her evaluate disease progression. Packed cell volume (PCV, the percentage of red blood cells compared to plasma) and total protein indicate hydration status and can dictate whether the horse needs intravenous (IV) fluids. Also useful is a chemistry test, or at least kidney enzyme measurements, because often these horses are dehydrated. Dehydration makes the kidneys susceptible to damage from NSAID usage; therefore, it’s important to know kidney status prior to administering NSAIDs.

Recently, serum amyloid A (SAA) has become a popular biomarker of inflammation and infection. This is an acute phase protein that rises quickly during an infection and whose trends can help veterinarians monitor treatment response.

Using ultrasound, a veterinarian can identify pleural roughening (“comet tails” in the space between the body wall and the lung) in mild cases, ranging from lung consolidation (the tissue fills with liquid) to abscesses and pleural effusion (excessive fluid accumulation) in more severe cases. Documenting the extent of pleural involvement and the size of consolidation and abscesses is important for evaluating how the horse responds to treatment.

Finally, in severe cases the veterinarian might perform a transtracheal wash to obtain a sterile sample for bacteriology. This can help him or her hone in on the bacteria involved and gauge their sensitivity to medications. In cases with significant pleural effusion, he or she might culture the fluid and test its sensitivity.

Initially, your horse’s treatment plan might include the following therapies:

- NSAIDs to maintain a consistently normal temperature.

- Antibiotics Your veterinarian might administer metronidazole and broad-spectrum antibiotics based on what has worked in the past for similar cases until he or she receives culture and sensitivity results from the lab.

- IV fluid therapy Horses that aren’t drinking or are dehydrated need IV fluids. Rechecking PCV daily can help your veterinarian determine how long to continue fluids.

Other treatment options, if the condition continues to progress, might include:

- Clenbuterol This bronchodilator opens the airways, allowing mucous clearance and better penetration of antibiotics.

- Nebulization In my and my colleagues’ experience, horses tolerate nebulization (inhaling aerosolized medications into the lungs) of antibiotics well and respond well when it’s used as an adjunct treatment.

In severe cases of pleural effusion, veterinarians might pursue a chest tube or a rib resection.

As with everything veterinarians treat, prevention is key. To avoid shipping fever, offer your horse plenty of water and low-dust hay during the journey and ensure he has adequate ventilation. Allowing the horse to lower his head periodically during shipment has been shown to decrease shipping fever risk. If possible, ship your horse in a box stall. Some owners might choose to have their veterinarians administer IV fluids prior to trailering to prevent dehydration stress, especially in horses that do not drink when trailered.

Written by:

Samantha Miles, BVM&S, MRCVS

Related Articles

Stay on top of the most recent Horse Health news with