A Breed Apart: Cooled and Frozen Semen

The shipping of cooled and frozen semen has opened the door to a wide variety of breeding opportunities for horse owners, providing, of course, that their breed organization permits artificial insemination (AI) with shipped semen. A mare in New

The shipping of cooled and frozen semen has opened the door to a wide variety of breeding opportunities for horse owners, providing, of course, that their breed organization permits artificial insemination (AI) with shipped semen. A mare in New York, for example, can be bred to a stallion which is standing in California and never leave her home farm or come into physical contact with the stallion.

The stallion’s semen is shipped across country inside a specially designed container that protects the life of the fragile spermatozoa whose job it is to fertilize the egg.

While the only objective in life for spermatozoa is to fertilize an egg, there are many potential roadblocks along the pathway between ejaculation and fertilization. Unless the spermatozoa are handled correctly, they will perish and both mare and stallion owner experience the frustration that comes with a barren mare.

On-the-farm artificial insemination has actually improved conception rates, but when semen is cooled or frozen and shipped to another location, other dimensions are added that threaten the success rate.

Time is often an enemy in this process.

B. W. Pickett, PhD, of the Equine Sciences Department at Colorado State University, has spent years studying and reporting on equine reproduction. He makes this comment: “Obviously, the longer stallion semen can be stored and return to fertility, the more flexibility stallion owners have in collecting and shipping semen, and the more flexibility mare owners have in selecting sires and synchronizing breeding with ovulation. Numerous investigators have stored equine semen at various temperatures and bred mares with semen stored 12 to 120 hours. Neither the concept nor recognition of the need is new.

“In 1939, (F. F.) McKenzie and associates reported successful impregnation of two mares with semen stored 20 hours. For one mare, the semen was shipped 1,912 miles. It has been reported by (W.) van der Holst that in the Netherlands, stallion semen is shipped and used to breed mares for up to five days. He reported that 87% of 68 mares bred with semen stored four to five days had foals. This is an excellent foaling rate, considering the semen was supposed to have been centrifuged, cooled to 5° Celsius (42° Fahrenheit), shipped, and was four to five days of age before use. Hopefully, these excellent results can be repeated, although I am somewhat skeptical, considering present technology.”

Thus, we can muse, there is a great potential for the shipping of semen, but much still remains to be done before we can achieve the same pregnancy rates with shipped semen, especially over a long time frame, as with that collected and used immediately on the farm. Generally speaking, the best window of opportunity for cooled, shipped semen is to inseminate a mare within 24 hours of collection.

The ultimate outcome, it would seem, justifies this continued effort to improve on cooling and shipping techniques.

In Pickett’s words, here are some of the advantages of shipping semen.

1. It eliminates the cost and stress of shipping a mare and/or foal.

2. The genetic pool is increased. For example, many times breeders will breed to a local stallion rather than incur costs of shipping the mare, because shipping her might increase the cost of the foal beyond economic feasibility.

3. The use of genetically inferior stallions will be reduced; thus, increasing the genetic merit of the breed.

4. Cash outlay for mare care will be reduced. When the mare is home, most often labor for her care is provided by family members.

5. The number of horse owners will probably increase. For example, young people, such as 4-H members, will become involved in getting their mares bred if they have a chance of raising a superior animal, providing the cost of getting the mare pregnant is not excessive.

6. Virtually everyone who has shipped mares and foals to large stallion stations, where horses come from many environments, has suffered unfortunate experiences with disease. Shipped semen greatly reduces the likelihood of disease transmission among farms.

Pickett does not overlook the disadvantages. He includes:

1. Considerable technology and skill are required to appropriately collect, evaluate, extend, and prepare semen for shipment; thus, unfortunately not everyone will be successful. Although this is listed as a disadvantage, it might very well be an advantage, because the additional skills and equipment will no doubt result in better management; thus higher fertility on the farm.

2. Considerable cost, as well as concerted effort, particularly with respect to communication, is required to be assured that semen is collected at the appropriate time, then shipped so that it will arrive at its destination just prior to ovulation of the designated mare.

3. Semen from all stallions will not be suitable for shipment, although their fertility might be satisfactory on a well-managed farm where semen is collected and used immediately.

4. Many times personnel receiving the semen will lack the technical skills necessary to appropriately handle the semen prior to, and during, insemination. To be successful, it may be necessary to ship the mare to an “insemination center.” This will negate, to some extent, one of the greatest advantages of shipped semen, i.e., the mare must be shipped, although the distance might be much shorter.

5. In many cases, reproductive management of the mare, with respect to teasing and identification of heat and synchronization of estrus with arrival of semen, will be insufficient for maximum reproductive efficiency.

“In spite of these disadvantages,” Pickett concludes, “appropriate utilization of transported semen can aid in improving the quality of our horses; thus, increasing the pleasure derived from owning a superior animal.”

There are breeders who worry that unlimited use of cooled and frozen semen might result in an excess number of foals from certain stallions, thus reducing the book for other, less-popular stallions.

Pickett disagrees with this assessment. When discussing the numbers question in regard to the use of frozen semen, Pickett had this to say: “Even with improved technology, it is unlikely that more than 35 insemination doses (straws) can be prepared from semen ejaculated by a stallion in one week, and even fewer when semen is processed during the non-breeding season. Furthermore, some insemination doses must be used to evaluate quality of the product, and many insemination doses will be unsatisfactory and, therefore, discarded. It is unlikely that more than 300 to 400 insemination doses of satisfactory semen would be obtained from a normal stallion in a 12-month period. Because most mares will be bred several times during each estrous cycle, sufficient insemination doses might be available to breed 100 to 200 mares in one year.”

When cooled semen is involved, more spermatozoa per dose are recommended than when using fresh semen–from 500 million to 1 billion.

The reason for recommending that 1 billion progressively motile spermatozoa be included in each dose of semen to be extended, cooled, and shipped is that approximately 50% of cooled spermatozoa will become non-motile during cooling and transport. Thus, if one starts with 1 billion spermatozoa, there is a strong likelihood that 500 million will still be motile when placed inside the mare’s reproductive tract.

Helping Preserve Life

Unfortunately, with some stallions the mortality rate of spermatozoa is much greater. For reasons that are not entirely clear, certain stallions produce spermatozoa that simply can’t stand the rigors of cooling and shipment.

Helping to prolong the life and motility of spermatozoa is the use of extenders which are mixed with semen. There are a number of commercial extenders on the market. The most successful, in Pickett’s opinion, are extenders that are based on a combination of powdered milk and glucose.

In enumerating the advantages of using extenders, Pickett points out that they include permitting effective antibiotic or antibacterial treatment of semen containing pathogenic or potentially pathogenic organisms; prolonging the survival of spermatozoa; enhancing viability of spermatozoa from many low-fertility stallions; protecting the spermatozoa from unfavorable environmental conditions; increasing the volume of the inseminate; and aiding in proper evaluation of spermatozoal motility.

It is important that the extender be added to the semen shortly after collection and that the cooling process for shipped semen also be initiated quickly. One recommendation is that extender be added within 10 to 15 minutes after collection and that cooling be initiated immediately after the extender is added.

The purpose in cooling spermatozoa is to slow down cellular metabolism and deterioration. The goal is to cool the semen as quickly as possible, while at the same time avoiding cold shock that can cause damage and even kill spermatozoa.

If semen is to be stored for long periods–24 to 48 hours–it must be cooled to about 5° Celsius, and that temperature must remain constant.

A private company that has been in the forefront of developing and utilizing containers to ship semen cross-country is Hamilton-Thorn. The device it features is called the Equitainer. The Equitainer provides thermal exchange conditions, plus insulation and shock protection needed for storage and shipping. The key component of the system is the isothermalizer, which provides both the correct cooling rate and the final temperature for the semen.

There are also two ballast bags that contain protective fluid and are used to maintain the correct temperature. Also included are two coolant cans that contain a special coolant used to cool the semen at a rate that will reduce cold shock. (The coolant cans must be kept in a deep freezer for at least 24 hours before use.)

Hamilton-Thorn produces a Transported Semen Handbook that provides both general information and step-by-step procedures for handling semen and placing it inside the Equitainer for shipment.

For example, Hamilton-Thorn proffers these specific suggestions for extending semen:

1. Add appropriate antibiotics to the semen extender and gently mix.

2. Add extender to semen slowly by pouring down the side of the cup, one-fourth at a time, mixing gently.

3. Normal dilution is approximately two to five parts extender to one part semen, depending on the horse’s normal concentration of semen. Ideal dilution is to 50m/ml.

4. The recommended number of total sperm to send is 1-2 billion. If the concentration of the semen is approximately 50m/ml, then the ideal volume to ship to obtain the recommended total sperm is approximately 40 ml.

5. If using a vial for shipping, be sure the vial is filled to top. If necessary, add extra extender.

Hamilton-Thorn also offers this seven-step procedure for insemination:

1. Make a positive identification of the mare by comparing her to the mare identification passport.

2. Do not warm the semen. The mare provides the best environment to warm the semen.

3. Prepare the mare for insemination. Wrap her tail and clean her thoroughly. If soap is used, be sure to rinse her well.

4. Set up all items needed for insemination, such as sterile pipette, sterile syringe, gloves, and sleeves. Remember that many types of syringes and pipettes might have a toxic effect. If yours does, or you are not sure, leave the semen in contact for as short a time as possible.

5. All of the above items should be kept at room temperature–15 to 20° Celsius.

6. Open the Equitainer and remove the packet of semen. Rotate to stir gently and carefully draw into the slightly warm sterile syringe.

7. The mare should be inseminated as soon as possible. She provides the best environment for the semen and is the best warmer

Create a free account with TheHorse.com to view this content.

TheHorse.com is home to thousands of free articles about horse health care. In order to access some of our exclusive free content, you must be signed into TheHorse.com.

Start your free account today!

Already have an account?

and continue reading.

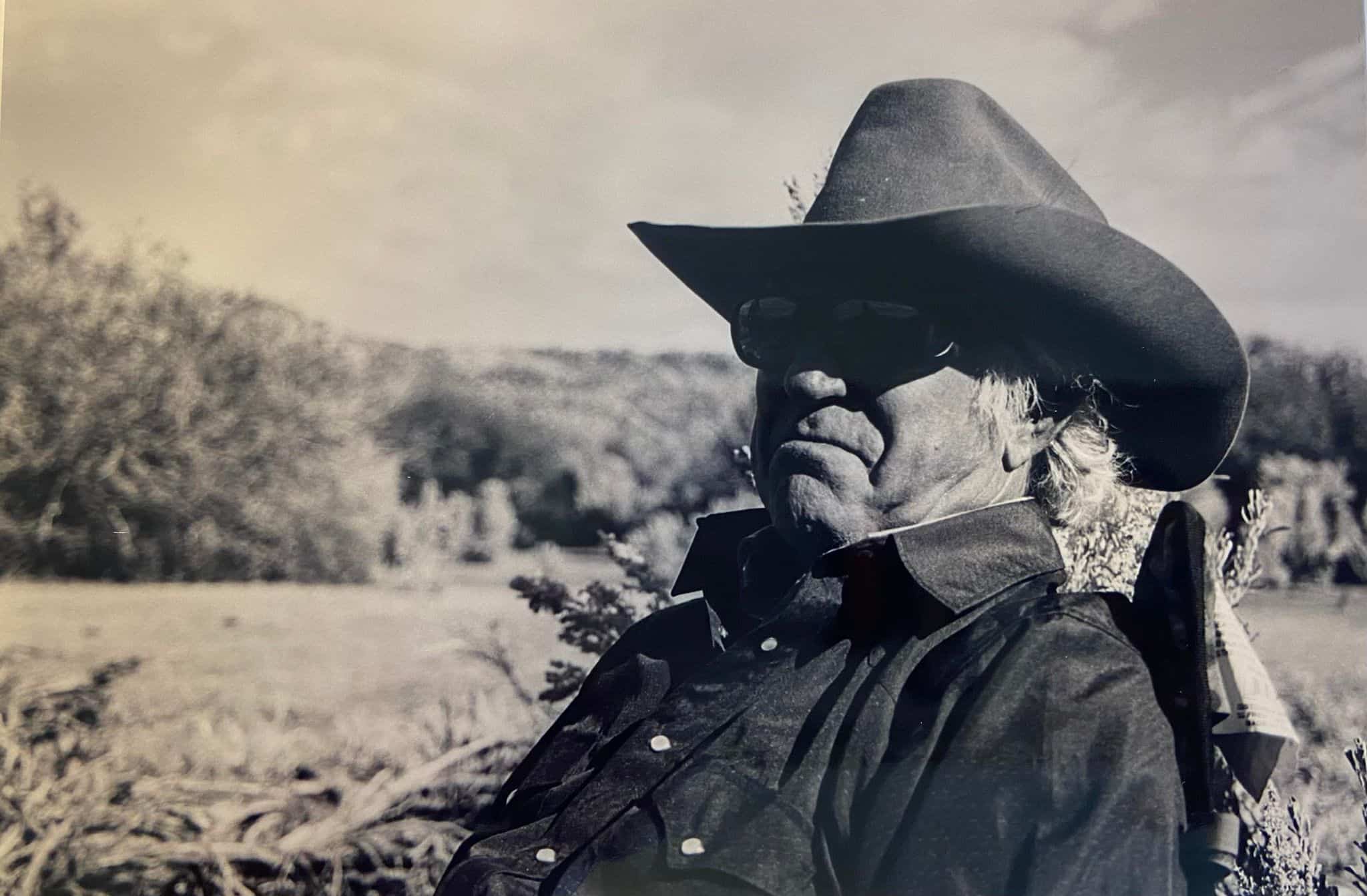

Written by:

Les Sellnow

Related Articles

Stay on top of the most recent Horse Health news with