Breeding Older Mares

As a mare’s fertility wanes, there are still steps—some simple, some cutting-edge—breeders can take to obtain a foal

She’s the kind of mare every breeder loves to have on the farm: well-built and attractive with great movement, excellent ground manners, and the uncanny ability to always produce stunning foals. And she’s a great mama, to boot. Problem is, she isn’t getting any younger, and so her fertility isn’t what it used to be. Fortunately, good management practices and veterinary advancements can help. And for that exceptional senior mare, avant-garde services add to your reproductive options when breeding older mares.

“Some older mares are quite valuable,” says Patrick McCue, DVM, PhD, Dipl. ACT. “They consistently pass on their talent, temperament, and conformation to their offspring or have cherished older genetics. Until it is very clear that these mares are done, their owners may want to try to get one last pregnancy.”

McCue heads Clinical Stallion, Broodmare, Foaling and Embryo Transfer Services at Colorado State University’s Equine Reproduction Laboratory, in Fort Collins, and handles equine reproduction cases at the school’s Veterinary Teaching Hospital.

From ages 4 to 15, mares are in their reproductive prime. But from 15 to 20, their fertility declines, says McCue. Reproductive problems only continue to intensify in mares older than 20.

Of course, each mare is an individual with her own health history and genetic tendencies. But why does mare fertility decline with age, and what can be done about it? We talked with equine reproduction specialists about common fertility and pregnancy problems in this mare demographic to get some answers.

Old Oocytes

Unlike most stallions, who can produce fresh sperm all their lives, a mare is born with all the oocytes, or immature eggs, she will ever have. (That’s pronounced O-uh-sites, by the way, if you’re talking to your equine reproduction specialist.) So basically, if a mare is 20 years old, her ovarian follicles, each of which contains an oocyte, are also 20 years old, says McCue.

These oocytes then wait, suspended at a specific stage of meiosis, or cell division. Being stuck in that stage for years can take its toll, he adds. They might suffer a few defects that will make them less fertile.

Cycling Abnormalities

Mares are seasonal breeders, meaning they only cycle naturally during a particular time of year so that they will deliver foals, ideally, in temperate weather.

In the winter darkness, a mare’s ovaries are inactive. It’s a period called anestrus. Increasing amounts of daylight in spring trigger the normal healthy mare’s reproductive cycle. It spurs it to life in what’s called the vernal—from vernalis, derived from ver, the Latin word for spring—transition into the breeding season.

Each mare is different and the time of year causes some variation, but there is a basic estrous pattern, or cycle, of 21 days from one ovulation to the next. This pattern is divided into diestrus, when the mare is not receptive to breeding, and estrus or “heat,” when she is.

When a mare is in heat, which lasts four to seven days, the oocyte develops within its follicle, a fluid-filled sac of cells that protects and nourishes it. The enlarged follicle ovulates or releases the egg about 24 to 48 hours before the mare transitions back to diestrus.

From there the oocyte travels into one of the oviducts—two tiny tubes that stretch from the ovaries to the horns of the uterus—where fertilization should occur. The fertilized egg, now called an embryo, then stays in the oviduct about six days before entering the uterus. Then it travels through the uterus until it becomes fixed, about 16 days after ovulation.

Older mares might begin cycling later in the spring than younger mares, and the time between ovulations might lengthen. Problems can arise with ovarian follicle development, resulting in a longer time in the follicular phase and smaller follicles from a slowed growth rate.

Dr. Carlos Pinto

McCue says the incidence of ovulation failure increases with age. For young mares, the dominant follicle (the one that grows fastest in preparation for ovulation) fails to ovulate in less than 5% of cycles. But when mares are 15 and older, that rate can increase to 13%.

“Some older mares have very irregular cycles,” says Carlos Pinto, MedVet, PhD, Dipl. ACT, associate professor and chief of the theriogenology section at Louisiana State University’s School of Veterinary Medicine, in Baton Rouge. “It is not uncommon to see mares above 20 years of age that take three to four weeks or longer to build a follicle suitable for breeding. Even if they ovulate, there is a question of how normal the corpus luteum is to produce adequate amounts of progesterone to maintain a pregnancy.”

That corpus luteum, a temporary structure that forms on the site where the ovum is released, secretes the steroid hormone progesterone needed to establish and maintain a pregnancy. If the mare’s body recognizes a pregnancy, it produces more progesterone. If there is no embryo or there is but the mare’s body fails to detect it, the uterine lining releases the hormone prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α), which destroys the corpus luteum and stops progesterone production.

Endometrosis

Because of their age, mature mares have had more opportunities to experience a decline in uterine health. Scar tissue could have developed as could endometrial cysts, which can present problems if they become large or are plentiful.

These chronic degenerative changes in the uterine lining, or endometrium, are known as endometrosis, says Pinto. As a co-author on a study published in the October 2015 issue of Theriogenology, he discovered reduced blood flow in the uterus during early gestation in older mares as well as in those with significant endometrial degeneration.

“Less blood flow is thought to indicate less interaction and exchange in the so-called embryo-endometrium talk,” he says. “Endometrosis may be one of the factors leading to less blood flow, and we don’t have a treatment for that (yet).”

Is It Worth the Cost?

Be aware that breeding an older mare can be expensive. While prices vary, here are a few to consider before you embark on the venture:

- $300-$600 for a reproductive evaluation;

- $200-$500 for subfertility management;

- $500-$800 for embryo flushing;

- $300-$5,000 per embryo transfer attempt;

- $3,000-$6,000 for leasing a surrogate (recipient) mare;

- $1,500-$3,000 for care of the recipient mare;

- $1,250 per session for sperm preparation/ICSI; and

- $2,000 per line and $1,000 for each additional line (more than one is recommended) to process tissue for cell culture and cryopreservation.

—Maureen Blaney Flietner

Acute or Chronic Endometritis

An important cause of embryo loss during early gestation is persistent post-breeding endometritis. The primary problem associated with endometritis is poor evacuation of the uterus, or clearance of debris or other foreign material, which then produces a persistent endometrial inflammation (hence, the -itis).

All mares develop a temporary uterine inflammatory response after breeding because of the spermatozoa and, inevitably, bacteria introduced. Typically, the fluid pushes out and the inflammation resolves on its own, says Pinto.

But the older mare might lose her ability to evacuate that material. Instead, the inflammatory fluid can remain there for days and lead to a secondary infection and chronic endometritis. This results in a uterine environment that is incompatible with embryo survival, says McCue.

Oviduct Issues

Another reproductive problem occurs in the oviducts, says McCue, which are lined with hairlike cilia that transport the egg and sperm.

An accumulation of debris, such as cells and fibrin strands from previous ovulations or pregnancies, can block these tubes and prevent the egg, sperm, or developing embryo from passing.

Anatomical, Acquired, or Age-Associated Changes

Then there’s the mare’s body, which sustains wear and tear over time. Pinto says problems might include worsening perineal conformation, such as vulvar defects, vulvar slope, urine pooling in the vagina (also known as vesicovaginal reflux), and windsucking, as well as cervical defects.

Advanced age can bring “progressive tilting forward of the upper part of the vulva over the pelvic brim that may significantly affect the ability of a mare to become pregnant or remain pregnant,” says McCue. Poor body condition can exacerbate this.

Common Ways to Improve Fertility

Over the past several decades veterinarians have determined that certain practices can increase an older mare’s fertility. These include:

“We have published on how teasing—even when the mare hears the stallion approaching—favorably contributes to myometrial activity,” he says. The myometrium is the smooth muscle tissue of the uterus. “Thus, mares without direct contact with stallions may have impaired uterine activity to clear the uterus after artificial insemination.”

This is why veterinarians commonly treat mares with drugs that stimulate myometrial activity (oxytocin, PGF2α).

Caslick’s operation This tried-and-true surgical procedure, which involves sealing the upper part of the vulva with sutures, corrects a problem mentioned earlier—windsucking, which is when the vulva allows air into the vagina and no longer acts as a barrier against contamination and resulting infection. The surgeon must remove the sutures before breeding (and resuture them after) and about 30 days before the expected foaling date to avoid damaging the reproductive tract.

Ovulation-inducing agents One technique that can help prevent endometritis, says McCue, is the administration of an ovulation-inducing agent to help direct when ovulation will occur. Veterinarians can then optimize timing for insemination, uterine lavage, or oxytocin administration after breeding to remove any accumulated uterine fluid, and administration of progesterone to help support the ensuing pregnancy.

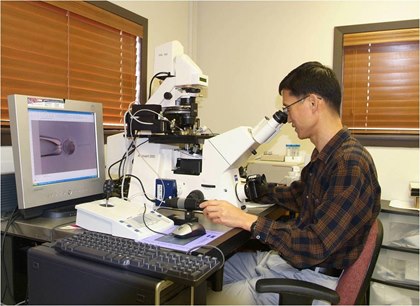

Oocyte transfer During this procedure, which is useful for older mares that can no longer produce embryos, the veterinarian sedates the mare in heat and passes a special ultrasound-guided probe with a 12-gauge needle through her vaginal wall and into her ovary to aspirate the oocyte and follicular fluid from a pre-ovulatory follicle. The oocyte might be transferred immediately into a recipient mare’s oviduct via laparotomy (an incision into the flank) or cultured in a laboratory before transfer. The recipient mare must either be cycling or treated with hormones to mimic a natural cycle. The veterinarian then inseminates that mare. The success rate of oocyte collection from donor mares is around 70% to 80%. Pregnancy rates after transfer are 40% or more.

Embryo transfer This service, useful for mares with reproductive disorders that prevent them from carrying foals to term or who are too old to risk delivering, requires two main procedures, says Pinto. One is the embryo collection, performed nonsurgically by catheterizing the uterus to “flush” the uterine horns. Embryo recovery rate is about 75% but as low as 10% to 20% in subfertile mares. The second is the embryo transfer procedure, during which the veterinarian deposits the embryo into a surrogate mare’s uterus.

Hormone application If a veterinarian suspects blocked oviducts, he or she can apply a hormone, such as PGE2-laced triacetin gel, directly to the oviducts’ smooth muscle surface to relax it. Pinto says this procedure is relatively uncommon and mainly performed in specialty clinics because of the laparascopic approach necessary, and he notes the success rates for older mares are low.

Improved Reproductive Technology

In recent years the tools and assisted reproductive techniques available to veterinarians trying to get older mares pregnant have improved greatly.

“There are better ultrasounds for detailed visualization, (in addition to) the ability to culture materials from the uterus, advanced molecular biology techniques to detect infectious organisms, medications now tested for efficacy in the uterus so we know how they work, pharmacokinetic studies, and more diagnostic and therapeutic options,” says McCue.

Because these technologies are expensive and time-consuming, mare owners need to be aware of their success rates and determine if possible offspring justify the attempt. And before selecting an approach, be sure your particular breed registry permits it.

Katrin Hinrichs, DVM, PhD, is regents professor and Patsy Link Chair in Mare Reproductive Studies in the Department of Physiology & Pharmacology at Texas A&M University’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, in College Station. Hinrichs, along with her research group, cloned the first horse in North America and the third in the world. She describes some of the high-tech breeding services owners faced with declining mare fertility might pursue.

Cell line processing (tissue culture and freezing to save DNA for cloning) “Cloning will produce another filly with the same genetics as the original mare, and this filly can be bred throughout her lifetime,” says Hinrichs. “Although cloning is expensive (upwards of $85,000), the ability to breed for 15-20 years using standard reproductive management makes this a cost-effective approach overall.”

Many breed associations will not register clones or their offspring. For instance, the American Quarter Horse Association recently won a legal battle on the subject and will not have to register clones. However, some stud books, such as Zangersheide in Europe, will register cloned horses.

Oocyte recovery from mares that are dying or will be euthanized This is a final chance to produce foals from a valuable mare. The veterinarian removes the ovaries from the mare just before or immediately after death or euthanasia and handles the oocytes similarly to those recovered from live mares.

Embryo vitrification This method of cryopreserving (freezing) embryos extends the breeding season for older mares. These mares often only cycle toward the middle of the natural breeding season, says Hinrichs. But some breed registries offer futurities in which horses compete against others their own age, so foals born late in the year might be at a competitive disadvantage.

Using this method, embryos collected in the late summer or fall can be cryopreserved and then transferred in the spring.

“With embryo vitrification, the older mare can be used for embryo recovery throughout the time she is cycling and for oocyte aspiration for ICSI throughout the year,” says Hinrichs. “Mares do not have to be actively cycling to have follicles that can be aspirated for ICSI.” The chance of a successful pregnancy decreases by 10% to 25% when embryos are frozen.

Take-Home Message

Treat each older broodmare as an individual, work with a good veterinarian, learn about possible problems, and practice good management. For instance:

- Before committing to a breeding program, schedule a reproductive exam to find out if your mare has any issues.

- Stay on top of general herd health and the health of the older mare. That includes vaccinations, deworming, nutrition, and dental care so she can maintain her body condition, says McCue.

- Realize that breeding an older mare might require extra attention to details and more services. The mare needs to ovulate on schedule and likely requires post-ovulatory exams and uterine lavages.

- Consider any arthritis, lameness, nutritional, or overall health issues the mare has. Decide whether you want to consider assisted reproductive techniques.

- If genetics are very important and there’s a chance the mare won’t carry to term, consider embryo transfer, says Pinto.

Written by:

Maureen Blaney Flietner

Related Articles

Stay on top of the most recent Horse Health news with