PPID and Laminitis in Horses: What’s the Relationship?

At the 2018 American Association of Equine Practitioners Convention, a U.K.-based equine practitioner shared some startling statistics on pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID, or equine Cushing’s disease) and the hoof disease laminitis:

- Horses with PPID are at least four times more likely to have laminitis than those without PPID.

- Many times, horse owners don’t realize horses are suffering from laminitis.

- Horses with PPID that also have uncontrolled insulin are less likely to survive the next two years compared to those with controlled insulin concentrations.

Therefore, understanding the intersection between PPID and laminitis is an important welfare issue, said Cathy McGowan, BVSc, Dipl. VetClinStud, MACVSc, PhD, Dipl. EIM, ECEIM, FHEA, MRCVS, head of the equine clinical science department and director of veterinary postgraduate education at the University of Liverpool Philip Leverhulme Equine Hospital. She presented a review of the topic at the convention, held Dec. 1-5 in San Francisco, California.

Laminitis Background

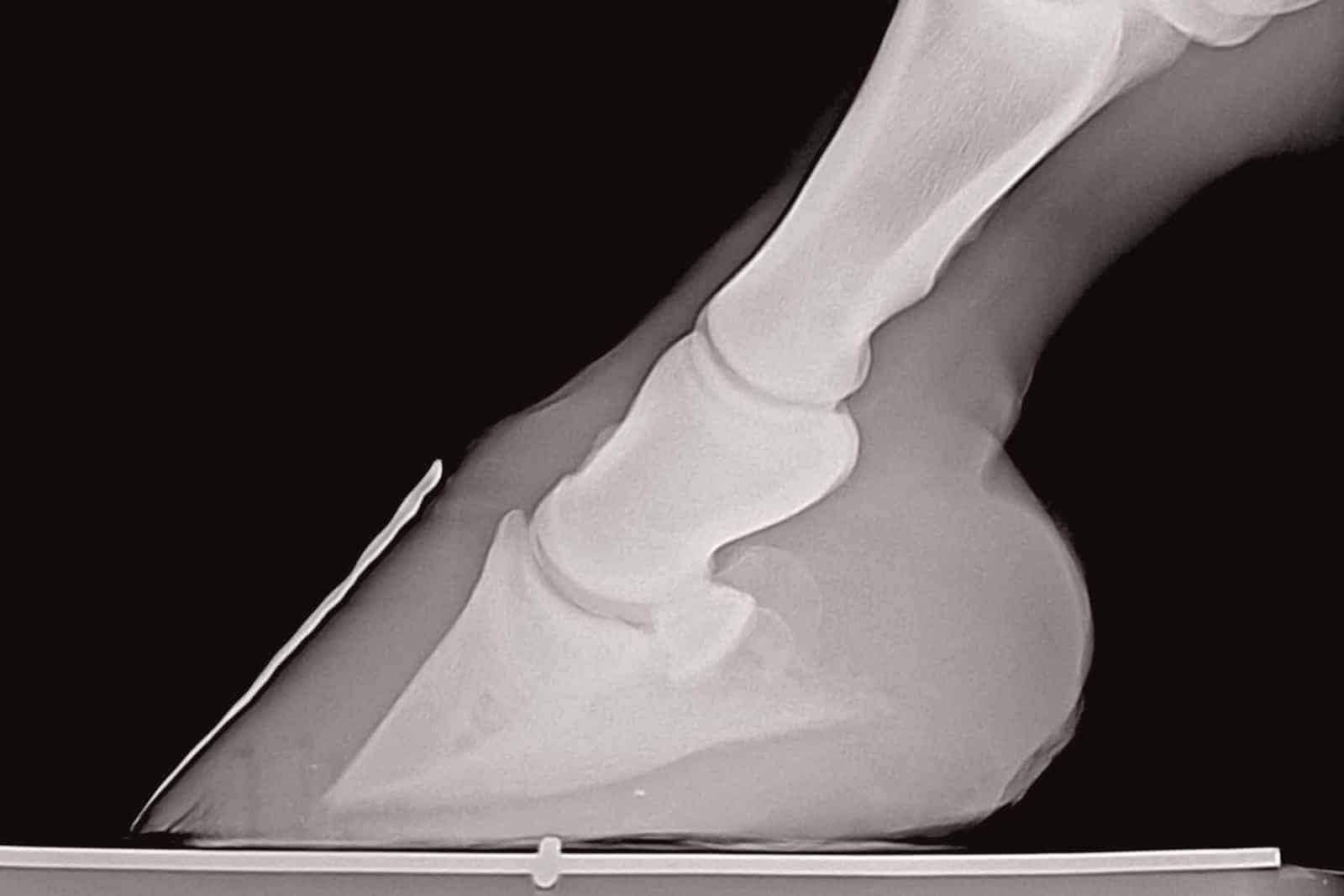

Laminitis occurs when the laminar tissues suspending the coffin bone within the hoof capsule fail. There are three types of cases: systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS, a cascade of body-wide inflammation that can leads to laminar failure in the hoof) laminitis, supporting-limb laminitis, and endocrinopathic laminitis. Historically, researchers focused most on SIRS-associated laminitis, she said due to this being the most commonly seen form of laminitis in university hospitals where research was conducted. However, in recent years, researchers in Europe and the U.S. have confirmed that 90% of horses with laminitis have an endocrine disorder while other research has shown that infusion of insulin in healthy ponies leads to laminitis. As a result of this, and other supporting work, much of todays’ laminitis research is focused on the endocrinopathic form.

Both PPID and equine metabolic syndrome (EMS) are associated with insulin dysregulation (ID) which is thought to be the underlying factor in endocrinopathic laminitis. Horses with ID have either elevated baseline circulating insulin or an exaggerated insulin response to nonstructural carbohydrates in their diets.

Commonly diagnosed in aged horses, PPID develops when a horse’s hypothalamus and pituitary gland—located at the base of the brain—fail to communicate appropriately, causing the pars intermedia (a lobe in the pituitary gland) to produce more hormones (including adrenocorticotropic hormone, or ACTH) than it should. This results in the clinical signs of PPID: excessive hair growth, not shedding properly, muscle wasting, increased susceptibility to bacterial infections, behavior changes, abnormal sweating, polyuria (excessive urination), infertility, exercise intolerance, and ligament or tendon injuries, McGowan said.

On the other hand, EMS is defined as a phenotype (observable characteristic) of ID and (usually) obesity. It can predispose horses to laminitis in the absence of SIRS- or supporting-limb-laminitis-related factors, she said.

How PPID Relates to Laminitis

Veterinarians frequently diagnose laminitis in horses with PPID—researchers have shown it to be the second-most-common PPID clinical sign after excessive hair growth, McGowan said. Insulin dysregulation appears to be a key component of laminitis development in PPID horses, she said. In fact, researchers have seen lesions in the laminar tissue in PPID horses with ID that don’t always exist in PPID horses with normal insulin regulation.

Study results have shown that horses with PPID are 2.7 times more likely to have hyperinsulinemia (high blood insulin levels) than horses of the same age without PPID. However, McGowan cautioned, all aged horses with hyperinsulinemia are at risk of developing laminitis.

She said researchers have been trying to understand how hyperinsulinemia leads to laminitis for some time. When working properly, insulin stimulates vasodilation (widening of the blood vessels) and blood flow. However, they’ve learned the opposite happens in horses with insulin resistance. Researchers have observed vasoconstriction in horses suffering from endocrinopathic laminitis.

But, as it turns out, this is not the whole picture, McGowan said—endocrinopathic laminitis isn’t just an issue of altered blood flow. Hyperinsulinemia also affects the epithelial cells that make up the laminae in the hoof. In horses with ID, high circulating insulin appears to disrupt how laminar cells signal each other. This results in activation and disruption of certain pathways and “downstream” events within the cells leading to damage and disruption of the cytoskeletal organization. This microscopic network of protein filaments in the hoof begin to stretch and elongate under mechanical forces. Initially, this might not cause pain, but marked elongation is visible as soon as six hours after hyperinsulinemia sets in. This means hoof tissue damage is occurring even though clinical signs of laminitis aren’t yet apparent.

The Bottom Line

While researchers are currently investigating several mechanisms, it is not yet clear how PPID leads to ID and, subsequently, laminitis. What we do know, however, is that regardless of how PPID horses develop ID, having both conditions leads to a poorer prognosis than having either condition alone, McGowan said.

Further, because researchers have shown that endocrinopathic laminitis accounts for about 90% of laminitis cases seen in the field, it’s important to keep tabs on your own horses.

Owners, veterinarians, and farriers should check the hooves of horses with PPID for signs of subclinical (inapparent) laminitis, regardless of whether they have a history of laminitis. And, veterinarians should check PPID horses’ insulin regulation and use test results to guide long-term management.

Finally, horses with ID-induced laminitis require hoof support as soon as possible during treatment, and the owner and veterinarian should take steps to reduce circulating insulin concentrations through management techniques such as feeding low non-structural carbohydrate hay and feeds, reducing or eliminating turnout time on grass, and soaking hay if necessary.

Editor’s Note: This article is part of TheHorse.com’s coverage of topics presented at the 2018 American Association of Equine Practitioners Annual Convention, held Dec. 1-5 in San Francisco, California.

Written by:

Clair Thunes, PhD

Related Articles

Stay on top of the most recent Horse Health news with