Interpreting Imaging of the Equine Neck

Neck pain and dysfunction in horses can be related to bony or articular lesions (e.g., osteoarthritis, intervertebral disk degeneration), soft tissue (e.g., myofascial pain, synovitis), or neurologic conditions. “Articular process joint osteoarthritis is considered the leading cause of neck pain and stiffness in horses,” said Kevin Haussler, DVM, DC, PhD, Dipl. ACVSMR, associate professor at Colorado State University’s Orthopaedic Research Center, in Fort Collins, during his presentation at the inaugural American College of Veterinary Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation Symposium held April 27-29 in Charleston, South Carolina. In his talk, Haussler reviewed the anatomy of the cervical articular processes, the spectrum of osteoarthritis within those spaces, and how to determine the clinical relevance of imaging findings.

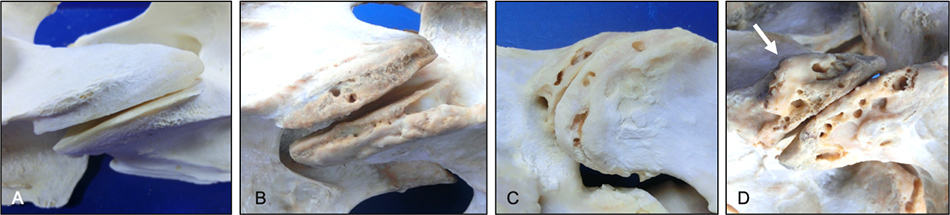

Osteoarthritis is a disease of the entire synovial articulation—in other words, the two bones coming together at the joint, the cartilage where they meet, and the synovial membrane and fluid within it. Haussler said it can be described as a spectrum because, although diagnostic imaging can easily detect some changes, it can’t pick up on others. The complex anatomy of the cervical articular processes and superimposition of the structures can make diagnostic imaging challenging for veterinarians, he said, adding that horses often have a combination of soft tissue and osseus changes present.

Researchers have reported osseous changes occur in about 50% of horses deemed clinically normal and, often, horses display a combination of normal and diseased articulations within their neck, Haussler said. “Two-dimensional imaging is used to diagnose a three-dimensional problem, which causes problems with establishing a proper diagnosis,” he added, referring to the nature of radiographs. Some horses might experience severe pain and performance issues with no detectable physical abnormalities, while others have significant bony abnormalities that do not appear to cause pain.

In a study of eight horses euthanized for severe neck pain, investigators deemed 86% of the horses had normal cervical radiographs, said Haussler. However, they found only 3% of those horses to have normal cervical anatomy based on observed bony changes at necropsy.

A wide range of bony changes can occur in the articular processes, and it is important to identify exactly where. Often veterinarians must use multiple diagnostic imaging modalities, including computed tomography, myelography, and ultrasonography, to create a more complete picture of the horse’s anatomy and to determine the possible sources of pain.

Clinical relevance of the imaging findings varies based on the clinical signs and the horse’s pain and stiffness. “When there are combined osseus and soft tissue changes, we have to ask, ‘Which findings are most relevant?’ and ‘What do we do when we find these changes?’” he said.

When the clinical relevance of diagnostic images is unclear, Haussler said veterinarians should consider the horse’s movement patterns, athletic use, and overall performance to determine an appropriate treatment plan.

Written by:

Haylie Kerstetter

Related Articles

Stay on top of the most recent Horse Health news with