Equine Meniscal Injuries

If a veterinarian suspects a horse has a meniscal injury, the first two steps in the diagnostic process include a physical examination, followed by a lameness evaluation. Ultrasound and radiography are the best diagnostic imaging options for meniscal injuries on the farm, but MRI, CT, and exploratory are also useful.

“Ultrasound can help veterinarians look at the soft tissue structures within the limb,” said Garcia-Lopez. Radiographs allow veterinarians to examine soft tissue insertion points, potential osteoarthritis in the joint, subchondral bone cysts, and joint collapse, which can help them make a more accurate diagnosis. “It is not one diagnostic method versus the others,” added Garcia. “Each has their pros and cons, but when used together, they can give us a comprehensive view of pathologies (disease or damage) in the stifle area.”

Exploratory arthroscopy is the diagnostic method of choice when veterinarians suspect a meniscal injury but have not localized the lameness to the stifle. They often use this method when other diagnostic test results are inconclusive, no other abnormalities are found in the stifle area, and medical management has not been effective.

In non-equids, meniscal injuries are caused by crushing forces with rotation; however, in horses crushing forces during hyperextension lead to damage to the meniscus. For example, when a horse transitions into the canter, he pushes off the ground, which is often when the stifle area experiences crushing forces and the largest degree of translocation of the cranial horn of the media, said Garcia-Lopez.

Once diagnosed, meniscal injuries fall into three categories:

- Grade 1: partial tear in the cranial meniscotibial-ligament.

- Grade 2: complete tear of the meniscotibial-ligament, where the limits of the tear are visible.

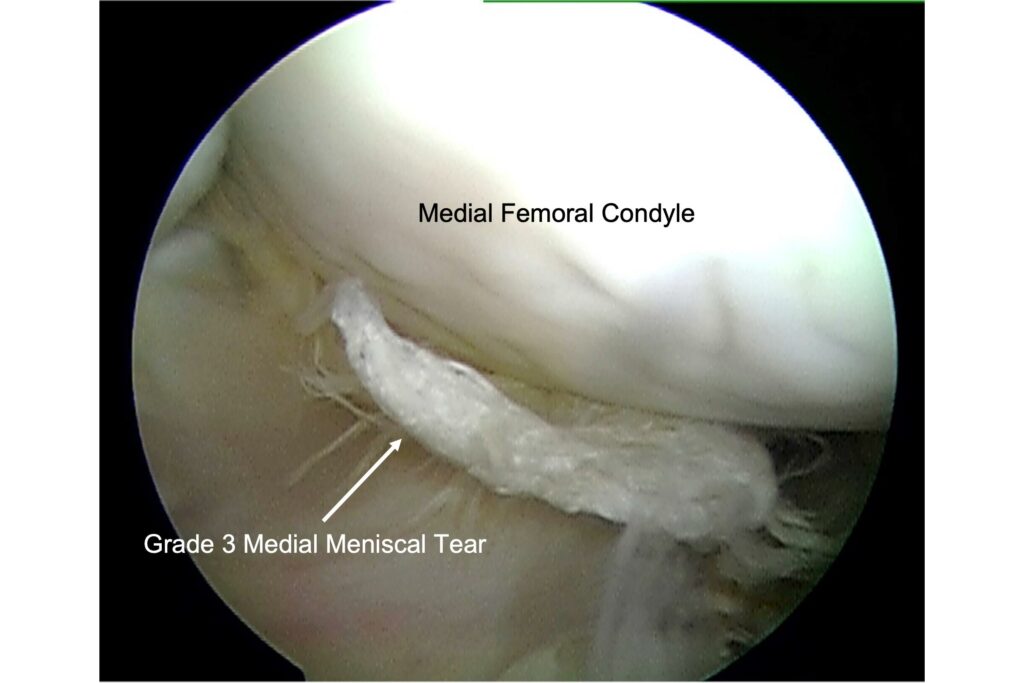

- Grade 3: severe tear of the meniscus and meniscotibial ligament that extends beneath the femoral condyle and does not have visible limits.

In surgical cases, postoperative care is crucial to the horse’s future soundness. Garcia-Lopez recommended a regimen of polyglycan immediately after surgery and in the two to six weeks following. Orthobiologics such as interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein (IRAP) and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and intramuscular Adequan treatments can make a successful recovery more likely, said Garcia-Lopez.

“I create an individualized rehabilitation plan for each horse based on the degree of the injury,” he said. “I use a mix of aggressive and conservative rehabilitation, modified based on recheck examinations and repeat ultrasound exams every six to eight weeks.”

The prognosis for horses with meniscal injuries greatly depends on the degree of injury. In a recent retrospective study looking at the long-term prognosis of 76 sport horses undergoing arthroscopic exploration for management of meniscal injuries, 86% of the horses returned to work. Although horses with Grades 1, 2, and 3 injuries to the medial meniscus returned to work in 82%, 100%, and 87.5% of the cases, respectively, only 48.7%, 37.5%, and 0% returned to their previous level of work.

Written by:

Haylie Kerstetter

Related Articles

Stay on top of the most recent Horse Health news with