Fall Foresight: Seasonal Preventive Horse Care

- Topics: Air Quality, Article, Barn & Stall Equipment, Basic Care, Cushing's Disease, Deworming & Internal Parasites, Farm and Barn, Hay, Healthy Farm Management, Hoof Care, Horse Care, Nutrition, Pasture & Forage Management, Pasture Equipment, Seasonal Care, Shoeing, Vaccinations, Water & Electrolytes

Autumn is the time for preventive horse health care and winterizing equine facilities

As you put away your warm-weather clothes in preparation for the cooler days ahead, you also need to be taking steps to prepare your barn and meet your horse’s needs before the weather turns bad. Check off this list of must-do tasks when putting your preparations in place.

1. Check your water system and heater

Ample water intake is essential for normal bodily and digestive functions and to reduce the risk of impaction colic, particularly in winter. The average horse needs to take in 5 to 10 gallons of water per day in cold climates, says Holly J. Helbig, DVM, of Hawthorne Veterinary Clinic, in Dublin, Ohio.

“Your horse consumes the maximum amount of water when it’s lukewarm,” she says. “Research shows that horses drink about 40% less water when it’s close to a frozen state. One option is to use heated water buckets that are easy to hang and relatively inexpensive compared to installing automatic waterers or tank heaters. If your horses live outside in the winter, a heated water tank is an excellent option but (like buckets) should be cleaned on a regular basis. The key to ensuring available water in the winter is to start early and be prepared.”

She urges property owners to check wiring and plumbing in the fall by giving everything a test run. “You don’t want to be stuck in the cold and snow trying to provide adequate water to your horses,” she says. “I’ve been there, hauling water from a house bathtub down to the barn … it’s not fun.”

Also remember to unhook your hoses from water spigots before freezing temps hit. If your farm doesn’t have a frost-free hydrant that drops below ground-freezing levels, consider having one or more plumbed into your system.

2. Care for your equipment properly

Don’t forget to perform routine maintenance on your tractors, trailers, and hauling vehicles prior to winter so they work efficiently when needed most (e.g., for a midwinter veterinary emergency or when access ways need clearing).

3. Acquire and store hay

You’ll want to put up sufficient hay to accommodate all your horses until the next year’s first cutting becomes available.

“Horses have very small stomachs—a 2-4-gallon capacity—in proportion to their overall size,” explains Helbig. “They continuously release gastric acid unlike humans, who only release gastric acid when they are hungry or eating. Due to this dynamic, horses do best when fed free-choice hay if not fighting obesity. A mature horse eats 2-2.5% of its body weight a day, equivalent to 20-25 pounds of hay for a 1,000-pound horse.”

Calculate your hay needs and buy your supply early to avoid quality and price fluctuations that can occur in winter.

“The type of hay you purchase depends on the nutritional demands on your horse,” says Helbig. “There is no ‘one size fits all’ when choosing hay, but in all cases it should be of good quality to avoid having to supplement the diet; this saves you money in the long run. You can use your basic senses to make an educated decision as to what is quality: Look for a green color (no sun-bleaching or dark areas of mold), smell for sweetness (no moldy odor), and feel for excess heat or moisture. You can also have hay analyzed by a laboratory to determine its true nutritional value.”

Ideally, store your hay off the ground in a dry and covered environment to prevent mold growth, says Helbig. “Stack bale layers in alternating, interlocking fashion,” she says. “To increase air flow, stack at least the bottommost layer of bales on their cut sides, such that baling twine doesn’t touch the floor.”

4. Assess barn air quality

In many cases barns are closed up in winter to preserve warmth, but this can exacerbate equine respiratory issues. “Horse barns need air exchange to remove moisture, prevent condensation, and provide fresh air,” says Helbig. “Proper ventilation is crucial to keep horses healthy, free from allergies and infectious respiratory diseases, and to minimize exposure to environmental irritants.”

Dr. Scott Weese

During winter an optimal ventilation rate per stabled horse is 12-19 liters per second (25-40 cubic feet per minute), she says. While this is difficult to measure, she suggests a few pointers to achieve a healthy ventilation rate:

- Multiple small air outlets create better ventilation than one large opening at the end of the aisle.

- Proper insulation of the roof and walls keeps the barn warmer in the winter and cooler in the summer and helps eliminate moisture accumulation and condensation.

- Avoid using a leaf blower to clear debris from the aisle, as this stirs up irritants.

- Remove horses from the barn when mucking stalls and sweeping (or raking) aisles.

- Don’t store hay above stabling areas.

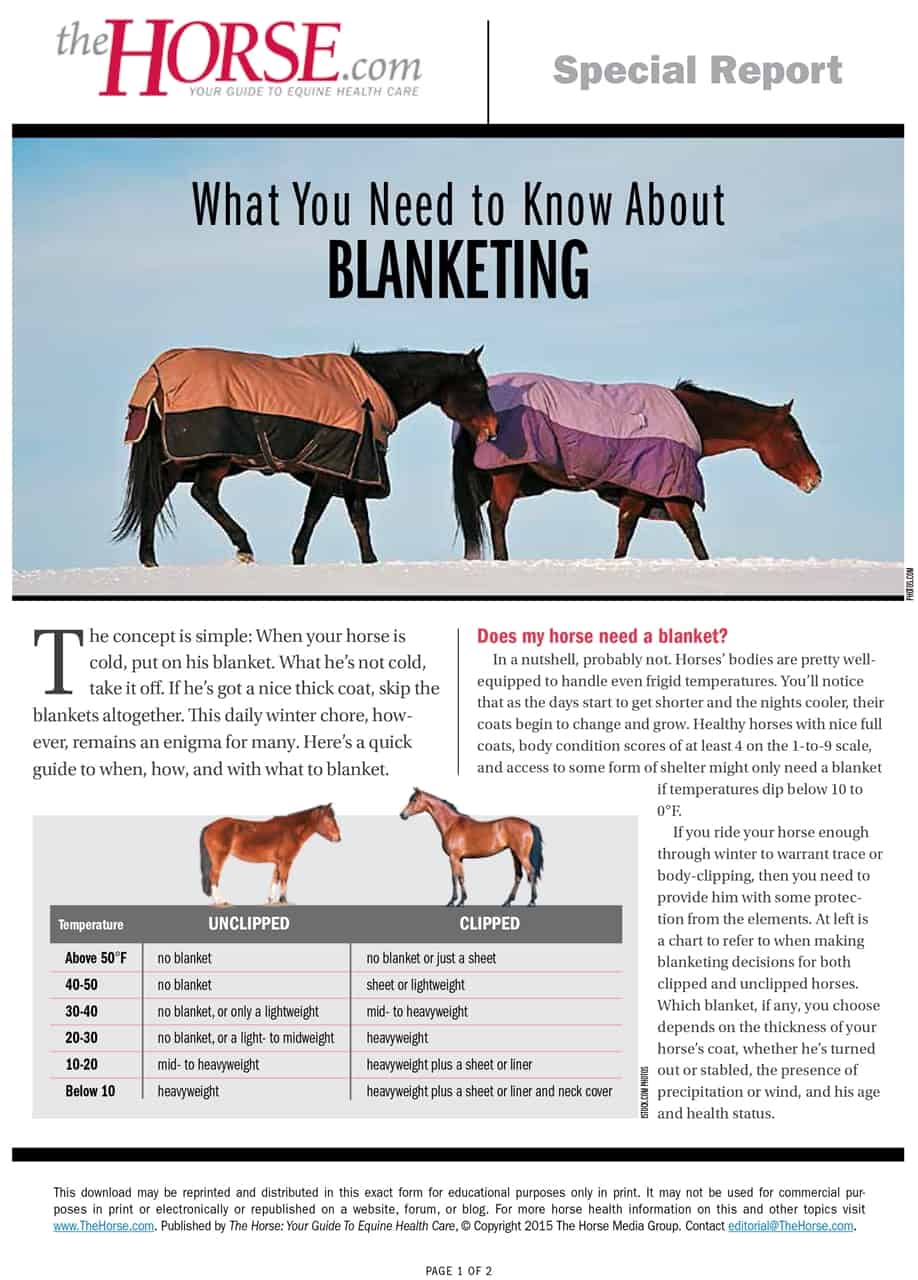

5. Check blankets

“Blanketing depends on the horse’s environment and workload,” Helbig says. “Is the horse body-clipped, trace-clipped, or completely grown out? Horses don’t recognize temperature changes until approximately 40 degrees F, at which point their body naturally starts to acclimate. You can then decide to blanket or not.”

Remember, if you begin blanketing before your horse grows out a full winter hair coat, you must be committed to blanketing through the winter.

Before placing blankets in an accessible place for ease of use, make sure they are clean and in good repair.

6. Complete a preventive care checklist

Keep vaccines up to date Chrissie Schneider, DVM, MS, Dipl. ABVP Equine, senior equine professional services veterinarian for Merck Animal Health, in Columbus, Ohio, stresses that where a horse lives and his specific disease exposure dictate which vaccinations he should receive in the fall. She recommends conferring with your veterinarian about which vaccines to give based on your horse’s individual risk.

“The decision to boost mosquito virus vaccines (EEE, WEE, and WNV) in the fall depends on the length of the mosquito season in your area or where your horse will be traveling,” she says. “Potential exposure to transient horse populations—at boarding facilities, clinics, show environments—increases risk of (exposure to and infection with) equine herpesvirus (EHV-1, EHV-4) and equine influenza virus (EIV) that are spread horse to horse through respiratory secretions. Respiratory vaccines are usually boosted spring and fall. Pregnant mares require an individualized vaccine schedule based on the expected foaling date; their EHV-1 booster vaccines usually coincide with the fall time of year.”

She adds that diseases such as rabies are year-round risks, and all horses should receive their core rabies vaccine once a year. “Some prefer to give the rabies booster in the spring along with the rest of the spring vaccines,” Schneider says. “Some prefer to give it in the fall to decrease the number of vaccines given in spring. Either approach is reasonable because horses can be exposed to rabid wildlife any time of year.”

Another pathogen (disease-causing organism) horses can be exposed to anytime is a toxin produced by the soil-dwelling Clostridium botulinum bacterium. Typically horses get exposed to the toxin by ingesting decaying forage or feed contaminated with animal remains. Rarely, they are exposed through wound contamination. Botulism vaccine boosters might be appropriate in the fall because owners tend to feed more hay—especially round bales that, if not stored properly, are more prone to contamination and spoiling—in winter, says Schneider.

Carry out fecal egg counts Deworming strategies are best applied based on a horse’s individual fecal egg count (FEC), says Helbig. Schneider adds that strategic deworming—deworming high shedders more often than low shedders—is vital to slow down the rate of intestinal parasite resistance to deworming medications. Your vet can collect fecal samples in the fall and advise you on proper deworming protocol for your horses.

Implement deworming strategies “In most areas of the USA, it is ideal to deworm all adult horses in late fall, regardless of whether their FEC indicates they are low, moderate, or high shedders,” says Schneider. Ask your vet when to deworm.

Fall, however, is a strategic time to deworm, because horses will have accumulated parasite burdens over the course of the spring and summer grazing seasons. Veterinarians typically recommend an effective dewormer (e.g., ivermectin, moxidectin) against small strongyles and praziquantel—available in combination with ivermectin or moxidectin—against tapeworms.

Deworming recommendations for horses younger than 3 differ from those for adult horses and need to also target ascarids (roundworms) that pose concerns for foals, weanlings, and young horses, she adds. Fenbendazole is the current dewormer of choice against ascarids.

Schneider recommends using a weight tape to dose your horse based on body weight. She also stresses the importance of conferring with your vet about your deworming strategy.

Clean your male horse’s sheath Sheath cleaning can be done any time of year, and many owners conveniently pair it with a dental exam and floating to take advantage of sedation. “Thorough cleaning is facilitated when a horse descends his penis outside the sheath due to sedation,” Schneider explains. “This also enables visual examination to look for tumors in the external genitalia of your gelding or stallion. In the sheath and penis, gray-coated horses tend to develop melanomas (cancerous tumors) while squamous cell carcinoma (a type of skin cancer) develops in horses lacking pigment, like many Paints and Appaloosas.”

Helbig says she cleans sheaths yearly in spring but prescribes a follow-up fall cleaning for horses predisposed to accumulating excess smegma—often associated with tail rubbing—or cancerous lesions.

Test for pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID, aka equine Cushing’s disease) The pituitary gland produces adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) that stimulates cortisol release from the adrenal gland. In the fall, the amount of ACTH horses’ bodies produce increases temporarily in what’s called a “seasonal rise.” Helbig says in her experience, this increase is relatively small and doesn’t cause problems for most horses. However, for older horses or individuals in early stages of PPID, it can lead to an initial bout of the painful hoof disease laminitis during the fall months.

“There are multiple tests available for diagnosis of PPID,” Schneider explains. “Currently, the most widely used diagnostic test measures ACTH.”

Vets used to avoid testing horses with suspected PPID in the fall because of that normal seasonal rise. However, she says, “research has shown that the autumn rise in ACTH is more dramatic in horses with PPID, so much so that the fall is actually a great time to test them. There are now seasonal reference ranges available to help distinguish horses with PPID from normal horses based on time of year testing is performed. The Equine Endocrinology Group’s 2019 Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction identifies fall months as mid-July through mid-November for purposes of PPID testing.”

Outside of fall, Schneider says ACTH testing might not pick up a horse with early PPID, as baseline ACTH might be normal despite PPID status. To increase the likelihood of a correct diagnosis, your veterinarian might perform a TRH (thyrotropin-releasing hormone) stimulation test in the nonfall months (mid-November through mid-July). This is a dynamic diagnostic test for PPID. The veterinarian takes a blood sample for ACTH before giving synthetic TRH and, again, 10 minutes later to see if ACTH rises significantly. We don’t yet have precise ACTH values from TRH stimulation in the fall months, she notes.

7. Consult your farrier about hoof care

Each fall assess your horse’s workload and environment. Helbig says while horseshoes provide hooves support, protection, and traction, the need in each situation differs.

Many horse owners pull their horses’ shoes for the winter. “Shoes cause drag on the musculoskeletal system, interfere with traction on slippery ground, and often get packed with treacherous snowballs,” says Helbig. “Some feel that barefoot provides a more natural lifestyle. It is also easier to monitor horses in winter if not worrying about pulled or shifted shoes in turnout. Be cognizant that barefoot hooves may be prone to bruising,” though one alternative is to boot your barefoot horse when you ride.

Old nail holes in barefoot horses also tend to split and chip, says Helbig, “wearing the hoof down without much to attach a shoe to in the spring.” She adds that seasonal hoof care works best if you, your veterinarian, and your farrier collaborate to make decisions for your horse based on the climate and terrain you’ll encounter or ride on in winter.

8. Manage pastures and manure

Consider seeding pastures in autumn, before winter snow falls upon them. “Seeding is best accomplished when temperatures are above 60 degrees,” says Helbig. “Allow germination over four to six weeks (if weather is conducive to it) before putting horses back on the pasture. Rotational turnout pastures are important to allow a pasture to rest. Dividing a pasture is another way to allow turnout while one section at a time can rest.”

She also suggests spreading compost in the pasture before the ground freezes.

Take-Home Message

Like the industrious ant showed the lazy grasshopper in Aesop’s Fables, hard work and preparation are key to efficiency and success come winter. Working through a fall checklist will not only keep your herd as healthy as possible but also ease caretaking of your horses and farm during inclement weather.

Written by:

Nancy S. Loving, DVM

Related Articles

Stay on top of the most recent Horse Health news with