Equine Laminitis: Turning Over New Leaves

A research update on preventing and managing acute laminitis cases

It took thousands of years for Mother Nature to design the equine foot—a strong, sturdy structure capable of carrying 1,000-pound animals over miles of hard, rugged terrain at a walk, trot, or gallop for decades of life. Widely viewed as an architectural masterpiece in terms of anatomy, the equine foot and its function truly are miraculous … yet at the same time disastrous.

It really is no wonder so many horses founder. Their entire body weight is essentially suspended inside the hoof capsule by microscopic interdigitating fingerlike projections of tissue called lamellae or laminae. Lamellae on the hoof’s inner wall connect with the lamellae on the outer aspect of the coffin bone (the third phalanx) to carry that bone—and, therefore, the entire horse’s weight—within the confines of the hoof.

When working well, those laminae are like Fort Knox, protecting healthy horse feet. If the lamellae become inflamed, they become weak and unable to perform their task. As a result, the coffin bone begins to follow the laws of gravity, sinking toward the ground, with all the other bones in the limb in hot pursuit.

In fact, the nickname “coffin bone” might be apt because any lamellar inflammation compromising the hoof-bone connection can place the horse’s life at risk.

“The term laminitis accurately refers to inflammation of the laminae yet does not truly capture how devastating this disease actually is,” says James Orsini, DVM, Dipl. ACVS, associate professor of sugery and former director of the Laminitis Institute at the University of Pennsylvania’s (Penn Vet’s) New Bolton Center, in Kennett Square.

To improve our understanding of this complex disease, researchers and veterinarians around the world strive to learn more about the lamellae and have made scientific advances in laminitis diagnosis, treatment, and prevention over the past several years. In this article we’ll describe some of these and how dedicated research teams endeavor to not just battle but conquer laminitis.

Three “Types” of Laminitis

Inflammation of the digital lamellae can stem from multiple causes. It can be:

1. Endocrine-related, occurring secondary to equine metabolic syndrome and pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID, equine Cushing’s disease).

2. Sepsis-related, developing following a systemic illness such as colitis (inflammation of the colon), metritis (inflammation of the uterus), pneumonia, grain overload, etc.

3. Supporting-limb-laminitis-related, developing after a musculoskeletal injury in the contralateral (opposing) limb, causing the horse to preferentially bear excessive weight on the sound limb.

Endocrine-associated laminitis, the most common form practitioners encounter today, comes and goes rather insidiously, often going unnoticed by owners.

In contrast to these chronic laminitis cases, acute (sudden-onset) sepsis-related and supporting-limb laminitis are usually unmistakable.

“Classic signs of acute laminitis caused by sepsis, or more rarely supporting-limb laminitis, include an increased heart rate, warmth in the affected feet, increased or even bounding digital pulses, and reluctance to pick up a foot due to the pain of extra weight-bearing on the opposite limb,” says Andrew van Eps, BVSc, PhD, MACVSc, Dipl. ACVIM, an associate professor of equine musculoskeletal research at Penn Vet.

Recognizing laminitis early, regardless of its cause, is key to managing it successfully, as highlighted in a 2017 study by Pollard et al. “That study … reported that almost half of examined horses ultimately diagnosed with laminitis went unrecognized by the owner,” says Orsini. “Instead, owners believed the horse was simply lame, had a foot abscess, was colicky, or just stiff.”

In cases of systemic infection, however, you have some warning; don’t wait for signs of acute laminitis to develop, says van Eps. In “any horse with colitis, metritis, pneumonia, or other conditions potentially resulting in sepsis, where bacteria and toxins produced by bacteria enter the bloodstream, one must always be very wary of ensuing laminitis.”

This gives owners and veterinarians a very small window of opportunity during which to act. Unfortunately, no “cure” for acute laminitis currently exists. Instead, veterinarians treat the underlying disease while trying to maintain lamellar integrity using the following strategies.

Dr. James Orsini

Preventing Acute Laminitis in Sick Horses

When veterinarians are trying to treat an initial disease process, they must also protect the feet. One of the most effective ways to prevent acute laminitis in sick horses is with cryotherapy, also known as continuous digital hypothermia.

“All horses with a systemic infection and risk of sepsis should be (treated with) cryotherapy to help prevent laminitis before clinical signs develop,” says van Eps, adding that this approach can limit laminitis progression even after the horse shows signs of lameness.

“Cryotherapy involves cooling the equine foot and distal (lower) limb to maintain a hoof temperature below 10°C (50°F),” Orsini says, a temperature established from hoof surface and probe temperature studies. “Cooling should be initiated as soon as the horse is identified as at risk of developing laminitis until 24 hours after resolution of the clinical signs of the underlying systemic disease. Icing may be needed for several days straight in horses at greatest risk and clinically the sickest.

“Dr. van Eps and I are currently collaborating on a couple of projects to better understand the effects of cooling on the various layers of the hoof, such as the hoof wall and lamellar tissues,” he adds. “With this information we will be better able to cool the lamellar tissue to our target temperature of <10°C.”

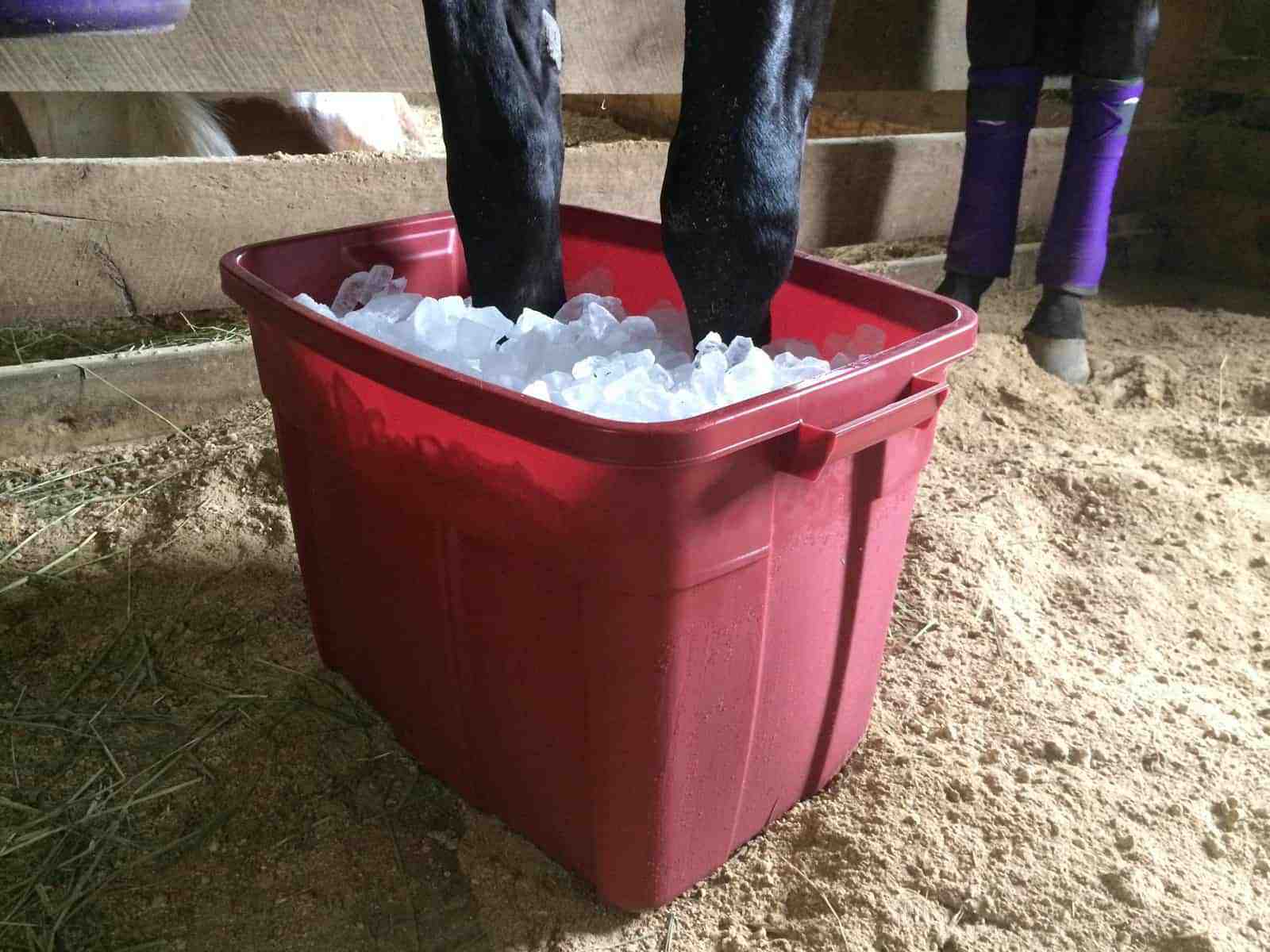

Various methods exist for providing cryotherapy, such as ice-immersion (i.e., in a bucket) and commercially available compression boots, the latter of which Orsini says are often price-prohibitive.

“Anyone who has participated in managing laminitis with cryotherapy knows this is a highly labor-intensive task,” says van Eps. “Although there are some boot solutions out there, they still require frequent restocking with ice, and the tolerance for boots differs between horses. Although achievable in hospital environments with staff and the right equipment, it is currently difficult to practically perform at home.”

Indeed, this therapy can be labor-intensive, but its positive outcomes are undeniable. In a study published in January, van Eps and colleagues found that cryotherapy (in this case, placing the limb in a rubber boot filled with ice slurry to the top of the cannon bone) does, indeed, reduce inflammation in the lamellae. They noted a decrease in various inflammatory mediators and white blood cells in the lamellae of cryotherapy-treated feet after experimentally inducing laminitis.

Anecdotally, concerns veterinarians have regarding cryotherapy include the development of skin infections (cellulitis), softening of the hoof wall, and local tissue necrosis (death), presumably due to the lower limb’s prolonged exposure to cold water. To abrogate these potential side effects, Orsini and colleagues recently studied and reported on a novel “dry” cryotherapy system for preventing laminitis.

“This commercially available system uses a boot that houses malleable cryotherapy packs that conform to the hoof and pastern to cool the distal limb more effectively,” Orsini says. “Our data show that this unit can cool the hoof wall to 11°C (52°F) even in warm, ambient temperatures and that median hoof wall temperatures as low as 6.75°C (44°F) could be achieved.”

These cryotherapy packs require frequent changing (every two hours), making the process still relatively time-consuming, but economical, practical, and safe, he says.

Current Treatment Options

If the owner and veterinarian do not identify a systemic illness and begin treatment quickly enough, laminitis can set in. In these cases, treatment rather than prevention becomes the goal and is, unfortunately, a losing battle in all-too-many instances.

Available data regarding outcomes are sparse, but Louisiana State University researcher Britta Leise, DVM, PhD, recently reported that only 25% of laminitic horses become sound, 25% remain lame, and 50% don’t survive long-term.

In general, owners and veterinarians can follow these four strategies to help horses suffering from acute laminitis:

- Apply cryotherapy to limit disease progression;

- Provide pain relief, primarily via non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which also reduce inflammation;

- Restrict the horse’s movement via stall rest; and

- Pursue orthotic/corrective shoeing or use sand as bedding because it conforms to and supports the sole and frog.

Other “treatments” exist but with far less evidence supporting their use and unknown to variable success.

In severe cases some veterinarians recommend severing the deep digital flexor tendon (which runs down the back of the limb and inserts into the coffin bone) or the inferior check ligament attached to it. This reduces the tension placed on the bottom of the bone, with the goal of halting coffin bone rotation (forward and down) and preventing its tip from penetrating the sole. Veterinarians have also performed acupuncture and other alternative strategies in attempts to save affected horses’ lives.

However, “there is little evidence supporting any of these latter treatment options, and treatment should instead focus on the four strategies listed above,” says van Eps.

Managing Pain: An Elusive Task

Despite the variety of pain-managing medications available, such as local anesthetics, NSAIDs, and opioids, these drugs frequently fail to provide sufficient relief for horses with acute laminitis. As you can imagine, having a bone slowly slip through the bottom of your sole causes unbearable pain.

“Pain management continues to pose a major road block in conquering laminitis,” says Orsini.

One reason for this failure of relief is that the lamellae do not have a direct blood supply. They obtain nutrients and oxygen via diffusion across tissue membranes. In addition, multiple shunts between the veins and arteries of the feet, called arteriovenous shunts, can divert medications administered systemically away from the lamellae.

“Ultimately, uncontrolled pain usually is the reason owners elect humane euthanasia for laminitis horses,” says van Eps.

Accurately assessing pain continues to pose challenges and welfare issues in laminitic horses. European researchers (Dalla Costa et al., 2016) used the “Horse Grimace Scale” (TheHorse.com/148489) to gather information on the pain level a horse experiences during acute laminitis. This facial-expression-based pain coding system evaluates ear and mouth position, tightening/tension around the eyes, strained nostrils, etc. The traditional method of assessing laminitis pain—the Obel grading system—involved moving a horse. The grimace scale avoids the need to make painful horses walk and appears to be a potentially effective method for assessing acutely laminitic horses’ pain, the team reported.

“NSAIDs remain the mainstay for pain management for acute laminitis,” says van Eps. “However, we are realizing the importance of using multimodal therapy, which involves using multiple drugs acting by different pathways, to provide better analgesia with less side effects.”

Other options for pain control include:

- Drugs such as intravenous lidocaine to help control pain in severe acute cases;

- Opioid drugs, such as butorphanol or morphine, or other medications, such as gabapentin, designed to interrupt “central” pain pathways, particularly if used early in acute cases in combination with NSAIDs; and

- Regional techniques such as epidural or continuous regional nerve blocks to help control pain in severe cases.

- “Cryotherapy also provides analgesia in cases of acute laminitis,” van Eps adds.

Novel pain management approaches currently in various phases of development and not yet clinically available might offer owners of laminitic horses hope. For example, as van Eps described in a 2015 study, pain medications can be bound to nanoparticles that, after intravenous injection into the bloodstream, localize to areas of inflammation, such as the lamellae during laminitis, to provide pain relief.

Take-Home Message

The acute laminitis that can develop in horses with systemic illness or catastrophic injuries is often more devastating than the inciting illness or injury itself. Therefore, prevention is key to survival, and cryotherapy remains an important tool on this front.

Neither a cure for laminitis nor a foolproof treatment regimen exists, and uncontrollable pain commonly contributes to an owner’s decision to euthanize an affected horse. Research efforts are ongoing to improve pain management and identify new ways to prevent laminitis.

Written by:

Stacey Oke, DVM, MSc

Related Articles

Stay on top of the most recent Horse Health news with